Can biohacking rewrite the human operating system?

The biohacking community embraces methods that vary widely. Some focus on very precise tweaks to their diet, sleep and exercise, while others turn to technology, embracing treatments such as red light therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

The amorphous biohacking community embraces methods that vary widely. Some focus on lifestyle tweaks – adjusting their diets, practising intermittent fasting, or fine-tuning their sleep and exercise routines. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

A typical day for 43-year-old entrepreneur Nicholas Lin begins when he wakes up fresh and clear-headed after the seven hours of uninterrupted sleep he makes sure he gets each night.

Breakfast is washed down by a ritual stack of 34 supplements he takes religiously each morning. Among them are berberine, glycine, fish oil and biotin – all part of a supplementation protocol he has fine-tuned over the years.

Mr Lin consumes 2,050 to 2,250 calories a day, outside of the roughly 16 hours he spends fasting. His meals are built around 180 to 200 grams of protein, drawn from grass-fed beef, eggs, broth and protein powder, among other sources.

His evenings end with a low-impact strength and conditioning workout – part of a daily 20- to 30-minute exercise routine.

He also spends about an hour daily in what he calls his "anti-ageing room" – a space lined with equipment designed to optimise his body as he ages.

These include red light panels, which he uses for 10 minutes every two days to support cellular rejuvenation and reduce inflammation, and an oxygen concentrator he runs nightly to potentially boost oxygen levels during sleep.

Every detail of his regimen is meticulously logged in a 10-page document: from his diet, nutrition plans and supplement stacks, to skincare routines, fitness schedules and the catalogue of equipment he uses.

Mr Lin said he started taking such detailed care of himself as he was driven by a desire to optimise his performance – to see if he could keep feeling as physically and mentally fit in his mid- and late 40s as he did in his 20s.

"I thought about what my mental and cognitive peak of my life was, and I figured that was around 26 or 27 years old, so I set up a goal to achieve that, like de-aging myself by almost 20 years," he said.

"And then it became a little bit of an obsession over the last 13, 14 years to go and figure out how to subtly improve certain aspects of life, certain biomarkers, and to just turn the clock back."

He began tracking his protocol in a more detailed manner around seven years ago.

"Before that, it was mostly experimentation and trial-and-error, trying to understand how to counter the poor lifestyle choices that most of us make as humans," he said.

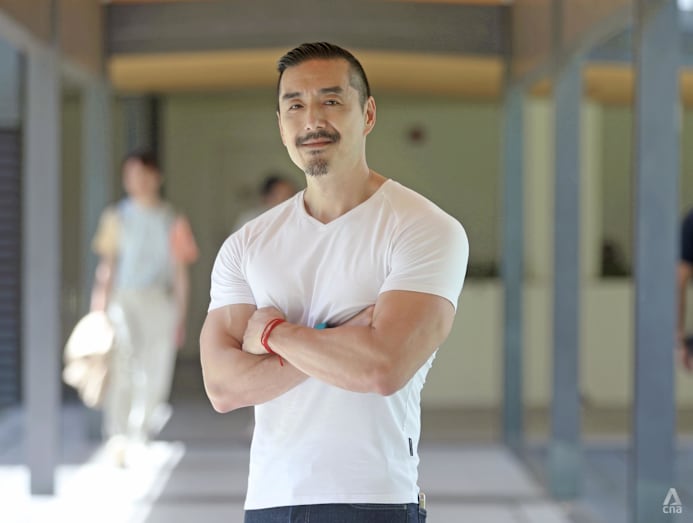

Mr Lin considers himself a "biohacker", one of a growing community around the world. Fellow biohacker Vignesa Moorthy, 52, hopped on the movement after his mother's cancer diagnosis in 2019, which spurred him to take charge of his own health.

He did not just want to live longer, but to live better and maintain the "best quality of life" even as he ages.

Driven by a desire to create what he calls the "most optimal" outcome for ageing, the founder and chief executive officer of cybersecurity firm ViewQwest began introducing biohacks to stay mentally sharp and physically strong for as long as possible.

He has since overhauled his lifestyle – cutting out alcohol and cigarettes three years ago, prioritising sleep and exercising daily. Each month, he does a three- to four-day water fast, where he abstains from food and drinks only water to "rid (his body) of toxins".

