IN FOCUS: Will Singapore meet its 30 by 30 food sustainability goal?

Farmers tell CNA why "grown in Singapore" is still a challenge, and what needs to change for the country to meet its goal of producing 30 per cent of its nutritional needs locally.

Singapore aims to meet 30 per cent of nutritional needs locally by 2030. But the share of total vegetable and seafood consumption that is produced locally has fallen. (File photo: iStock)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When farmer Benjamin Ang harvests beefsteak tomatoes, shishito peppers and Jerusalem artichokes from his greenhouse in Redhill, he has the sense that he is “selling more of an experience than just nourishment”.

“People will buy it because it (feels) good on an emotional level,” he said of the vegetables grown at Natsuki’s Garden, the farm he ran as a one-man operation.

“There have been countless times when friends or customers said they don’t eat a certain vegetable (and) end up asking for more after trying the produce I grew.

“Some expats have told me they dream of being home with family after eating our produce.”

The response convinced Mr Ang, also the director of horticulture at Artisan Green, that good, locally grown produce is appreciated in Singapore.

The question, he said, is whether Singapore farms can produce high-quality produce at a price that people are willing to pay.

Singapore has experienced setbacks in its “30 by 30” vision – to produce 30 per cent of its nutritional needs locally by 2030.

Earlier this year, it was reported that indoor vegetable farm I.F.F.I shut down while VertiVegies abandoned plans to build a mega vertical vegetable farm.

Last year, Barramundi Asia stopped farming sea bass in Singapore due to a deadly scale drop disease outbreak, while Apollo Aquaculture Group entered judicial management.

Productive farms are not immune either. Universal Aquaculture, a vertical indoor farm that was producing about 33 tonnes of vannamei shrimp per year, is set to move out of Singapore after its lease at Tuas South Link expired in November 2023.

It is not just about supply. The proportion of locally grown vegetables and seafood eaten in Singapore has fallen since the “30 by 30” vision was announced in 2019.

In 2023, 3.2 per cent of vegetables and 7.3 per cent of seafood eaten were grown in Singapore, down from 4.5 per cent and 7.9 per cent respectively in 2019.

Only eggs have done better, rising from 25.7 per cent of total consumption in 2019 to 31.9 per cent in 2023.

The “30 by 30” vision has proven to be an immense and complex undertaking. Local farmers told CNA about the challenges they face in an industry of intense competition.

These challenges include high costs, lower economies of scale and a lack of technical support. This can mean that “grown in Singapore” food is priced higher than imported produce – a barrier for price-sensitive shoppers.

WHAT CONSUMERS WANT

What do consumers look for when they buy groceries?

Shoppers in Singapore are price sensitive, according to the results of a YouGov survey commissioned by CNA and interviews with industry insiders.

In the survey of 842 people, 41 per cent said they mostly or always prefer local over imported vegetables. For eggs and seafood respectively, 48 per cent and 32 per cent preferred local.

But those who are “neutral” about the sources of their food form the majority – 54 per cent, 48 per cent and 60 per cent for vegetables, eggs and seafood respectively.

How can this group of neutral consumers be won over?

In the survey, consumers who chose imported food over locally grown food cited lower prices, the perception of better taste or quality and the variety on offer as their reasons.

In contrast, freshness, being pesticide-free and food safety were key factors for consumers who prefer locally grown food.

A sizeable number also said they chose Singapore produce to support local farmers – 40 per cent of those who buy vegetables and eggs, and 31 per cent of those who buy fish and seafood.

This gives some idea as to how messages can be tailored to tout the advantages and change perceptions of local produce in public education or marketing campaigns.

CEO of APAC at YouGov Laura Robbie said the data shows that freshness is a top factor among Singaporeans who prefer buying local.

“Price is important, but quality and safety of food assume greater priority,” she added.

Professor William Chen, director of the Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Food Science and Technology Programme, said: “Human beings are conservative, and by and large, we tend to stay in our comfort zone unless we are pushed.”

Locally grown food does beat imported food not only in freshness but also nutritional value, as it does not need to be harvested early and spends less time in cold storage and in transit, he added.

Ms Eyleen Goh, director of rooftop farm SG Veg Farms, said that while awareness of local produce is increasing among consumers, there is not yet a “strong sense of pride” about food grown in Singapore.

There may also be specific food myths – like perceptions of wild-caught versus farmed seafood – that can be busted.

