CNA Explains: The rise of image-based sexual abuse in Singapore, and its impact

How bad is the situation and how can victims be better supported? CNA’s Chan Eu Imm takes a closer look.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Every time she closes her eyes, she’s haunted by the thought that someone, somewhere has a topless photo of her – a photo which isn’t hers and which she never took, much less shared with others.

Michelle* was just 14 when a picture of her in a tank top was manipulated into an image of her bare-chested, and then circulated online.

“Every day felt like hell” when she went to school, where it seemed like "everybody was staring at me and talking behind my back”. She felt like an “embarrassment” to her family, and worried they might kick her out of the house.

“I wanted to prove that it's not me, but how … and who will trust me?” she said. “(I) had no experience in such things, I was helpless.”

Stories like hers are becoming increasingly common, and anyone can be a target.

A Singapore government survey in April found a rise in harmful content encountered on social media platforms. Cyberbullying and sexual content were the most common types – and in the latter category is the phenomenon of image-based sexual abuse.

What is image-based sexual abuse?

It's the creation, acquisition, extortion and distribution of sexual images or videos of someone, without their consent. Even threatening to do any of this is considered IBSA.

Some instances include video voyeurism, upskirt videos, deepfake porn, revenge porn and sextortion.

Who gets targeted?

“Women are more at risk mainly because they are seen, objectified as the fair, pretty, attractive gender … and now with social media, it's even more easy to project and amplify their presence,” said Associate Professor Razwana Begum, who heads the public safety and security programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

“We tend to see more influencers who are female … When they start sharing their images for the ‘likes’ … they tend to be sometimes manipulated by bad actors.”

Children are also easy targets for what Dr Chew Han Ei, adjunct senior research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies think-tank, called “the most egregious form” of IBSA – where victims are young and crime syndicates capitalise on new technologies to profiteer.

When it comes to men, IBSA often takes the form of blackmail and extortion. Here, crime syndicates impersonate women or even teenage girls, to get men to strip or be in the nude before taking photos and beginning the extortion process, said Dr Chew.

How worrying is the situation?

In August, Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said in a written parliamentary reply that an average of about 340 cases were reported to the police each year between 2021 and 2023, involving the possession or distribution of voyeuristic, intimate or abusive images.

He added that the police does not track the number of such cases involving deepfakes or manipulated images or videos using generative artificial intelligence tools.

But in the first half of 2024, voyeurism cases in Singapore climbed about 12 per cent from a year ago. These offences generally involve observing or recording someone in a private act, without their permission.

It’s not just about numbers when it comes to IBSA, said Dr Chew, who researches social issues with a focus on technology adoption.

“Cybercrimes such as scams are more numerous and it affects more Singaporeans,” he said. “But that doesn't mean that we should not be concerned about (IBSA), because when we look at the victims; when we look at the experiences of the survivors, it is definitely more intense than losing S$1,000 to a scammer.”

“They sometimes have suicidal thoughts or self-harm … they fear for their own safety when they have to transact or they interact online,” added Dr Chew.

Michelle, now 21, said that while she knew she was not at fault for a photo that wasn't even real to begin with, she also felt like she was guilty for "not dressing modestly" or even wearing a tank top.

She had to remind herself that the blame lies with the perpetrators who edited the photo – or photos. “I'm not sure … were there any other copies of it? Perhaps there's a copy of me being fully naked, who knows?”

She sought psychiatric help for post-traumatic stress disorder, and it took about two years before she spoke out about the incident.

How have tech advances made things worse?

Adding to the complexity of IBSA cases is the growing ubiquity and sophistication of generative AI.

More than 95 per cent of AI-generated deepfake porn targets women.

The rise of such new technologies in recent years has exacerbated the extent, frequency, type and severity of online harms, said Dr Chew, who’s also a board member of the SG Her Empowerment non-profit. “The problem is going to be worse.”

Then there are encrypted platforms like Telegram chat groups fuelling increased demand for IBSA-related content, while making it much harder to track and secure harmful sexual content for evidence.

“A person who's interested in such images could actually go online … and look for this information or these images, pay a small fee and not get detected at all,” said Assoc Prof Razwana.

Why aren’t more people calling out IBSA?

The April government survey, done by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information, also found that despite coming across more harmful content online, 60 per cent of respondents did nothing because they were either unconcerned or thought it wouldn't make a difference.