Beyond prioritising what he calls the "fundamentals" – eating and sleeping well and having good social interactions – Mr Moorthy has also built a personal longevity lab of sorts at home, equipped with a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, red light panels and a cryotherapy unit.

"Every step is a data-driven exercise," said Mr Moorthy, who tests new interventions and monitors their impact through wearables, blood tests and logs of how he feels. He estimates spending about S$50,000 (US$38,500) a year on biohacking, including treatment bills, upkeeping machines at home and regular blood work.

Every two to three months, he undergoes a full blood panel, and he said that his results today are the best they have been in three decades.

"You're looking at things like liver function, lipids, calcium scores, all sorts of things. And for me, it's been really good. Even my doctor also said: 'Wow, I'm really proud of what you've been able to achieve'."

For Professor Dean Ho, it began with a blood testing kit he bought as a birthday gift to himself in 2021 – a simple tool to track his glucose levels as he practised a daily fast.

That small step soon set him on a path to optimise lifestyle interventions, exploring how science and data could improve health, drive change and enhance everything from human performance to ageing.

The director of the Institute for Digital Medicine (WisDM) at the National University of Singapore's Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine) said: "I started pricking my finger to look at things like metabolic switch – when we switch from sugar burning to fat burning. And my first readings were very underwhelming.

"I continued to stay at it. And then eventually, when I metabolically switched and saw the first reading I got, I was absolutely hooked. I could actually see real change in my system," said Prof Ho, who is also head of the biomedical engineering department at NUS College of Design and Engineering.

He was not aware of it at the time, but this had a gamification effect on him. He resolved to stick with a stricter fasting regimen, abstaining from food about 16 hours each day.

He then began collecting his biomarkers multiple times during the day.

"I started to see this very unique kind of V-like structure: In the morning my ketones are high when I'm in ketosis, but then I exercise, which then causes my glucose to go up because I'm releasing sugar, and then this causes my ketones to go down because I have sugar in my system again. And then as I finish my exercise, I just watch my ketones rebound right back.

"I started to repeat this every day."

Ketones are chemicals the body produces when it breaks down fat for energy due to a lack of glucose. In metabolic switching, the body shifts from using glucose as its primary fuel to burn fat to producing ketone bodies for energy.

Low ketone levels mean the body is mainly using glucose for fuel, while moderate levels indicate it has begun burning fat for energy.

Today, Prof Ho is also the sole test subject in a double ethics board-approved study called "Delta", working with a team of 16 researchers from NUS' Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, the College of Design and Engineering, and the National University Health System (NUHS).

The project aims to provide a framework for mapping and understanding each person's unique "delta", or the changes that define their individual health trajectory.

The goal, he said, is to translate findings into a longitudinal, data-driven and evidence-backed healthcare approach – one that could eventually be scaled to larger public cohorts.

Since that first finger prick in 2021, he has introduced a range of interventions to better understand his delta.

These days, he fasts about 20 hours a day, eating only between 11am and 3pm. Twice a week, he switches to a plant-based diet. He also exercises daily, turns in by 9.15pm, wakes up at 6am and makes sure to get all his caffeine in before 7am.

"Data became my medicine," said Prof Ho.

"One of the things that I looked at (through the Delta trials) was my functional metabolic outcomes, and my metabolic performance probably rivals that of my kids right now, who are 11 and 12.

"My insulin is about as sensitive as it can possibly be, regardless of age, and not (just) for a 46-year-old."

Like Mr Lin, Mr Moorthy and Prof Ho, there are a growing number of individuals around the world who experiment with interventions to improve their health, optimise performance, and, in some cases, extend lifespan.

The amorphous biohacking community embraces methods that vary widely. Some focus on lifestyle tweaks – adjusting their diets, practising intermittent fasting or fine-tuning their sleep and exercise routines.

Others turn to technology, embracing treatments such as red light therapy, which uses low-level wavelengths of red light believed to improve skin conditions and promote healing, or hyperbaric oxygen therapy, where pure oxygen is delivered in a pressurised chamber to boost oxygen flow in the body.

It's become a movement – one that merges science, self-optimisation and the age-old pursuit of better living.

DATA-DRIVEN WELLNESS

Although biohacking has grown in popularity in recent years, the concept itself isn't new.