Ms Victoria Yoong, who founded land-based seafood farm Atlas Aquaculture with her husband Kane McGuinn, said that in Singapore’s multi-generational households, marketing is often left to older generations.

Older folks prefer to eat tropical fish like threadfin and marble goby – which Atlas Aquaculture farms – over the likes of imported salmon, said Ms Yoong.

But they also tend to associate all farmed fish with a “muddy taste” that is the product of bacteria when fish are grown improperly. This may put them off locally farmed fish entirely, she said.

IS IT ALL ABOUT THE PRICE?

Still, there is no escaping the fact that lowering the prices of local produce matters immensely to consumers.

When asked whether lower prices would encourage them to buy more local produce, 88 per cent of respondents said it was likely – including almost half who said it would be very likely.

This is more than the 83 per cent who said they are likely to be persuaded if they are given more information about the quality of local produce.

It is also more than the 78 per cent who say that more prominent displays of local produce in supermarkets are likely to help.

“While there is an intent to buy local, many are unable to identify the origin of the produce,” said Ms Robbie.

“More prominent displays in supermarkets, along with additional information about the quality and sourcing process of local produce, may help address this and enable informed choices.”

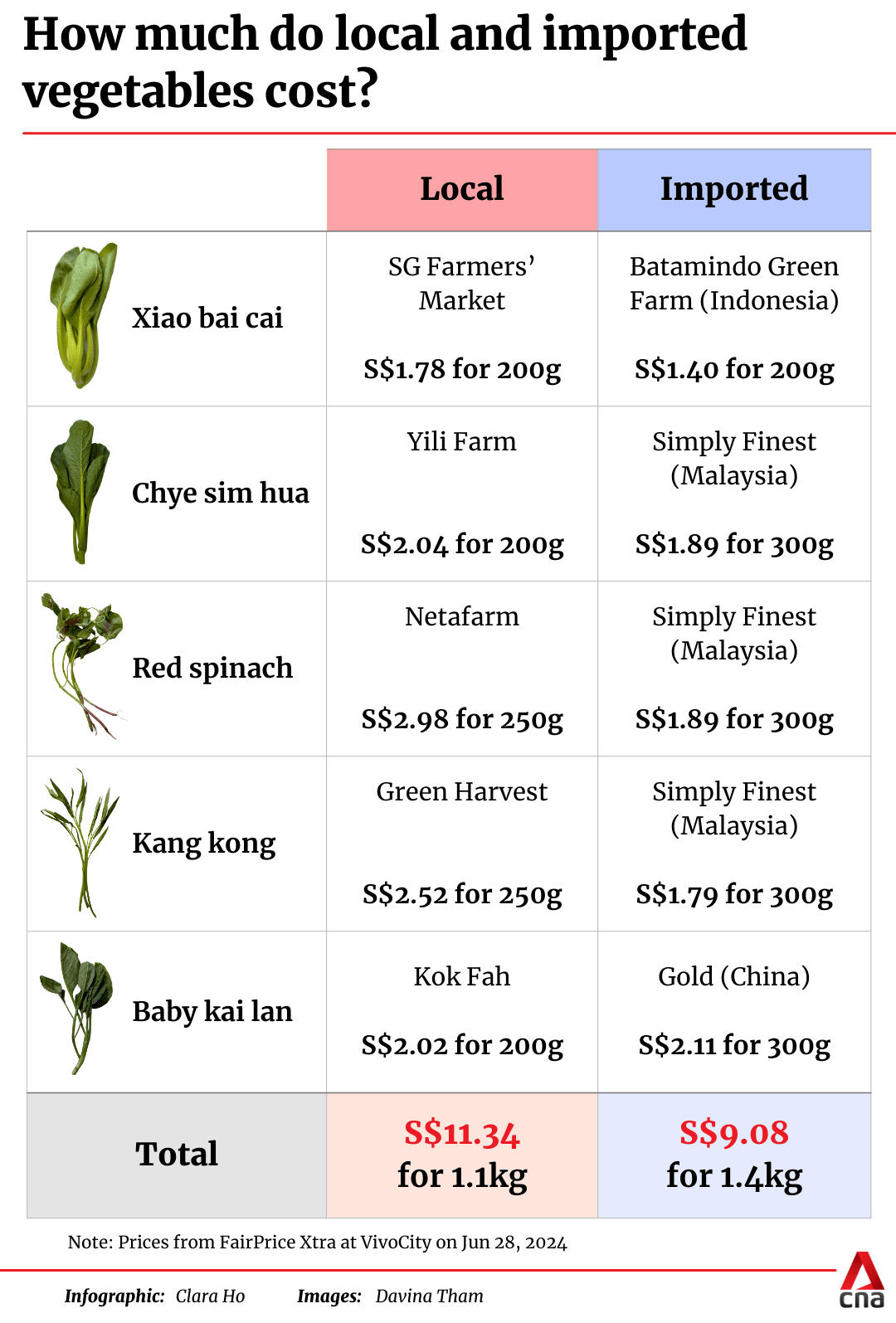

Last month, 13 FairPrice supermarkets debuted a new line of affordable local vegetables and seafood under the brands SG Farmers’ Market and The Straits Fish respectively.

Local lettuce, chye sim and xiao bai cai go for as low as S$1.78 for a 200g packet, while local tilapia is sold at S$4.90 for a whole fish or S$5.90 for sliced fish.

Sales have been encouraging, and there are plans to roll out SG Farmers’ Market products to 44 more FairPrice outlets by the end of August, FairPrice Group told CNA.

The company said this collaboration, with the Singapore Agro-Food Enterprises Federation, was its first time working with a local organisation on an aggregator business model.

A quick glance at supermarket shelves shows that locally grown greens tend to cost more than their imported counterparts.

KEEPING COSTS DOWN

In land-scarce, labour-scarce and water-scarce Singapore, indoor farming and recirculating aquaculture systems have emerged as solutions to increase the production of vegetables and seafood.

This entails high energy costs, which together with expensive labour is the biggest contributor to costs of production in Singapore, farmers told CNA.

Land rent, outsourcing of food processing, sorting and packing, as well as the cut that supermarkets and distributors take also add up.

“You can’t just grow the plant. Because the vegetable itself is so low value relative to your costs,” said Mr Ang, the farmer.

