IN FOCUS: Missing people in Singapore and their loved ones who haven't stopped searching

When someone goes missing, the goal is closure. But what happens when it has been decades with no answer in sight? CNA speaks to individuals who continue to hope, and a non-profit group that traces missing people.

A woman carrying a placard with the photo of Chinese national Han Yanfei, who went missing in Singapore on Nov 8, 2009. She hasn't been found. (Photo: Crime Library Singapore)

SINGAPORE: Two years after Lim Boon Hua slipped out to buy breakfast and never returned home, his younger brother, Jeffrey Lim, spotted someone who looked just like him.

“My heart beat so fast. I (was) almost mistaken (he) is my brother,” Mr Lim told CNA.

He felt happy at first, then angry. "I wanted to ask him, ‘Why so long never contact?’ But no, it’s somebody else. The way he dress, his style. Same kind,” he said.

Mr Lim’s elder brother was 32 when he went missing in December 2003. He had left home with just a wallet and house keys. He didn’t own a mobile phone.

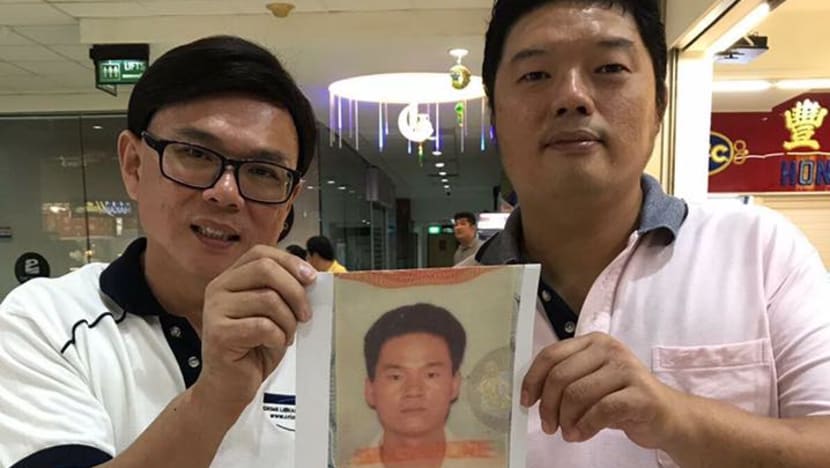

Almost two decades later, Mr Lim, now 48, still hasn’t heard from his brother. But with the help of Crime Library Singapore - a non-profit group that helps to trace missing people - he remains hopeful that his big brother will turn up one day.

Mr Lim’s case is just one of the roughly 1,000 cases on Crime Library's books. But its 55-year-old founder Joseph Tan isn’t giving up.

TO FIND A MISSING PERSON

Crime Library's approach has developed over the years.

In the past, Mr Tan would rely on its volunteers to print and disseminate flyers by hand. For some people, even with their identity card number, “it’s never been easy to trace”, he told CNA.

For instance, there may be people who go missing because they owe money to loan sharks, but these cases wouldn’t be publicised as help-seekers wouldn’t want to be seen to be associated with loan sharks. So Crime Library would work with anti-loan shark associations.

“Help-seekers” refer to the people who approach Crime Library to open a case.

With social media now, the search process has become more efficient. Crime Library needs the missing person’s photograph, and as much detail as possible about their social media accounts.

Mr Tan pointed out that publicising the missing person’s face might be effective because of “public shaming”, especially for youths. He may, for instance, first try sending a text message to the missing person to “warn” them.

“If you do not want this to happen, please report your safety. If you do that, we don’t need to go to the extreme to publicise your face,” he said, describing an example of a message he may send.

But even with posters, “with today’s mask-wearing situation, it can still be very hard to recognise someone”, Mr Tan noted.

With regular reports of young people who go temporarily missing, Mr Tan admitted he doesn’t have a “foolproof solution” to address the problem. But he believes there should be legislation to make it illegal for people to house young runaways.

“As a victim support centre, we’ve dealt with a lot of distressed families. A lot of parents agreed with us to propose a law to stop giving shelter to the missing people,” he said.

“(If you want to shelter someone), it’s your duty to make sure the parents of the delinquents or teenagers know their whereabouts. … You must do your part and make sure that the person you’re sheltering hasn’t been reported missing.”