At its core, biohacking is a continuation of what people have done for decades: pursuing better health through regular exercise, sufficient sleep and a balanced diet.

But today's biohackers have taken that instinct further, tracking every detail, from calories and sleep cycles to blood glucose levels, with precision, and blending wellness with data-driven methods to fine-tune how their bodies function.

Powered by advances in science and technology, biohacking has evolved beyond lifestyle tweaks into a realm of experimental treatments such as red light therapy, cryotherapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy – all designed to enhance the body's performance.

Once confined to clinical settings, these interventions have now found their way into homes and daily routines.

In the United States, tech tycoon Bryan Johnson, 48, has become one of the most visible champions of biohacking, promoting his "Don’t Die" philosophy – a fringe movement that has gained a cult-like following among longevity enthusiasts worldwide.

His regimen is notably disciplined: He wakes at 4.30am, consumes all his meals before 11am, and goes to bed by 8.30pm. He also takes more than 100 supplements and works out for at least an hour each day, all in the name of slowing the biological markers of ageing.

For a time, Mr Johnson made headlines for receiving blood transfusions from his teenage son. He has since abandoned the plasma-swapping practice – a controversial trend apparently popular among the ultra-wealthy seeking to preserve their youth – after finding that it offered no real benefits.

Mr Johnson reportedly spends an average of US$2 million a year on his anti-ageing regimen – a level of investment that few can afford.

It's little wonder, then, that biohacking appeals mostly to affluent men in tech, startup, entrepreneurial and finance circles.

Dr Shannon Ang, an assistant professor of sociology at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), said biohacking carries "some of the flavour of techno-utopianism" – the belief that technology is the primary way to solve most modern problems.

"Techno-utopians – think Elon Musk – are often captured with the idea of transcending human limits using technology, also called 'transhumanism'," he said.

"They tend to justify potential risk and harm with the promise of progress and discovery of eventual 'solutions'."

Seen this way, some of the more extreme practices and beliefs in the biohacking community – from trying untested methods to rejecting scientific or medical authority – is "a feature, not a bug", said Dr Ang.

This may also explain why the movement appeals to certain groups, such as men in tech.

"The idea that you can master and transcend your bodily limits appeals to masculine sensibilities – think sports, especially bodybuilding – as well as those who have a high degree of control over their lives."

BETTER QUALITY OF LIFE

Indeed, all of the proponents of biohacking who spoke to CNA TODAY were men. And regardless of what anyone might say about their regimens, all of them affirmed that they have noticed tangible improvements in their health since adopting various interventions.

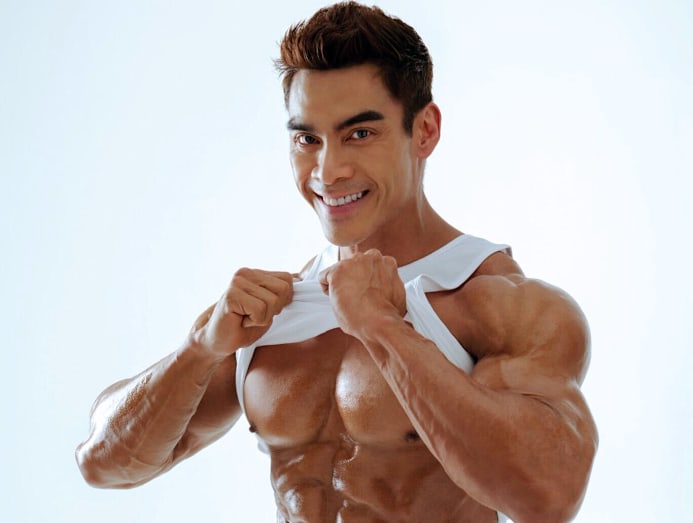

For some, such as Adrian Tan, 49, and Siva Reuben Sreetharan, 53, biohacking is not just about defying age so much as reclaiming health – recovering faster, restoring function and feeling stronger after injury.

Mr Tan, a personal trainer and former competitive bodybuilder who was crowned Mr Singapore twice, turned to biohacking after two surgeries this year for a quadriceps tendon rupture.

His regimen now includes supplements and peptides to speed up recovery. After the surgery, he began undergoing red light therapy almost daily, though he has since scaled it back to once or twice a week.

"Eight weeks after surgery, I was off crutches and I could walk pretty normally. (The recovery) was also quite fast in terms of being pain-free."