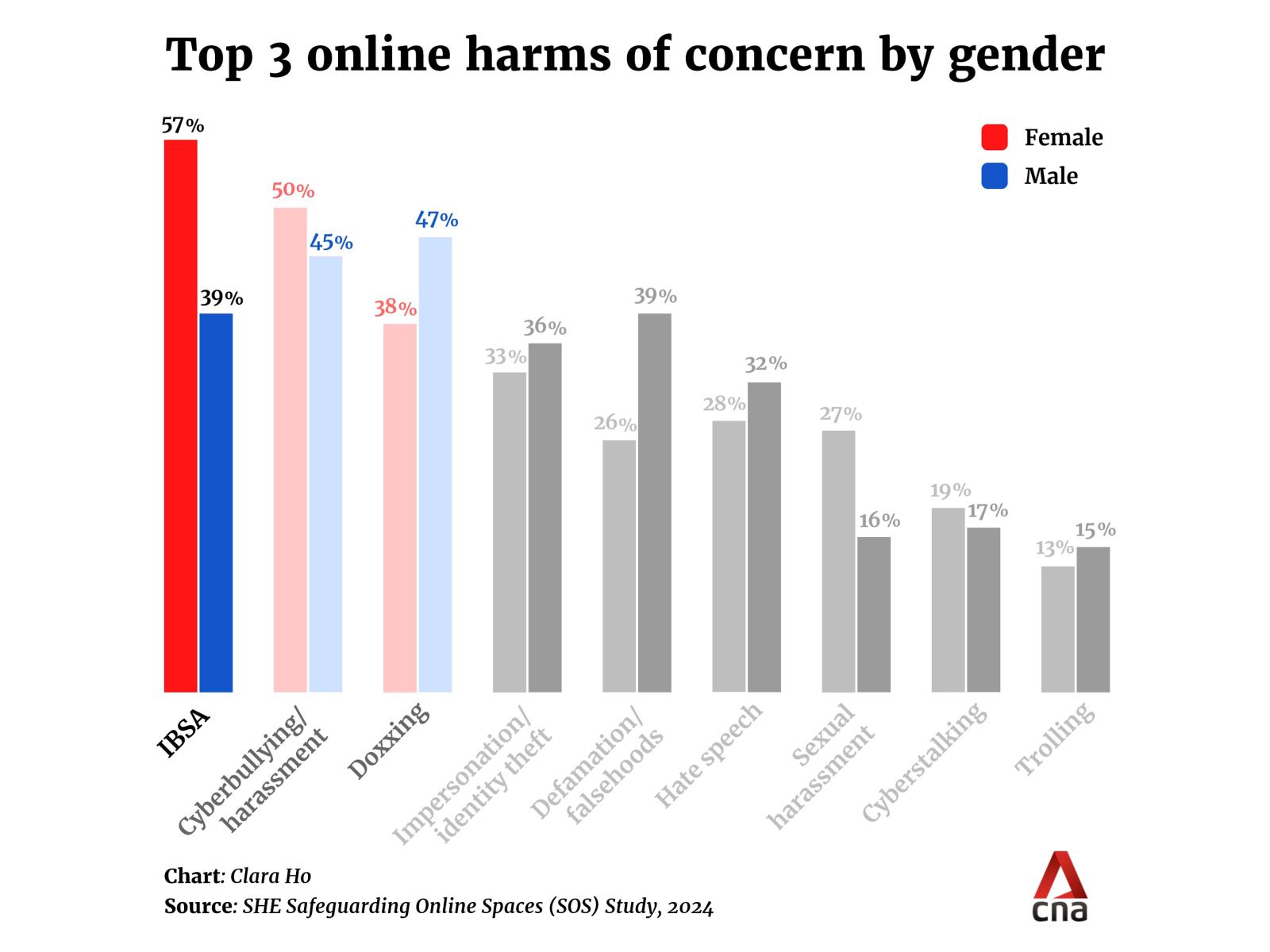

The same sentiment was seen in a separate survey done last year SG Her Empowerment.

A “very telling” statistic from this study was that one in five victims of online harms thought it’s a normal part of life, Dr Chew pointed out.

“It's a red flag, when the victims of the online harms think that it's okay … to perpetuate these crimes or to commit these crimes and also to encounter them,” he said. “It's a sign that our societal norms are changing and we definitely need to do more to make sure that we don't go further down this slippery slope.”

“It doesn't happen to everyone, and it shouldn't happen to everyone,” said Assoc Prof Razwana, who’s also a Nominated Member of Parliament.

She believes there’s also an element of desensitisation, due to cases of sexual violence regularly coming up in the news.

“However, I would think that when that situation happens to an individual, it's unlikely that you're going to be able to push it away,” she said.

How can victims be better supported?

Experts said those traumatised by digital sexual abuse need a safe space where they are free from judgment. Such a space could be provided by social service agencies or the police when handling such cases.

Dr Chew called for better public awareness of where to go for “one-stop” help and support.

Such a place would have counsellors to “walk the survivors through their journey”, and perhaps give legal advice, he added. Survivors might also need help to report to either the authorities or to platforms to take down the content.

Are current laws effective?

The six social media platforms designated by Singapore as having significant reach or impact - Facebook, HardwareZone, Instagram, TikTok, X and YouTube - must follow a legally binding Online Safety Code.

The Code requires them to curb the spread of harmful material such as sexual and violent content – by minimising exposure to users, making reporting as easy as possible and publishing yearly online reports.

To enforce this, an amended Online Safety Act took effect in February 2023, with new provisions to hold the social media platforms accountable if they don't comply.

A few months later, a new law – the Online Criminal Harms Act – was also passed, giving the government the power to order websites, apps and online accounts be taken down, if they're suspected of being used for criminal activities.

In other words, it's definitely illegal to threaten to or share intimate images or recordings without consent.

But experts pointed to challenges in how quickly technology is advancing, as well as the drawn-out process of reporting, charging, prosecuting and getting content taken down.

“Very often now the case is that you have to establish whether the upload or the sharing was consensual, and it can be complicated, (for example) because they were in a relationship when it was taken,” said Dr Chew.

“But why don't we just assume at the get-go that the content was non-consensual? (Then) we can take it down … then we sort out who was responsible, whether the right permissions were taken.”

To this end, the government at the start of October announced a new agency to more swiftly put a stop to online harms.

Instead of depending on the usual court-based process, victims can apply to this government agency, which will then go after perpetrators and online service providers.

In tandem, new legislation is also in the works, to allow victims to seek civil remedies from their perpetrators.

“There's too many bad guys out there in the world,” said Michelle, when asked to give advice to someone going through what she did.

“What we can do is to protect ourselves, and that's how it is. Try to move on … And please seek help.”

WHERE TO GET HELP

- Police

- Emergency: 999 (for immediate assistance)

- Emergency SMS: 70999 (for immediate assistance if it's not safe to talk)

- National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline

- 24-hour helpline: 1800-777-0000

- Samaritans of Singapore

- 24-hour hotline: 1767

- 24-hour caretext: 9151 1767

- Caremail: pat [at] sos.org.sg

- Institute of Mental Health

- 24-hour helpline: 6389 2222