'They don't realise they are victims': In family violence cases, hurdles are everywhere - but so is help

From 2020 to 2022, there was an increase in police reports related to offences commonly associated with family violence, such as hurt, criminal force, assault and criminal intimidation.

File photo depicting abuse. (Photo: iStock/PrathanChorruangsak)

SINGAPORE: As a social worker who has handled family violence cases, Ms Kristine Lam knows the significance of the initial interaction between victim and police.

It may, after all, determine whether the victim seeks help again.

“Police is usually one of the first touch points. And when we look at international literature, it does say that the first experience will cause the victim to make that decision whether or not to seek help again,” said the principal social worker for Care Corner Singapore. She was speaking to reporters during a briefing by the Singapore Police Force (SPF) on the rise of family violence cases on Monday (Oct 31).

“So if they have a very bad experience, then they may not trust the system.”

Drawing from personal anecdotes, Ms Lam recalled cases where the victim was asked many questions and nothing happened, or they felt that authorities doubted them and they didn’t know how to explain their situation. As a result, they decided not to continue seeking help.

Last January, Minister of State for Home Affairs Muhammad Faishal Ibrahim said that there was a 10 per cent rise in family violence cases every month between April and December in 2020.

He added that the increase was expected as people spent more time at home compared with pre-COVID-19 days.

Police said on Tuesday that the number of reports being filed for offences commonly associated with family violence, such as hurt, criminal force, assault and criminal intimidation, increased from 2020 to 2022.

The number of such reports went up from 2,560 in the first half of 2020, to 2,603 over the same period this year. The number of police reports filed for similar offences over the first six months of 2021 was 2,638.

The majority of the cases were spousal or ex-spousal violence, followed by parental violence and child violence.

Ms Lam believes that training police officers to handle such cases will “boost victims’ confidence to step forward for early intervention”.

TRAINING

In June 2021, the Police Training Workgroup was set up by SPF and the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) to provide frontline officers with enhanced training as certain knowledge and skills are required to handle a family violence case.

The workgroup comprises members from diverse backgrounds, such as family service centres, the Singapore Council of Women’s Organisations, crisis shelters and the Family Justice Courts.

“The nature of family violence cases is multifaceted and often rooted in complex underlying issues. As such, enforcement and prosecution may not always be the optimal solution to address the root cause of such violence,” said SPF in its media factsheet.

Explaining what frontline officers undergo during training, Senior Staff Sergeant Matthew Joshua Wee told reporters on Monday that training covers their “understanding of the psyche” – of the victims, as well as the perpetrators and vulnerable household members.

“These officers are required to also go through scenario-based training. They are reinforced with soft skills required to actually engage all these involved parties. … Soft skills include things like how we sit down, how we position ourselves when we converse with these victims,” he said.

SSS Wee, a crime prevention officer from the Bedok Police Division and a trainer in the workgroup, added that the workgroup adopts a “train the trainer” model, where a select group of officers undergo the training and then proceed to train other frontline police officers.

“Formerly, I was a community policing officer … and we have to communicate often with victims/survivors to understand their situation and assess how we can help them and engage their family members. … With this training, I feel that I can better identify those telltale signs of violence through a structured framework,” he said.

“It also offers victims/survivors the appropriate resources available, because all of our police officers will now be aware that all these resources are available for these victims/survivors to address their respective needs.”

ASSESSING FACTS, PROVIDING SUPPORT AS FRONTLINE OFFICERS

The family violence community policing officers are one such group of frontline officers undergoing such training.

Officers from the Community Policing Unit were appointed as family violence community policing officers across the police land divisions from July 2022.

Specialising in the management of family violence cases, these officers are the “main point of contact between the SSAs (social service agencies) and involved parties in the family to provide a more coordinated support network to the victims, and an efficient information-sharing process”, said SPF.

In recurring family violence cases, the parties involved are engaged by the same family violence community policing officer and family service centre counsellor to “build familiarity and trust”. This makes families feel more comfortable sharing and listening to advice, added Inspector Tony Thian, deputy officer-in-charge of the community policing unit at Rochor Neighbourhood Police Centre.