He has since continued with these interventions, and Mr Tan said his motivation now is both physical and personal.

"I'm always trying to find ways to push my energy levels up because I'm close to 50. So I look for ways to boost my mitochondria naturally," he said, referring to the tiny structures within cells that act like batteries, generating the energy needed for cells to function.

"When you have access to (these interventions), why not? It's about improving quality of life," said Mr Tan.

Mr Sreetharan's turn to biohacking came after a spinal cord fracture earlier this year left him unable to move his legs fully. The accident happened when he climbed a tree in his garden to remove plastic debris, only for the branch to snap and give way.

His routine now includes daily nutritional supplements and regular sessions in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber. To date, he has completed 60 sessions within a 90-day period.

"The first thing I noticed was that the allergies and skin problems I'd had for two decades disappeared," said Mr Sreetharan.

"The complexion of my skin has improved a lot throughout my arms and the whole body. All those little eczema (patches) on my legs and near the ankles disappeared.

"The neuropathic pains (from my spinal injury) also dropped significantly – it didn't go away totally, but the duration, occurrences and intensity were less."

Mr Sreetharan has since added peptide treatments to his regimen but said he remains cautious.

"I talk to doctors and friends who are doctors, but these are not my attending physicians. They always tell me to be cautious about not mixing certain stuff," he said.

He also tests one intervention at a time, keeping daily notes to track pain, energy levels and mood.

"I don't immediately try anything that sounds fantastic. I do some background work and I do try it in small doses, just to see whether there are any adverse reactions before I even follow the recommended dosage."

Both men said the results of biohacking are tangible: improved energy, better recovery and a renewed sense of agency.

Mr Sreetharan added that biohacking has not only sped up his recovery, it has also helped him emotionally.

"Once the body feels better, the mind also calms down," he said.

"To me, extending life is not really the priority – having quality of life is more important."

PERIL AND PROMISE OF 'DIY APPROACH'

For all the promise of control that biohacking offers – track more, tweak more, live longer – experts caution that the practice crosses into risky territory when enthusiasm overtakes evidence or morphs into obsession.

Dr Laureen Wang, head of the Healthy Longevity Research Clinic and Well Programme at Alexandra Hospital, noted that biohacking often refers to a "DIY approach" to extending one's lifespan and improving healthspan – essentially, taking control of one's biology to boost health, performance or longevity.

"While the intent to optimise health is understandable, in practice, it frequently involves interventions that lack robust, population-level evidence and safety data, often relying on unproven or experimental therapies," she said.

In the private sector, these can include expensive interventions such as peptide infusions, exosome therapies, "young plasma" transfusions, whole-body MRIs that screen asymptomatic individuals, and hyperbaric oxygen treatments.

Many popular interventions, however, still lack large-scale, randomised controlled trials in humans, and robust long-term safety data, said Dr Wang.

"While cellular and animal studies are a crucial first step in research, they are not a substitute for the rigorous human trials required to approve a therapy for public use," she said.

Agreeing, Professor Wang Yibin, director of the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School, cautioned that applying findings from pre-clinical models – studies testing potential drugs or treatments on animals before human trials – to people can be dangerous.

He noted that many of these pre-clinical models are carried out in extremely controlled environments.

“How much of that actually translates to humans needs to be tested through very rigorous clinical studies, including well-designed clinical observational studies or randomised clinical trails," said Prof Wang.

On the risks of obsessively tracking biomarkers and biodata, Prof Wang said that while current scientific literature has identified risk factors linked to ageing-related diseases, the field is still in its early phase – and it remains unclear how reliably these can serve as real-time markers of ageing.

He emphasised that there is still no scientific consensus on any method to tell an individual's precise "health age", or their rate of ageing, from a composite of biomarkers or any biodata.

"Unless you have a person's history, it's really hard, because ageing is a process … (and) not a static state," said Prof Wang.

Those in the biohacking community told CNA TODAY they take care not to tip into tracking-induced anxiety.

Entrepreneur Mr Lin said he avoids using sleep-tracking wearables as they tend to create tracking anxiety, which can lead to unnecessary stress and poorer rest.

While he actively documents his biohacking protocol, the routine he has built has evolved to be "highly flexible and centred around the flow of daily life", he added.