“You really need to have the value-add of being able to package it, being able to sell it in some unique way. And then once you add that in then it’s just a ... very complex operation.”

Regional competitors intensify cost pressures on Singapore’s farms.

For example, Singapore imported almost 127,000 tonnes of seafood last year, compared with more than 4,000 tonnes grown locally. The top sources were Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam.

Ms Yoong of Atlas Aquaculture, which also co-owns two seafood farms in Sarawak and Lombok, noted that labour and energy costs were drastically lower there, and land was “essentially free”.

While Atlas Aquaculture’s 2.1ha farm in Singapore – which produces 100 to 150 tonnes of seafood a year – was on the verge of breaking even, the two co-owned farms in Sarawak and Lombok have already turned a profit.

In Singapore, some vegetable farms have stayed outdoors to harness the sun’s rays and avoid high energy costs. The savings can be significant.

SG Veg Farms is located on the rooftops of two multi-storey car parks in Sembawang. Every day, the farm produces about 200kg of mainly Asian leafy greens like xiao bai cai and chye sim.

Natural sunlight streams into the greenhouses and only the nurseries have LED lights. The farm uses a mechanised system to move hydroponic trays into place, and precision farming tools.

Ms Goh, the company’s director, said the farm’s ecosystem was adapted from “proven models” used in large overseas farms, and that electricity accounts for 10 to 20 per cent of costs.

Professor Paul Teng, a food security expert at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, emphasised the “judicious use of technology” in local farms that are price competitive.

While technology is important, he cautioned against choosing the “tech push” over a “problem pull” approach.

“The tech push means that you have scientists and armchair planners saying this technology is great, let’s use that technology,” he said.

“Whereas in the private sector and logically, in development circles, we say that we should always start by defining the problem.”

CHOOSING THE RIGHT CROP

It is not just local factors of production and technology that determine costs – the choice of crop is also crucial.

Existing indoor farming systems tend to be designed for vegetables like lettuce rather than Asian leafy greens, according to Prof Veera, who is also a Professor in Practice at the National University of Singapore’s Department of Biological Sciences.

Local indoor farmers face a “double whammy” of high costs and the fact that existing seeds for Asian vegetables do not necessarily grow well indoors, he said.

NTU’s Prof Chen said that it makes business sense for indoor vegetable farmers to grow exotic greens like kale and microgreens, because these have better profit margins than Asian leafy greens.

There is a “mismatch” in using high-tech farming methods to grow cheap leafy greens, he said.

Yet Asian leafy greens form the bulk of the local diet and according to farmers, are what local consumers want.

