What’s with the morbid jokes among youth? How to tell when laughter isn’t the best medicine

Dark humour online is helping young adults open up about struggles once kept hidden but experts caution that it can also hide pain that needs care.

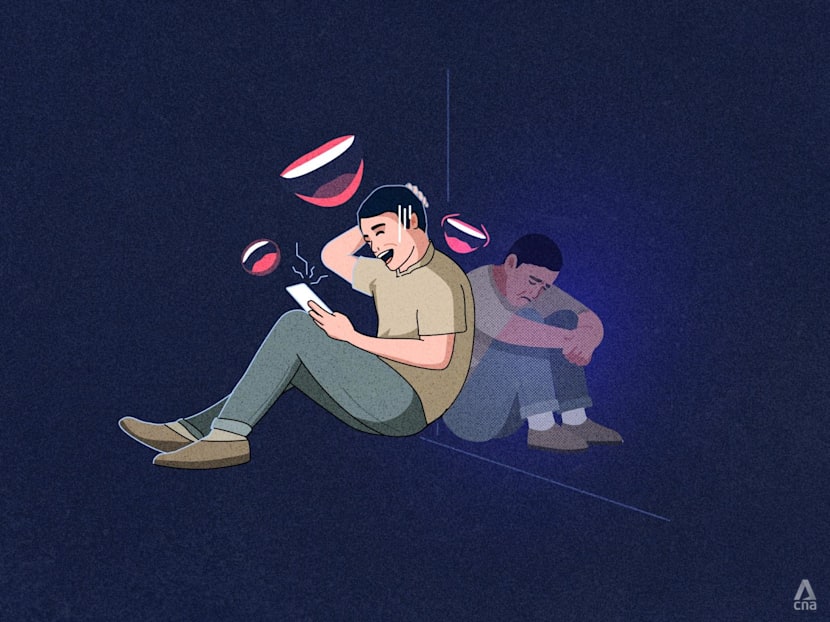

Dark humour backfires when the jokes leave us feeling worse instead of lighter, or when we begin to buy into the hopelessness and helplessness of the situation and struggle to come out of it. (Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Late at night, as I was scrolling through social media as usual, I came across a video. In it, a man is standing at a window of a high-rise block and says, "What if I just – ", before cutting himself off, feinting a jumping motion out the window and then laughing to the camera.

I chuckled at first, then caught myself.

Why did I find that funny? And why did so many others in the comments say something like, "Same … except I'm not joking. Or am I?"

This wasn't a one-off example. In recent years, humour online seems to have turned darker. What once sat in whispers between close friends now lives out loud in memes, chat groups and TikTok videos publicly shared with strangers all over the internet – the feelings of despair or even talk of self-harm.

I've always enjoyed jokes that land a little sideways. I like to think it comes from not taking life too seriously, which was probably why it took me a while to notice when my feed recently began filling up with morbid memes.

But seeing this trend continue on social media, with more people making jokes about serious concerns such as depression or even nuclear war, I find myself wondering: When does this kind of humour help us cope and when does it start to mask the very pain we need to confront?

WHAT IS DARK HUMOUR AND HOW IT CAME ABOUT

Dark humour isn't new. As far back as 1927, pioneering psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud described humour as the way the mind protects itself from painful realities. Psychologists have long noted its role in helping people endure the unbearable.

History offers vivid examples. Under Nazi occupation in the 1940s, Czech citizens used gallows humour to mock their oppressors. In hospital wards today, cancer patients joke about their own mortality as a way to ease tension and reclaim control.

What has shifted is not the existence of dark humour, but its reach.

While every generation has had its own forms of dark humour, it has become more mainstream for younger generations of today because it is more visible to them thanks to social media, Professor Crystal Abidin told CNA TODAY.

The internet culture researcher at Australia's Curtin University described this phenomenon as social steganography, which is where people hide information using context and shared cultural understanding to create a double meaning.

Outsiders may only see despair, but insiders "have the skills and the subtext to be able to decode what is meant there".

The current cultural climate amplifies this.

"We are growing up in very dark times," she said, pointing to how social media collapses news about war, conflict and crisis into the same endless feed as trends, entertainment and personal updates.

And for some people, dark humour doubles as resistance against the pressure to present perfection online.

Instead of curating content or posts about flawless lifestyles, morbid jokes allow for "one-downmanship", where people put their "suffering" in competition with that of others, Prof Crystal said.

"Someone might say I slept six hours and you would go, 'I slept four hours'," she added.

WHO LAUGHS AND WHY

Older generations tend to draw clearer lines on what is acceptable to joke about, but for many young adults, dark humour has become a shorthand for feelings that seem harder to admit out loud.