What remains unchanged in his search process, with or without social media, is that an official police report must be made to show that the police are aware about the missing person, Mr Tan added.

There is “no minimum time required for the missing person to have lost contact with family members before the report can be lodged”, said the Singapore Police Force (SPF).

After a missing person report is received, the police will commence investigations.

“These include interviews with those who may have information on the whereabouts of the missing person; checking with institutions such as the Immigration & Checkpoints Authority and hospitals for travel and admission records; canvassing information from available closed-circuit television footage to determine the missing person’s possible movement; issuing appeals for information via the mainstream media as well as posting them on social media platforms; and issuing a police gazette for officers on the ground to look out for the missing person,” added SPF.

“The police gazette will remain in force until the missing person has been found.”

Using social media allows the police an additional channel to reach out to the public. With the ease of sharing content on social media, this provides “a multiplier effect” to police’s efforts to find the missing person.

More often than not, the missing person is located.

NUMBER OF MISSING PERSONS BELOW 16 YEARS OLD

From 2018 to 2020, the number of persons reported missing below the age of 16 has decreased, said the Singapore Police Force (SPF).

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| No. Persons Missing | 450 | 386 | 287 |

REUNITING FAMILIES

A bulk of Crime Library’s cases today involve looking for long-lost biological family members, such as Mr Lim’s brother.

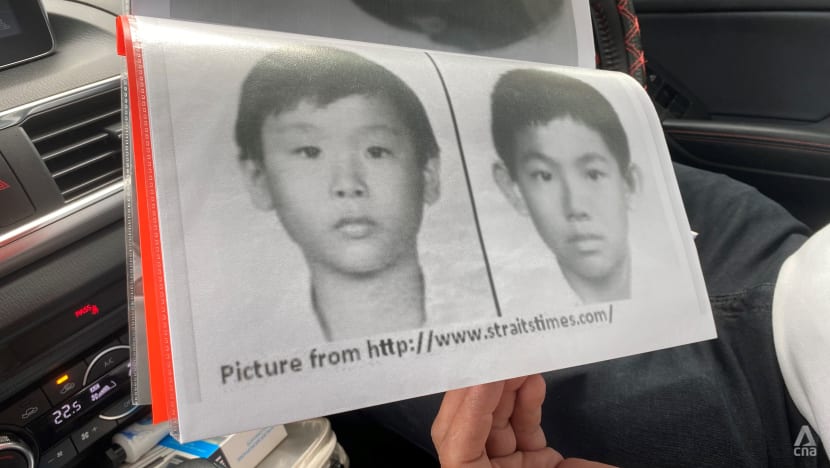

In 2021, Crime Library successfully arranged a reunion between a mother and daughter that was 42 years in the making, which was covered by the Straits Times. The daughter had been given up for adoption, and only reached out to Mr Tan after her husband read about another reunion which Crime Library had arranged.

“We cannot turn people down because they have no one to turn to. But I didn’t say we’re very good. We’ve only closed over 500 family cases; I still have over 1,000 help-seekers still waiting for closure,” said Mr Tan.

Since the “circuit breaker” period in 2020, cases have started to pick up. And 2021 is a “very busy” year too, with Crime Library receiving about 30 to 50 cases per month.

Mr Tan attributes this to “a timing thing” due to personal reflection about one's life brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. People may be prompted to seek answers.

But while photos of happy reunions plaster Mr Tan’s wall in his home office, he is aware that not all reunions may be happy, such as in divorce cases. His job is to ensure nobody gets hurt due to the sudden appearance of a long-lost family member.

“Help-seekers want to find their kin, but we also have protocol. We want to ensure nobody is hurt. We do the middleman thing. Sometimes we talk to the son or daughter, and supposing the ex-wife is still alive, we don’t want to hurt the ex-wife,” he said.

“Yes, reunion means one part is happy, but the other part might not be good. They might think, ‘Hey I divorce already. Why he suddenly appear?’ So we have to make sure it’s a happy reunion. If it’s not going to be a happy reunion, we will not allow it.”

Such instances may include when a former spouse doesn’t want the estranged parent to meet their children, or when an adopted child’s biological mother hasn’t told her current family about the child she gave up for adoption.

In such cases, allowing a reunion may “destroy” the other party’s current life, said Mr Tan.

