Deep-sea solution seeding hope for struggling but essential seaweed farming industry

Climate change has had devastating impacts on the commercial seaweed industry across the region. In response, a foundation is developing world-first technology and techniques with a broad plan to empower seaweed-growing communities.

A solar-powered platform used by Climate Foundation to control its deepwater seaweed array. (Photo: Jack Board/CNA)

CEBU, Philippines: After a stormy night, the sea off the coast of Compostela, a small town north of Cebu, has calmed. Right as dawn breaks, a mechanical whirring signals the start of a daily operation.

From an inconspicuous floating platform, in sight of the shore, a unique climate change solution is being tested.

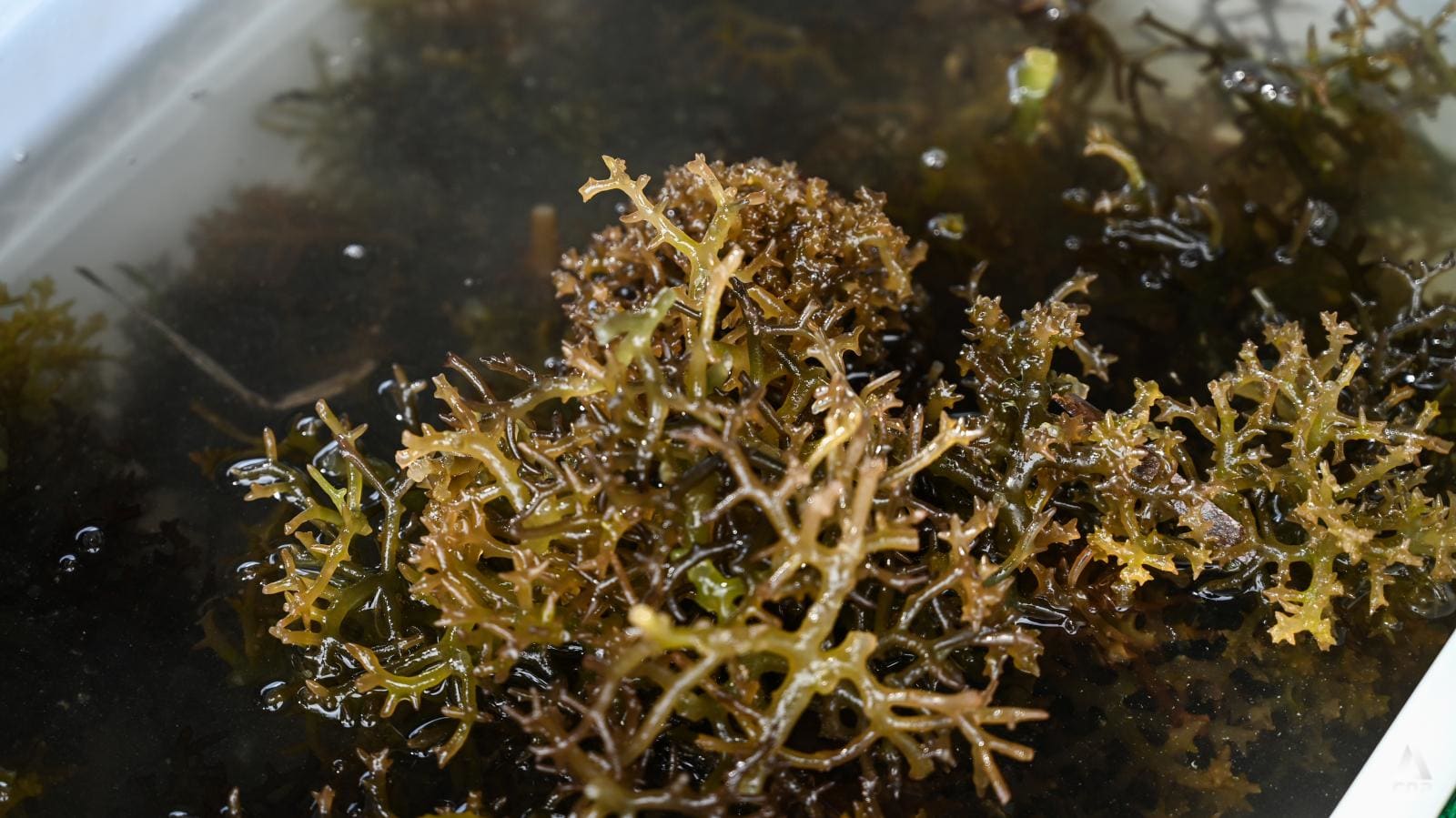

From the depths, slowly, a great forest starts to emerge. It is an 1,000 sq m expanse of seaweed, connected to a submersible ring and winch that has spent the night 120m below the surface.

The seaweed has been soaking up a rich supply of coldwater nutrients, found in abundance in the deep. Now that the sun is rising, the crew here raise the ring to give the seaweed the light it requires to photosynthesis and grow.