For example, although he administers different interventions at a fixed daily or weekly frequency, he does not keep to a strict schedule.

"I prefer to fit them in whenever I can rather than adhering to rigid timing. I believe being overly structured can be counterproductive, so if I miss a pill, a therapy, or a workout, I don't dwell on it," said Mr Lin.

"I simply carry on and keep the rhythm of balance rather than perfection."

For others trying to separate signals from noise, the experts pointed to simple filters: Be wary of extravagant promises or "one-size-fits-all" fixes, look beyond animal or single-case studies, and seek independent research – with repeatable results – to back up any biohacking claims.

Prof Wang noted that everyone starts from a different baseline, with some already predisposed to conditions such as diabetes, heart, kidney or liver disease. As such, the same lifestyle interventions or supplement protocols cannot simply be copied and applied uniformly to others.

NUS' Prof Ho added that humans are dynamic beings.

"We constantly change over time, and if we are going to design interventions – be it doses or combinations – for people, those have to change with time as well."

Prof Ho said that this means what works for one person won't necessarily work for another – and even what once worked for someone may not always do so.

Since launching his "Delta" study slightly over a year ago, Prof Ho has done about 40 clinical blood draws, as well as microbiome and sleep analyses, and adjusted his trials accordingly.

Even his fasting durations have evolved dynamically – ranging from 18 to 20 hours a day to 48-hour stretches – to study how each variation affects his metabolic efficiency.

As a person's "optimums" shift over time, the effectiveness of any intervention must be continually measured, tracked and adjusted, along with the precision and personalisation of the approach, he said.

Professor Andrea Maier, founder of Chi Longevity and an Oon Chiew Seng Professor in Medicine, Healthy Ageing and Dementia Research at NUS Medicine, emphasised that this "hyper-optimised, individualised management" of nutrition, exercise, sleep and stress remains the strongest evidence-based lever for healthy longevity.

Just as crucial, she said, is ensuring continuous feedback on these interventions – tracking outcomes over time and adapting them to each person's unique biology.

Notwithstanding the ethos of self-experimentation common in biohacking, experts said it is crucial to introduce any intervention in consultation with a medical professional. Without proper medical oversight, even well-intentioned efforts can miss the mark.

As a rule of thumb, individuals should be clear about what they hope to achieve, work with a healthcare professional to decide if those goals are measurable and trackable and finally, monitor their markers to see if the intervention actually works.

According to longevity clinics here, such a personalised, data-driven approach guides their work.

Dr Naras Lapsys, chief clinical officer at Chi Longevity, said clients first undergo a comprehensive baseline assessment – combining blood and urine analyses with functional and physical tests – to build a health profile and identify any deficiencies.

From there, clinicians work with clients to define the outcomes they want, then tailor programmes and personalised interventions to their needs. These may include medical treatments where appropriate, or lifestyle changes, he added.

Having a medical professional involved also helps clients spot potential conflicts in their treatment plan, such as when different interventions might cancel each other out.

Supplement stacks, for instance, remain a point of contention.

"Individual conditions are very different, and how we utilise supplements is a major source of concern," said Duke-NUS' Prof Wang.

"Most of them are probably harmless – but also useless. Yet some, especially in certain combinations and high doses, can be potentially harmful."

REGULATORY SAFEGUARDS

Cautionary tales aside, the promise of self-optimisation remains a powerful draw – and it comes as little surprise that the trend has also taken root here, given the rising concern about ageing in a super-aged Singapore.

Done right, the heart of the biohacking movement can encourage greater health consciousness, as long as it doesn't tip into obsession, experts said.

Prof Maier of Chi Longevity said: "The goal (of biohacking) is not immortality. The real purpose is to maximise healthspan – the years we live free of, or with limited, chronic disease, with vitality and cognitive sharpness.

"Biohacking, when grounded in science, helps individuals take control of that process earlier in life rather than reacting to disease later on."

To ensure it remains safe, experts said setting up an ethics board to oversee the field and regulate private clinics' interventions would be a step forward.

Such scrutiny, the experts said, is still largely missing from Singapore's fast-growing private longevity sector.

As clinics and treatments proliferate, consumers would benefit from an overarching regulatory and ethics board to vet claims and safeguard patient safety, they added.