Once a family violence report is lodged, the police will first assess the facts and circumstances of the case to determine if an investigation should be initiated, explained Inspector Thian.

“Police will also proactively facilitate the social support for victims at risk for further violence. For instance, victims who are unable to return to their homes or find an alternative place to stay, police will refer them to one of the four crisis shelters funded by MSF for temporary accommodation,” he said.

“For serious cases, within the victim’s first week of lodging a police report, the police will contact the victims to check in with them and find out if they need further assistance.”

And should victims require social assistance, the police refer them to the nearest Family Service Centre or a Family Violence Specialist Centre with their consent, added Inspector Thian.

“As part of the victim protection, the police will also encourage (the) victim to apply for a Personal Protection Order or an Expedited Order from the court to (restrain) the perpetrator from committing family violence against them.”

But the exact steps usually depend on the case, noted SSS Wee.

“The police will also consider a number of factors, including the profiles of the offenders and the nature of the violence inflicted, in making these assessments,” he said.

In cases where, for instance, victims might not want to disclose information for fear that they put themselves at further risk, officers are trained to “see what is the most comfortable thing for them”, whether it is speaking to a police officer or with social services counterparts, added SSS Wee.

“From there then we can actually encourage them to lodge a police report. So the end goal is to report to the police and (an) investigation will take place and ensure their safety.”

ENGAGING SOCIAL WORKERS

MSF partners with community-based Family Violence Specialist Centres, Child Protection Specialist Centres, Family Service Centres and crisis shelters to provide support and intervention services, including casework and counselling for family violence victims and perpetrators, said SPF in its media factsheet.

MSF’s Child Protective Service and Adult Protective Service also step in to manage “high-risk and egregious cases” which require statutory intervention under the Children and Young Persons Act, Vulnerable Adults Act and Women’s Charter.

“If violence or sexual offences have been committed, the community-based centres work closely with the police to support victims through the process of reporting and investigations of the alleged offences,” said SPF.

In “clear cut” cases where victims agree to be referred to social services, social workers would first work with the victim to understand “the best way to engage the perpetrator” once they receive the police report, said social worker Ms Lam.

“This is because some perpetrators may feel very ashamed if somebody calls them or they may feel intruded if we call them during their working hours. But some of them may prefer to be called at a certain time or a certain place, or to have the topic broached in a certain manner. So we will speak to the victim first then we'll work with the perpetrator.”

With perpetrators, the first thing to establish is the “no-go zone”, said Ms Lam.

“So what does the law say? What does PPO entail? What are some of the things that are considered not acceptable as far as Singapore law is concerned within the family? After that, we will establish reasonable plans that they can keep to.”

Managing the risk at home is key, as social workers want the family to stay together as much as possible, added Ms Lam.

To do this, they work with perpetrators to understand why they choose violence as a method to get what they want or what are the things they aren’t happy with.

“We are not justifying the act of violence, but we want to give them that platform to talk about it before we can talk to them about how they can then change and what are some alternative ways of intervention at home,” she said.

If a family is ready to receive help, social workers would take about three months to work through any issues that may cause the violence to take place. This “recreates a norm in terms of interaction pattern at home”, explained Ms Lam.

Another six months is required to maintain that norm of “non-negative, neutral interaction”.

Once a family is more ready to receive help, usually at the nine-month or one-year mark, social workers then work with the family on “positive communication”, such as how to share negative information or emotions in a non-judgemental manner.

“So usually for family violence situations, it takes at least one year, one-and-a-half years, for us to establish from negative communication with acts of violence to neutral to positive communication,” said Ms Lam.

WHEN VICTIMS ARE “AMBIVALENT”

However, in cases where the victim is “ambivalent about their situation”, Ms Lam said police would ask if they would be open to a call with a social worker before deciding if they want to engage their help.

During this call, social workers would attempt to address some of the victim’s concerns.