The permaculture project is part of an ongoing effort by the Climate Foundation - an independent nonprofit focused on food security and climate change mitigation - to use deep-sea marine permaculture to reinvigorate seaweed farming in the Philippines, and eventually around the world.

It could also have broad benefits for carbon capture - an essential way to slow down climate change - as well as improve food security among vulnerable communities.

“It's about sustaining a seaweed forest. It's about having a sustainable yield for coastal communities. And it's about really ensuring biodiversity and also the nature-based carbon removals that are possible with marine forests,” said Dr Brian von Herzen, executive director of Climate Foundation.

“Whatever we succeed within the Philippines, ultimately, could be scaled by another factor of 10, in Indonesia and other countries.”

DEVASTATING IMPACTS

Climate change has had devastating impacts on the commercial seaweed industry across the region. In the Philippines, it supports an estimated 200,000 families across the country, but is in an increasingly fragile shape.

In Indonesia, the sector is even more important. The country produces more than a quarter of the world’s seaweed, behind only China. The Philippines is the fourth largest global contributor, accounting for less than 5 per cent but seaweed is one of its most important exports.

Climate Foundation is developing world-first technology and techniques with a broader ambition to create a circular-economy model to empower seaweed-growing communities.

Its for-profit subsidiary Seaforestation.co received funding from investors worth S$300,000 at the Liveability Challenge, presented by the Temasek Foundation in June.

The foundation’s offshore seaweed array that can be dropped deep below the surface is designed to solve an issue being faced around the whole world - rising global ocean temperatures.

The warming climate has reduced a natural phenomenon called ocean upwelling, where deep, cold, nutrient-rich waters cycle up to the surface, enriching various kinds of marine life and farming operations.

Because oceans absorb the vast majority of the heat from global warming, those colder waters are now deeper and not upwelling to the surface. Many traditional seaweed operations, as a result, are suffering inconsistent yields and a litany of diseases.

Warmer water also helps give tropical typhoons their energy. Typhoons in the Philippines are becoming more regular, more intense and unpredictable and these monster storm systems regularly wreak havoc on seaweed operations.

“Today, many of these seaweed communities are collapsing due to low production and the challenges whether it's storms, high temperatures, or low nutrient levels,” Dr von Herzen said.

Soon, Climate Foundation plans to launch a prototype hectare-sized array, 10 times the current one, to scale up its potential to financially sustain a community of 30 seaweed farmers and their families.

Once the economically-scaled model is proven with this design, it has ambition to launch such systems in communities at a great scale across the region, leaning on finance from development banks.

“We are literally one step away from an economically sustainable hectare, which we anticipate getting in the water over the next 12 months,” he said. “Our intention is to develop lease-to-own agreements with communities that would enable financing, while effectively working with development banks and investors.”

The first few hectares will be expensive to build, he admits, but expects costs to drop and performance to increase over time. To make a concrete difference, “we will need thousands of hectares”, Dr von Herzen said. “But that's doable.”

“Most coastal communities that have access to deep water should be able to build one of these systems. As we reduce the risk and reduce the cost and increase the performance, this is an exponential growth opportunity.

“This is literally what builds climate resilience into our coastal communities across Asia. And I see that as fundamental because the weather is not going to get any simpler.”

At its research base in Compostela, a small team comprising engineers, biologists, scientists and local fishermen are busy experimenting with seaweed varieties, automation methods and development of by-products from their cultivation.

Through trial and error, they are in the process of establishing which species react best at which temperatures as well as ensuring the platform can withstand storm conditions.

“All the parameters are new. But the quality should be good and the growth rate should be much faster than even traditional seaweed farming,” said marine biologist Eric Smith.

“And the big advantage is just the stability; they'd be able to grow 12 months out of the year instead of relying on dwindling good growth seasons,” he said.

MEMORIES OF THE GOLDEN AGE OF SEAWEED

When seaweed operations started to emerge, then explode, around the island of Bohol - some 50 kilometres south-east of Cebu - in the 1970s, it brought great opportunity for local coastal communities.

For about two decades, farmers on Hingutanan Island could harvest and then process 1,000 tonnes of dried seaweed every month.

A fable that still gets told today tells of the wealth being accumulated by those farmers, that when it was dry season and the island was running out of water, the farmers had enough money to wash their hands with beer instead.

Those days are but a memory now.

Around Bohol, many seaweed farmers have simply abandoned the practice. Seaweed operations and processing stations have disappeared entirely. A monthly harvest of 20 or 30 tonnes per month nowadays is considered a good result.

“It's not the same as before. At times we have no earnings in a whole month,” said Mr Freddie Alimunda, who has been growing seaweed for more than 20 years around Mahanay Island.

“At times we have income but not that much. The problem is we have no financial capacity. My community needs help. I am not losing hope because this is my livelihood."

Production in Bohol has been decimated; in 2022 - a record low year - output was just over two per cent of what it was a decade previous. This year, the numbers have barely improved.

