‘Words just can't come out’: The challenges of living with a stutter

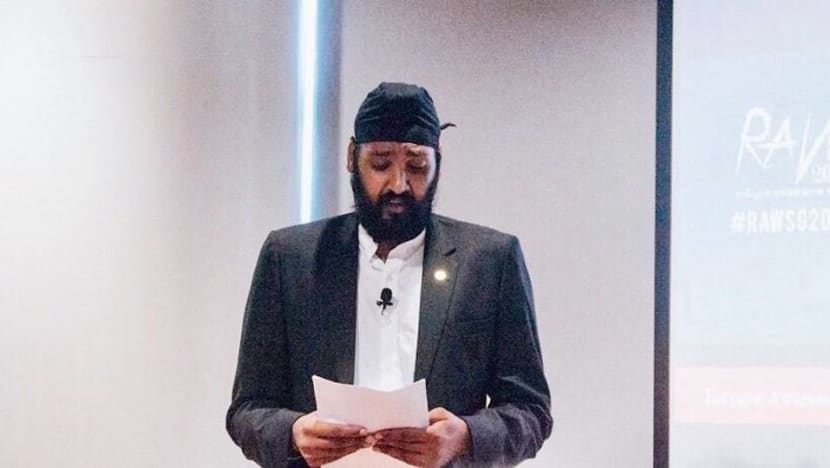

Mr Nawaljeet Singh moderating a panel discussion. (Photo: Facebook/Refugee Awareness Week)

SINGAPORE: Mr Nawaljeet Singh was about 14 years old when he became aware of his stutter.

“I was speaking to a friend and I realised I couldn’t get the words out,” he said.

The senior analyst laughed as he remembered the expectant look on his friend’s face as Mr Singh struggled to finish his sentence.

Now 30, Mr Singh says he has come across different reactions whenever he finds himself tripping on words during a conversation.

In one incident, a concerned university classmate had patted him on the back and assured him: “It’s fine.”

But with his close friends, Mr Singh good-humouredly pointed out that they would never fail to give him a hard time with their playful jibes.

“I think on the one hand, you want a bunch of loving and caring friends, (but) on the other hand you also want friends that normalise this as well,” he said.

PERFECTLY NORMAL PEOPLE WITH NORMAL IDEAS

Mr Singh is among the 1 per cent of adults worldwide who suffer from a stutter.

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder which commonly appears in 5 per cent of children at the ages of two to five. If not dealt with early on, it can continue past childhood.

Studies have shown that people who stutter may experience negative assumptions by other people about their intelligence, personality or competence, said Dr Elysia Soh, a speech therapist at Sengkang General Hospital.

They are judged as having poor speaking abilities compared to others, and therefore they are seen as being deficient other ways, Dr Soh said, adding that such views do not hold any truth.

“Stuttering is a disorder of speech production. It is not a language disorder, and not a disorder resulting from any emotional or mental conditions,” she stressed.

Dr Valerie Lim, founder of private clinic Planting Speech, echoed similar views: “They are perfectly normal people with normal ideas, normal thoughts.”

However, they are not able to programme their muscles to get the words to come out smoothly, Dr Lim explained.

One of Dr Lim’s patients described the feeling of having a stutter as similar to a blocked tap.

“Water is trying to flow out but it can't because of some blockages,” he told her. “Likewise, I know what to say but the words just can't come out."

When a doctor once asked Mr Singh if he had trouble forming the words in his head, his response was: “If it’s getting stuck anywhere, it’s right at the tip of my tongue.”

Mr Singh, whose speech dysfluency only crops up during longer conversations, said what helps him power through a stutter is if he has a good understanding of the topic of conversation at hand.

“For every word that I need to say, if … I can’t get it out, I will find a substitute for it,” said Mr Singh.

DAILY TASKS CAN BE A CHALLENGE

While the severity of dysfluency varies from person to person, everyday tasks can be particularly stressful situations for those who stutter.

Dr Lim said she has come across patients who would order juice from a drink stall instead of Coca Cola because it would be too difficult to enunciate the latter.

They would tell her: “I had to order juice again because I couldn't get the word Coca Cola out, and I don’t even like juice.”

Another patient, who had a moderately severe stutter, even changed his name because he could not pronounce it fluently.

Dr Lim added: “Quite a few of my clients have chosen to do more back end kind of jobs … Some of them will say: ‘Actually if I have it my way, I would love to be a lawyer or a teacher’.”

Avoidance behaviours such as this can be the most “handicapping” aspect of the speech disorder, noted Dr Soh, as it may lead to reduced social and occupational participation.

This may eventually result in feelings of loss of control, decreased mood and increased anxiety.

Mr Benjamin Seet, a graduate student, acknowledged that his stutter does become a bit of a challenge during phone calls.

“There’s always this anxiety that the person on the phone would not able to hear me well,” said Mr Seet, adding that this would make him constantly second guess himself.

Whenever he felt like his words were “stuck” during phone calls, he would speak slower to make sure his point would come across as clearly as possible.

CONTENT OF SPEECH MORE IMPORTANT, NOT DELIVERY

Despite the obvious communication challenges, Mr Seet is confident that his stutter has not hampered his career ambitions of becoming a teacher.

“I have been very fortunate that those who I have worked with … they would always care more of what I’m saying and not how I’m saying it,” said the 30-year-old, who previously worked as a teaching assistant in the National University of Singapore.

Mr Singh also agreed that people are usually “almost always more concerned with the content of my presentation than the delivery".

While Mr Singh has had doubts about how his stutter affects his work, he admitted that his worries have not been significant enough to make a tangible impact on his career.

In his previous job at a social enterprise, Mr Singh was tasked to give a weekly briefing for a project.

“I did that briefing almost continuously, almost always cognisant of my speech impediment,” he said.

“It’s not like I don’t trip on my words … But, it’s okay,” he shrugged.

Offering advice on how one should interact during a conversation with a person who stutters, Dr Soh said it was important to let them complete their sentences.

“As a conversation partner, you may feel uncomfortable with periods of silences that can occur when a person who stutters has a block, or with repeated syllables and sounds,” said Dr Soh.

“However, if you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter," she added. "Dysfluent speech is simply another person’s way of talking to express themselves”.

Dr Soh added that there is also no need for “advice” such as telling people who stutter to “slow down” or “relax”.

While it might be well-meaning, it could also be more disruptive to the conversation.