Nonetheless, he would still help the help-seeker have “a quiet kind of reunion” by “quietly taking a photo” of the other party, to show the help-seeker that their loved one is happy.

UNSOLVED MURDERS

While much of Crime Library's time is spent trying to locate missing people, in its infancy it often looked at cases involving murders.

After all, the group was started because Mr Tan knows firsthand how it feels to suffer such tragedy.

He set up the volunteer-run group in 2000, four years after his cousin was kidnapped and shot in Manila. Even though the kidnappers were eventually nabbed, his family was devastated.

“Although it didn’t happen in Singapore, the feelings, the aftermath, the sadness are all the same. … So my family felt that we should start something on an education basis for crime awareness,” he said.

“A lot of those rape and murder cases are very sad cases, and normally, families don’t want to sensationalise the cases. One or two reports and that’s it, full stop. Which means people are not reminded not to let their child out of their sight.”

With several factors in play - such as Mr Tan’s cousin’s murder, his former job as a police officer, and the support from fellow victim-of-crime families to set up a platform that reminds parents to keep their child safe - it was a no-brainer to start a website for Crime Library during the dot-com boom.

“You feel that you can do something. I didn’t join the police force just to do a job; I hope we can do something for society,” he said.

In Crime Library’s heyday, it was involved in the Huang Na murder case that gripped the nation in 2004.

The group helped to search for the eight-year-old girl’s murderer by giving out missing person leaflets and setting up a website to gather tip-offs. The murderer eventually surrendered to police in Penang, Malaysia, where he had fled, and was brought back to Singapore.

With its public profile raised by the Huang Na case, Crime Library decided to “openly help all victims of crime”, said Mr Tan.

While in the police force, Mr Tan also saw the benefit of speaking to people in the neighbourhood when the Neighbourhood Police Post (NPP) system was introduced in the 1980s and he was posted to various departments.

“I thought the NPP system was very good because you get to visit everyone. It’s like a kampung head. You get to know everybody. You do house visits,” he said.

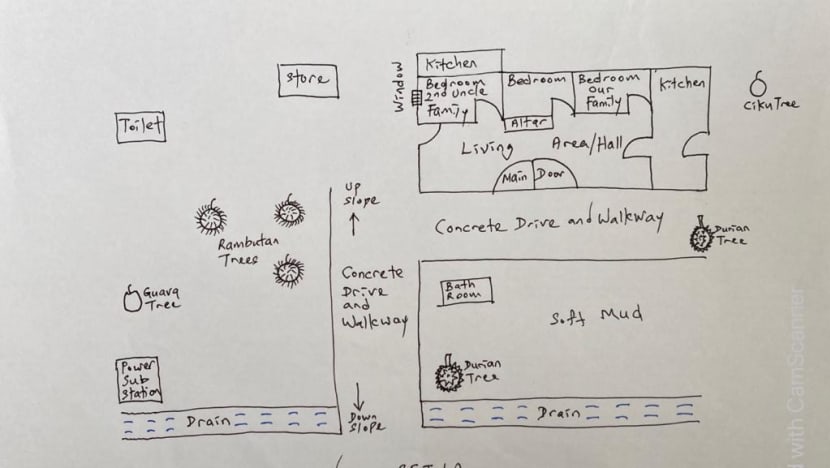

Building rapport on the ground came in handy when Crime Library did a crime awareness tour around Geylang Bahru in April 2021. They were approached by an old neighbour of the four children who were murdered in their Geylang Bahru flat in 1979 with new information about the infamous unsolved case.

To date, the murderer hasn’t been found.

“If you follow up on our Facebook, (you’ll see that) we go and visit one by one … the old neighbours. We hope we can help the police to solve the case,” said Mr Tan.

He added that the mother of the four children is getting old, so he hopes to help provide closure for her.

Such closure is also something Goh Leng Hai has been seeking since his sister was raped and murdered in 1980.