Prof Wang from Duke-NUS said: "We need to have a more scientific, evidence-based and authoritative view and guidance for our citizens."

He noted that many biohackers adopt certain interventions "with a sincere belief in science".

"But … (they) must rely on proper science to achieve (their goals) – not by extrapolating limited information and applying it in an uncontrolled, unproven manner," Prof Wang said.

Dr Laureen Wang from Alexandra Hospital noted: "Legitimate new treatments follow a specific path. They begin as research in formal clinical trials, which are governed by ethics boards to ensure safety.

"If proven safe and effective over time, they are included in specialty guidelines, and eventually adopted as 'standard of care' by the wider medical community."

Until clearer frameworks are in place, individuals can still take steps to protect themselves, said experts.

Patients should ask questions about the evidence behind treatments, their side effects and how outcomes will be monitored over time. Reputable clinics, they said, will disclose data transparently, conduct proper follow-ups and avoid grandiose promises.

Dr Wang advised consumers to be wary of costly interventions that promise dramatic results, such as reversing ageing.

"The field is driven by commercial hype that often outpaces clinical evidence, leading to high-cost, low-value treatments," she said.

She added that consumers should be cautious of interventions marketed and sold directly to the public before completing proper validation, and of treatments offered commercially that have bypassed rigorous testing or are not yet recognised as standard practice by major medical institutions.

Otherwise, using unregulated supplements or unproven therapies means consumers are essentially running an "n-of-1" – or single-person – experiment on themselves, without oversight or a clear understanding of potential side effects.

NUS' Prof Ho also cautioned people to be wary of the loose – and sometimes "performative" – use of terms such as "optimal" and "evidence-based" in marketing, often with little clarity about what those standards actually mean.

He advised them to ask for peer-reviewed studies, question why a clinic or treatment would yield the same benefits reported in research for them specifically, and find out how safety and efficacy will be monitored over time.

Prof Ho added that a hallmark of sound evidence is repeatability.

"It's important not just to buy into a (one-off) test, but to (understand) how that test or process will be tracked over time to show clear benefits and safety."

There is also value in sharing knowledge among medical professionals, scientists and the biohacking community, he added.

"I try to meet as many people as I can in the biohacking community. I don't think a person loses credibility when they consider themselves a biohacker," he said.

"If we have knowledge – and I have unique knowledge through Delta – of things that can potentially help people, but on their terms … maybe we can together come up with expectations that are safe and achievable so that we don't lose that momentum."

BACK TO BASICS

For now, despite the hype around biohacking, the fundamentals still matter most. Experts say the safest path to "hacking" longevity is unglamorous but well established.

Dr Wang from Alexandra Hospital said it starts with lifestyle fundamentals – regular physical activity, a balanced diet, quality sleep and managing stress early in life.

It also means maintaining strong social connections, practising evidence-based prevention through regular check-ups to monitor and manage risk factors like blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar, and staying consistent in building healthy habits from young.

"It's worth noting that the people in the 'Blue Zone' regions known for longevity and health achieved this without any of these novel interventions," she said.

A Blue Zone, a term popularised by New York Times bestselling author Dan Buettner, refers to a region with a high concentration of centenarians or 100-year-olds. These include Okinawa in Japan, Sardinia in Italy, and Singapore.

Even the biohackers agreed.

Mr Lin the entrepreneur said: "Over time, I realised that much of what we attempt to fix through biohacking can simply be avoided by making better decisions in the first place.

"After sleep, I believe that proper nutrition plays the most important role in overall health and longevity."

Likewise, Mr Moorthy said: "After doing quite a lot of things, I have now come to one of the most important conclusions: Sleep is probably the single most important thing to do. A lot of us tend to ignore that.

"(With biohacking) it sounds like you have to spend tons of money and do this and that, but I think it's really some very important fundamentals first, before anything else."

Above all, Mr Moorthy said that through biohacking, one learns to listen better to one's body – to become more aware of how the body responds to things, and to take responsibility for one's own health.

"It's a lot easier to prevent (illness) than to cure."

He added: "It's going to be very common to live past 100 … but it's not about just living longer. It's about being strong at 100 – not being in a wheelchair.

"You want to be able to do the things that you love, you want to be able to be out in the outdoors. That, to me, is the meaning."

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article misspelt ViewQwest's name as Vieqwest. We apologise for the error.