Prof Chen believes that one way around this conundrum could be to allocate more land and support to mushroom farming.

According to him, mushrooms are in the sweet spot of food that is familiar to local consumers; nutritious with fibre, amino acids, vitamins and minerals; and less energy-intensive to grow as they do not require light.

Some experts also recommend a return to legacy foodways. RSIS’ Prof Teng pointed to indigenous vegetables like mani cai and wing bean as being resilient to pests and diseases, as well as being easy to grow in Singapore’s climate.

GETTING GRANTS

The choice of what to grow and how to grow is not made by businesses and scientists alone, but also shaped by how food resilience is scoped in policy.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when Singapore braced for supply disruptions, the “30 by 30” vision that was launched in 2019 gained a sense of urgency.

In April 2020, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) launched the 30x30 Express grant to accelerate local food production over the next two years.

Close to S$40 million (US$30 million) was awarded to nine farms, including VertiVegies and I.F.F.I. VertiVegies later declined the grant before the money was disbursed.

When CEO Jeremy Ong was setting up Universal Aquaculture in 2020, his calculations led him to conclude that the business would only be viable if he grew vannamei shrimp.

At the time, sea bass from Malaysia was selling for S$5 to S$7 per kg, and tilapia for S$3 per kg. Yet it would cost about S$26 per kg to grow these fish at his farm in Singapore.

In contrast, he would be able to grow and sell vannamei shrimp at a profit.

But when Universal Aquaculture applied for the 30x30 Express grant, he said he was told that “prawns are not food in our eyes”. The farm instead received a smaller test bedding grant of S$100,000.

To keep the farm in the running for the 30x30 Express Grant, “we could have said that we would grow sea bass”, said Mr Ong. “But then we would end up being operationally unprofitable.”

Universal Aquaculture went on to produce 32 to 33 tonnes of vannamei shrimp a year at its facility in Tuas South Link.

Mr Ong said the view that “prawns are not food” has changed over time, in part through industry exchanges with regulators.

Shrimp is now explicitly listed among the types of farms that can receive funding support under the existing Agri-food Cluster Transformation (ACT) Fund, which has a S$60 million purse.

As of April, S$25.7 million has been awarded to support 68 projects under the ACT Fund.

In response to CNA’s query, SFA said that funding proposals are evaluated based on comprehensive criteria such as “technical feasibility, track record, productivity outcomes and economic viability”.

“While SFA does not specify the types of vegetables and fish or seafood to be produced, companies must demonstrate consideration of market demand and commercial viability of their products,” the agency said.

The ACT Fund has a capability upgrading component where each applicant can receive up to S$200,000 to buy farming equipment and to support trials to raise productivity and resource efficiency.

The fund also has a more generous technology upscaling component that provides up to S$6 million to buy farming technology, and set up a new farm site or retrofit an indoor space.

But SG Veg Farms’ Ms Goh said that although current grant assessments are valuable, they miss certain needs and constraints of urban farms.

The company applied for the technology upscaling grant under the ACT Fund, but received a smaller productivity grant that helped to pay for parts in its mechanised farming system.

“The grant assessment was purely focused on whether the farm is using new technology and design,” she said.

There could also be a grant to support the adaptation and localisation of existing farming technologies, she suggested.

Operational costs after the farm has been set up are “the primary reason for many farms struggling to survive”, Ms Goh said, adding there could be grants for post-production such as processing, sorting, packing and delivery.

Ms Goh also suggested that grant assessments place more emphasis on sustainability metrics and environmental impact, “rather than just immediate technological innovation”.

“WE ARE NOT AN AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY”

More fundamentally, some farmers pointed out that Singapore lacks the industry support they need to realise the “30 by 30” vision.

“We don’t have the ecosystem. We’re not an agricultural society,” said NUS’ Prof Veera, who added that there should be a “moderation of expectations” around local food production.

Mr Ang, of Natsuki’s Garden and Artisan Green, likened the gulf in expectations and reality to “trying to hold a concert before making the stage”.

One thing that Singapore lacks is a central body that supports farmers technically, he said, pointing to the Cooperative Extension System in the US as an example.

The extension system is an educational network that comes under the Department of Agriculture. As part of the system, universities carry out agriculture-related research and share their knowledge freely with farms.

“They have diagnostic services with very short turnaround times so farmers can address disease issues quickly,” said Mr Ang.

In contrast, the typical timeframe needed to identify a disease in a plant sample in Singapore is three to five weeks, according to him. “That’s nowhere near what the industry would need to perform,” he said.