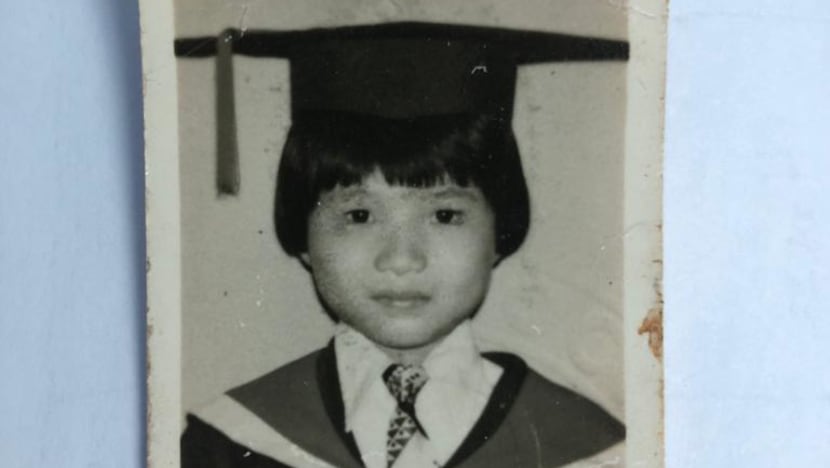

His sister, Goh Beng Choo, was eight when her dead body was found in a bush behind a Chinese temple near her house off Jurong Road. The culprit has not been caught.

Now 52, Mr Goh has been on the hunt for the killer for more than 40 years.

“The case is still an open case. All along I was trying to find out how to open up this case, because my parents are already very old. And I wanted to put a closure (to this incident),” he said.

Around the end of 2020, a 13-year cold case involving missing teenager Felicia Teo made headlines when two men were accused of murdering her in 2007. Shortly after, Mr Goh saw a Facebook post from Crime Library about the work they do.

Inspired to take action, he reached out to Mr Tan.

This time, Mr Goh had social media and a media interview to help his appeal for new information regarding his sister’s murder.

With “new technology and resources” available to the police, he hopes the case can eventually be solved.

Even though Mr Goh said his parents are “unsure” about the final outcome of reopening the case, he and his other three siblings are adamant that they continue searching for their late sister’s killer for closure.

“We did have a very special feeling among our siblings, where we dream of incidents about this case. We feel that the hope is still there and the killer is still alive,” he added.

LOCKED IN LIMBO

While individuals like Mr Goh aren't searching for a missing loved one, their sense of “ambiguous loss” might mirror those in such a situation.

“Ambiguous loss is defined as the type of loss that remains uncertain. This type of loss is ongoing with no closure,” explained Shivasangarey Kanthasamy, a senior clinical psychologist with the Institute of Mental Health’s Department of Psychology.

“Physical ambiguous loss is when the individual that is being missed is physically absent and there is no certainty about their status or situation (i.e. a lack of psychological presence).”

When a loved one goes missing, they essentially “leave without goodbye”, added Ms Kanthasamy.

“The ambiguity about the situation does not allow the change or resolution to take place and it can get more complicated. The psychological struggles may include prolonged intense feelings of being ‘stuck’, helplessness, possible guilt and sadness.”

If such grief remains unaddressed, it can lead to "perceived stress".

“The impact depends on each individual’s coping strategies, social support and belief system. Those with limited or lack of resources may experience high perceived stress,” said Ms Kanthasamy.

Counsellors can help the individual “understand what the particular situation means to them with the intention to discover hope”, she added.

“Finding meaning and discovering hope is important to move on with ambiguity. Then, counsellors can review the concept of how their client can let go of things that are not within their control.”

But reality is less straightforward. Mr Tan said some families of missing people “find it very difficult to come to terms with life”.

When they see Mr Tan and his team come to visit, they often ask, “Wah, got people still care ah?”

“They’re so happy when they see us. I feel that we don’t want to correct them because (we want to) give them some hope,” said Mr Tan.

As for Mr Lim, his hopes for a reunion with his older brother are kept going by a single success story he once heard about a man who found his missing sister in an old folks’ home after eight years.

Even so, life must go on, which means “slowly accepting that it’s no more” and making peace with the situation, he said.

These days, Mr Lim’s memories of his brother only come occasionally: On his brother's birthday, when he listens to certain music, or when he eats char kway teow. He also thinks of his brother's tidiness whenever he clears his messy cabinet.

And sometimes, when he sees two boys playing together, he’d think: “I used to be like that.”

Members of the public who wish to provide information arising from a missing person appeal can call the police at 1800-255-0000 or submit information online at www.police.gov.sg/iwitness. All information received will be kept strictly confidential.

Crime Library can be contacted at 6293-5250.