“More often than not, victims’ concerns are all the common ‘what ifs’. What if the acts of violence get worse after police and social workers get involved? What if I can no longer stay with my family when that happens? What if the perpetrator feels very ashamed and that spells the end of our relationship? What if nobody actually believes me?” said Ms Lam.

“What if I make a police report again, and then later on I’m being threatened with other things or the perpetrator refuses to give finances and all that, then what can I actually do about it?”

And in cases where the victim simply does not agree to speak to a social worker, Ms Lam works with police officers to understand the situation without getting exact details on the family involved, so she can provide resources or information via the officer.

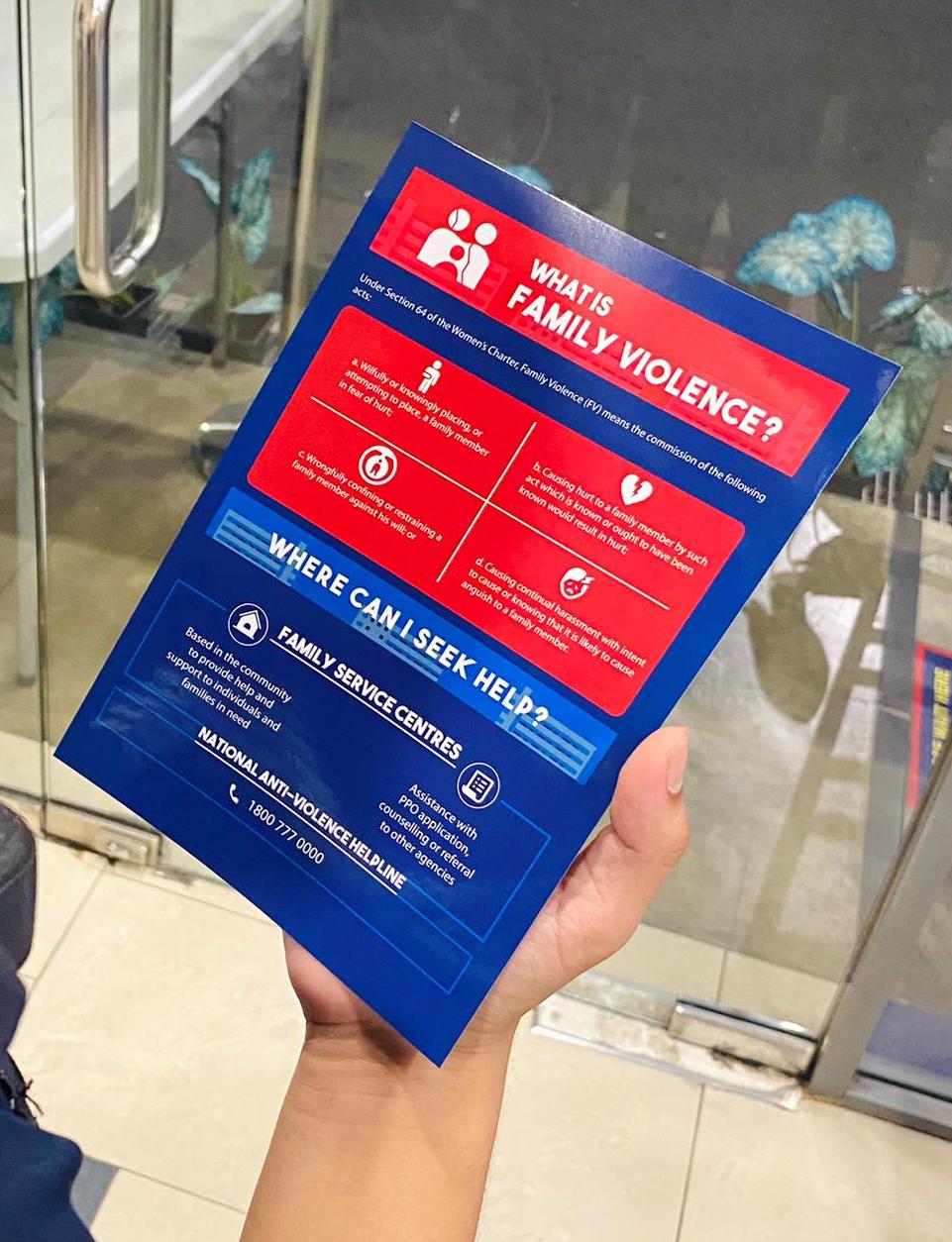

Information pamphlets available

To empower victims of family violence with the knowledge of when and where to seek help, the police have also worked with several SSAs to produce information pamphlets.