Mr Ang, who studied horticultural science in Florida, believes that Singapore needs more horticulturalists who have a deep understanding of how to grow plants and are up to date with agricultural technology.

“If you go to the farms in the US or Europe, you will see how ridiculously far behind we are in what we do, and people don’t even know that,” he said.

Farmers also pointed out that food resilience is not only about growing the produce, but making sure everything needed to grow the produce is in hand.

In that regard, Singapore lacks feed mills and fertiliser manufacturers, they said. There is also the matter of ensuring access to seeds and baby fish or shrimp.

Mr McGuinn of Atlas Aquaculture said that food security requires “everything from start to finish, and there’s none of that” in Singapore.

“Even if we grow 30 per cent (of nutritional needs), in a time of need for food security, the same countries that would cut you off – which is the risk – are the ones that have the feed for the fish, the babies,” he said.

Tackling this would mean putting more resources into research for local seed development and production, as well as local breeding and hatchery programmes for seafood.

Listen:

THE SUCCESS STORY: EGGS

Unlike vegetables and seafood, eggs have grown in local production volume since the “30 by 30” vision was announced. Local eggs first crossed the 30 per cent mark of local consumption in 2021.

There are three egg farms in Singapore – Seng Choon Farm, Chew’s Agriculture and N&N Agriculture.

The disparity in the performance of vegetables and seafood farms is because of how the market is set up, according to Seng Choon Farm’s managing director Koh Yeow Koon.

“The egg industry is a unique player in the market, with a single product – hen shell eggs,” said Mr Koh, using the industry term for chicken eggs.

“When high-tech egg farms were first set up in the late 1980s, we only competed with one overseas source with slight feed cost disparity.

“Then, crucially, the competition was narrowed to source farms that are free from Salmonella enteritidis, a critical public health safety concern.”

This cleared the way for local eggs to win market share.

In contrast, vegetable and seafood farmers have diverse varieties and various sources, such as wild-caught or farmed fish.

“They contend with a broader price range and smaller market base, making it challenging to achieve economies of scale,” said Mr Koh.

Vegetables and seafood also face a “staggering price differential” compared with imports, making it difficult to stay competitive, even with grants and subsidies.

That is not to say there are no challenges in local egg farming.

“Feed costs account for a whopping 70 per cent of the production cost of each egg,” said Mr Koh, adding that Singapore’s small agricultural base means it does not enjoy any cost savings when it imports feed ingredients.

Seng Choon Farm produces 550,000 eggs daily, making up about 10 per cent of eggs eaten in Singapore.

Mr Koh said that while the farm cannot compete against imports on price, it leverages freshness and locality to stand out, such as through same-day delivery.

“It is still an uphill task for us as we are always chasing an ever-expanding pool of highly efficient overseas competitors,” he said.

“Despite our best efforts at running, we have only managed to keep the price differential of eggs roughly consistent at about 20 per cent for the past 35 years.”

CREATING STEADY DEMAND

Seafood farmers Mr Ong and Ms Yoong both raised the possibility of co-ops that would buy produce from farmers, including for the national stockpile of essential items.

This could provide farmers the assurance of selling their produce at a price where they can “maintain a decent margin and survive”, said Mr Ong.

NTU’s Prof Chen suggested leveraging schools, public hospitals and the Singapore Armed Forces for such demand.

Singapore could also be more strategic in its trade agreements and diplomacy to shore up food resilience, said experts.

RSIS’ Prof Teng added that Singapore could forge more supply chain continuity agreements with countries with which it has good relations. He cited India, which exempted Singapore from its rice export ban in 2023, as an example.

He suggested that the government pursue overseas farming arrangements with countries that historically have a surplus of agricultural produce, such as Australia and New Zealand.

When it comes to the future of local farming, the farmers who spoke to CNA balanced hope and realism.

“Local agriculture will persist. In time we may even perform well. But not in the timeframes that have been proposed, and certainly not enough to feed our local population,” said Mr Ang.

Methodology: YouGov Surveys: Serviced provides quick survey results from nationally representative or targeted audiences in multiple markets. This study was conducted online in June 2024, with a national sample of 842 Singapore residents, using a questionnaire designed by YouGov. Data figures have been weighted by age, gender, and ethnicity to be representative of all adults in Singapore (18 years or older) and reflect the latest Singapore Department of Statistics (DOS) estimates.