Ms Stella Ong, clinical counsellor at LightingWay Counselling & Therapy, has observed that her younger clients often use internet memes to describe or process their emotional or mental struggles with "remarkable casualness".

This generational divide can be confusing. Prof Crystal referred to commonplace incidents of parents worrying about cryptic social media posts by their children, only to later discover that they were song lyrics or popular catchphrases.

Without the subcultural knowledge to decode them, adults may misread these posts as cries for help when among their children's peers, they are simply signals of shared experience.

Age aside, various factors may lead people to use dark humour.

Mr James Chong, principal counsellor at The Lion Mind, which offers counselling and psychotherapy services, pointed to situational stress including academic demands, job uncertainty, rising costs of living and constant comparisons on social media.

As a way for people to vent under such pressures without sounding too heavy or risking awkward silence, dark humour becomes a release valve.

Personality plays a role as well. Studies show that those who are more creative and open tend to leverage dark humour more, as well as those who are more highly educated.

However, an issue close to us doesn't necessarily make us more or less likely to crack or enjoy morbid jokes about it.

For some people, distance makes it easier to laugh. For others, it's survival. As Mr Chong the counsellor put it: "If I can laugh at it, it has less power over me."

CAN DARK HUMOUR GET TOO DARK?

When used well, dark jokes are powerful coping tools.

It can even be healthy for us, enabling us to hold two realities at once, Ms Ong of LightingWay said. "I can laugh about this and acknowledge that it hurts," she added.

Lighter jokes may entertain, but dark humour provokes stronger reactions and fosters solidarity through shared struggles by invoking irony or cynicism, Mr Chong said.

Sharing a meme about burnout or despair can be a way of saying "I am feeling this, too" without the heaviness of full disclosure – and in that connection, we can find a brief sense of relief.

Repeated reliance on self-deprecating or morbid humour may slowly shape how a person sees themselves.

However, as with any coping mechanism, there are limits. Overused, dark humour can keep distress hidden, rather than expressed.

It may even damage important relationships or prevent authentic connection, Ms Ong cautioned.

One warning sign is when dark humour stops serving as a release and creates distance instead. "We want to make sure dark humour doesn't become a barrier that minimises genuine suffering or discourages help-seeking behaviours," she said.

Dr Roy Chan, consultant clinical psychologist and founder of the psychology clinic Cloaks and Mirrors, said that people must also be careful not to numb themselves to their own pain.

"Repeated exposure to humour about distress helps to normalise distressing situations, or dull (our) emotional response to triggers that would otherwise be distressing."

Mr Chong cautioned that dark humour backfires when jokes leave us feeling worse instead of lighter, or when we begin to buy into the hopelessness and helplessness of the situation and struggle to come out of it.

Over time, this can even affect our sense of identity.

"Repeated reliance on self-deprecating or morbid humour may slowly shape how a person sees themselves," he said.

Other people may pull away, finding the constant negativity draining and tiring to be around. In the workplace, such jokes can also be misinterpreted as hostility or showing a lack of professionalism.

So, although dark humour may offer momentary relief, overusing it or an overreliance on it risks leaving us stuck, isolated and more vulnerable than before.

STAYING ON THE BRIGHT SIDE OF DARK HUMOUR

As with all things, we need a balance to keep things from tipping.

"The question isn't whether we should use dark humour or not, but rather, if using it helps us live more fully and connect more authentically in life," Ms Ong said.

The mental health experts emphasised that the key to using humour in a healthy way is self-awareness. Ms Ong suggested asking three simple questions:

- Does this bring me closer to or further from the people who matter to me?

- Am I using humour to dodge vulnerability?

- Do I feel more or less empowered afterwards?

If the answers point to distance, discouragement or disempowerment, it may be time to pause and consider other ways of expressing what you are going through.

If it is a friend or loved one you are worried about, try approaching them with curiosity rather than criticism.

Mr Chong advised choosing a private, safe setting and keeping the tone gentle. For instance, you may say: "I've noticed you've been talking about feeling hopeless lately. I know you're joking most of the time, but really, are you okay?"

Even if they brush it off, leaving the door open can make a difference. Saying that "I am here if you ever need to talk more seriously" lets them know support is available when they need it, Dr Chan suggested.

As for keeping the dark side of our own humour healthy, the experts offered three reminders:

- Vary the jokes. Don't get stuck in one mode. Explore lighter humour and make space for serious conversations as well

- Stay mindful. Notice if the jokes help or just keep you stuck. Laughing at the situation, not at yourself, is usually more sustainable

- Hold both truths. Pain and humour can co-exist, and that balance matters more than you think

At its best, dark humour is a bridge, easing the weight of life's burdens. At its worst, it is a barrier, keeping us from facing what hurts and thereby healing from it.

The challenge is knowing which one it is for you.