Nationally, the industry is in better shape but there are signs of decline. Production in 2022 was about 16 per cent lower than a peak in 2011. While the past decade has been relatively steady, production in 2023 is down on last year.

Leading seaweed expert, Professor Danilo Largo from the University of San Carlos in Cebu, explained that rising sea temperatures and the ravages of disease have ruined the local economy.

The productivity of seaweed strains that used to thrive has drastically reduced. Ice-ice disease, which resembles bleaching in coral, has spread widely in shallow water farming.

While first observed back in the 1970s, an outbreak in the early 2010s caused widespread economic losses.

“It's really caused by unfavourable environmental conditions, especially water temperature, and high or low salinity,” he said.

“When farmers found out that the seaweed had become diseased with this whitening - this ice-ice disease - that was the time they realised that farming in shallow water was no longer viable.”

Prof Largo is supportive of efforts to focus on deeper water farming, despite the logistical challenges. But he said greater efforts in seaweed innovation and research should be a national priority as well.

“Well, it's gloomy for the Philippines because we’re not innovating so much with the right strains of climate-resistant seaweed. There are so few serious scientists. Those that are still alive are almost retiring,” he said.

“And we have not really abated the rising temperatures. We're still business as usual. No matter what we're doing as scientists - you want to do innovative ways of farming - that's a very difficult factor to control.”

Dr Jayvee Saco from the VIP Center for Oceanographic Research and Aquatic Life Sciences at Batangas State University is more optimistic about the ongoing research his team and others are involved with, focused on seaweed strains with better yields, more resilience and valuable functions.

“I think we need to close the gap between the results of our science to the farmers and actually we're already there. And most of the farmers are very receptive with the technology that we are presenting to them. Because first and foremost, that's their livelihood,” he said.

“They are still the poorest of the poorest. So we need to augment how they can have enough income.”

He said the applications for seaweed and its by-products are vast and often underappreciated. Markets are ready to be further tapped if Philippine farmers can meet the demand.

Carrageenan - an extract of red seaweed - is an example of a ubiquitous food additive in people’s daily lives around the world.

“It’s found in ice cream, bread, cakes, sausages, beer, milk, napkins, diapers, gel pens, makeup. It's everywhere. So there's a lot of potential in the usage of seaweed. It’s a matter of how we’re able to utilise them,” Dr Saco said.

A CIRCULAR ECONOMY

Trying to lift the demand for seaweed and increase its uses across the board is a strategy that Climate Foundation thinks can help the entire industry, especially small-holder farmers who cannot access their developing technology right now.

Already, the foundation is distributing and selling a seaweed biostimulant that can replace conventional fertilisers for rice farmers across Bohol.

It promises less greenhouse gas-intensive agriculture and better rice yields at far reduced costs.

In Bohol, the foundation is buying local seaweed and using cold press machines to extract the juices, before they are sent to be processed into the biostimulant, which farmers can spray directly onto their crops.

The coordinator of the project, aquaculturist Mr Perfecto Tubal believes widespread adoption of the product called BIGgrow could help solve the country’s national food insecurity problems.

Improved rice yields could reduce the Philippines’ dependence on imports and lead to lower prices for consumers.

While local trials of the biostimulant are ongoing, local rice farmers that CNA met seemed pleased with the results of using it instead of fertilisers from overseas, which is a major cost for growers.

“You will see the effect of it on the rice plant. The way it looks, it’s very different. The shape is different. It’s very strong and healthy looking. Unlike my brother-in-law, it looks like he has lots of pests,” said rice farmer Wilfredo Haya Quilas.

“We just decided to change so that our rice field will not be acidic anymore,” said Ms Glosaria Limbaga, a fellow rice farmer. “We feel it is much better compared to what we used before.”

As well, local aquaculture farmers are being encouraged to incorporate waste from sargassum seaweed into their feed for shrimp and fish, instead of importing chemicals. That waste can be directly taken from the juice extractors.

The same process has potential to be used to feed cattle or pigs, with peer-reviewed research in other countries showing the clear benefits that seaweed in livestock diets can have to reduce methane gas, a major contributor to emissions that cause climate change.

For now, the major challenge is ramping up supply from a seaweed heartland that barely has a pulse.

By localising greater seaweed cultivation and multiplying direct revenue streams from it, Dr von Herzen is confident about realising a greater dream, for local communities and the planet.

“How do we build a civilisation that can continue to exist on our planet sustainably into the coming decades and into the next century? This is all about building sustainability into everything we do,” he said.

“It's about actually not only increasing production of seaweed, but increasing the revenue that the community sees. Much more of a percentage of every tonne of seaweed revenue is actually staying in the community, whether it's the seaweed farmer or the rice farmer.

“And so this is building a circular economy around the thousands of islands that exist in the Philippines, even more in Indonesia, and in other countries across Asia.”

Additional reporting by Nicole Revita.