These pamphlets contain the following:

- Definitions and signs of family violence

- Information on applying for Personal Protection Orders

- The National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline

- Other useful resources for various scenarios, such as the e-locator for Family Service Centres, and information on family guidance order screening for families with children or youth with behavioural concerns

While these pamphlets are currently being piloted at the Central Police Division and the Ang Mo Kio Police Division, the police aim to make these pamphlets publicly available online and at the rest of the neighbourhood police centres and posts by June 2023.

NOT REALISING THEY’RE ABUSED

Even when victims are willing to receive help, there are hurdles to overcome.

Ms Lam has noticed the “boiling frog” syndrome in several cases.

This refers to the urban legend of a frog being slowly boiled alive. The premise is that if a frog is suddenly put into a pot of boiling water, it would leap out and save itself. But if a frog is put into water with the temperature slowly rising, it wouldn’t perceive any danger and will be cooked to death.

“A lot of times when people experience violence, it’s like a frog in hot water. The water gets warmer over time. Initially, the victim will tell themselves, ‘I want to forgive and forget, let’s see whether he will change.’ Yet, over time, it will constantly get worse,” she explained.

“By the time they reach a social worker, they may not realise they’re being gaslighted. They may not realise that certain demands of the perpetrator actually already crossed the line of emotional abuse, already crossed the line of financial abuse, already can be considered coercive control.”

And so, when a social worker finally explains to them the progression of their abuse, “they are usually very shocked because they have never understood their situation as bad”, said Ms Lam. “They don’t realise they are victims.”

Addressing the misconception that physical violence is more damaging, Ms Lam noted that psychological abuse increases the risk of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and even suicide.

“It causes the victim to be hypervigilant, being very preoccupied with the issue of violence, not being able to make decisions on their own,” she said.

PARENTAL ABUSE IN SINGAPORE

Among family violence cases, one particular group stands out to Ms Lam for their “difficulty in stepping up”. These are the parents being abused by their children.

She recounted cases where victims, aged 50 to 60, have “never made a decision” on what brands to buy at the supermarket because the perpetrator would check the receipts whenever the victim reached home.

“They don't know how to make a decision or they cannot trust themselves to make a decision,” she said.

“In Singapore culture, a lot of times it’s like, ‘I don’t want to wash dirty linen in public.’ And a lot of the elderly may feel like, ultimately, this is my child, I don’t want to bring harm to my child. If I really were to seek help, will I lose this relationship?” added Ms Lam.

“I have perpetrators who tell the elderly things like, ‘If you decide to do this and that, then I will make sure that I will not be there for your wake, and you cannot go to heaven.’”

Some parents even bought into the idea that they were bad parents, which resulted in abuse from their children, she said.

In such cases, Ms Lam has found that repeated home visits from police officers can be helpful. It shows the perpetrator that “somebody is observing, witnessing, checking in and their behaviour is not okay”, increasing deterrence.

For the abused elderly, it shows that somebody cares.

“Even though the police report was long ago, even though (the victim) keeps telling them, ‘Thank you but no thank you’, they still keep coming back, they still keep checking in. … That increases their willingness to call the police the next time there is an incident of violence,” she said.

And once victims see that the system is “on their side”, they too begin to change.

“I had a victim who called me to say, ‘I take bus for the first time.’ Can you imagine how bad the violence escalated?,” said Ms Lam.

Where to get help:

National Anti-Violence Helpline (24 hours): 1800 777 0000