Singapore aims to tackle high fish mortality rate in nascent aquaculture sector with lessons from Australia

Among the challenges faced by Singapore’s fledgling aquaculture sector is the high fish stock mortality rate, with some farms reporting a rate as high as 70 per cent, compared to Australian farms which face losses typically in the range of 10 per cent or less.

Australian fish farms undertake a more comprehensive regime in monitoring the quality of water that fish are kept in.

PERTH: While Australia has a vastly different landscape from Singapore, it still holds important lessons for the island nation’s nascent aquaculture sector.

Singapore is gleaning insights from Australia's best practices, as it ramps up efforts to help local farmers breed fish more sustainably and fund programmes to better monitor water conditions.

"Good animal husbandry is actually a very key and crucial part of their sustainable operations," said Senior Minister of State for Sustainability and the Environment Koh Poh Koon, who was on a week-long study trip to Southern and Western Australia organised by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA).

Singapore is working to strengthen its food security by producing 30 per cent of its food locally by 2030.

BIOSECURITY TO ADDRESS MORTALITY RATE

Among the challenges faced by Singapore’s fledgling aquaculture sector is the high fish stock mortality rate, with some traditional farms in Singapore reporting a rate as high as 70 per cent, which Dr Koh called a “very high number”.

Australian farms face stock losses typically in the range of 10 per cent or less, he noted.

“I think it speaks to how the business itself needs to actually adopt a science-based approach to animal husbandry, not just to be giving welfare to the animals that they are growing, but also to make sure that they preserve their stock capacity,” said Dr Koh.

The authorities can help provide the resources for local farms to tap on the technical capabilities of veterinary science experts, and adopt better practices that keep the animals healthy and let them thrive well, he added.

To reduce fish mortality rates and prevent diseases, Singapore's fish farms are learning from their Australian counterparts on beefing up biosecurity in their operations.

At the Mark Lee Fish Farm in Adelaide, workers take all necessary measures to keep harmful pathogens out of the water.

Managing director Jack Lee told CNA that it is better to have preventative measures in place, rather than trying to treat diseases after the fish attract them.

“You need to have best practices such as ensuring that the staff when they come into the farm, they are disinfecting all the equipment correctly. They do not have any cross contamination between equipment, you make sure that the equipment that we use for one system does not get used on the other system,” he said.

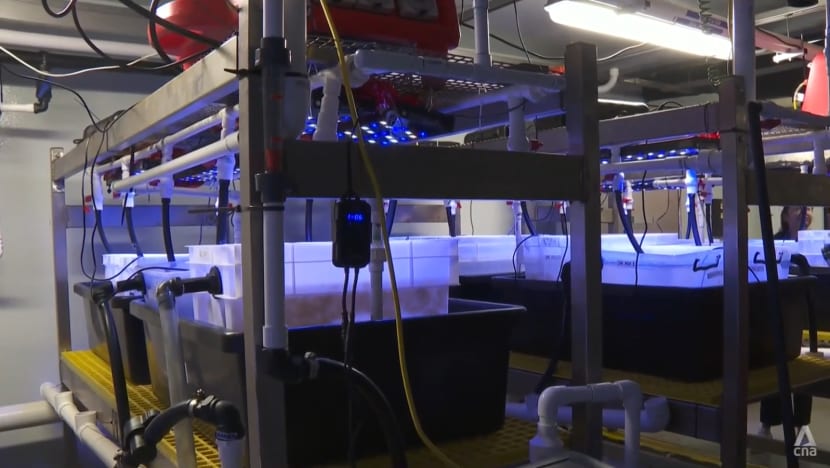

Biosecurity is also equally or even more important in indoor farms.

Clean Seas Sustainable Seafood in Port Lincoln is the largest producer of yellowtail kingfish, a popular seafood in western and Japanese cuisine, outside of Japan.

It supplies 98 per cent of Australia's consumption, but stressed that sustainability is a fundamental part of operations.

“It's not just its quality, but also its sustainability (and) its environmental credentials,” said CEO Robert Gratton. “We absolutely see a future where consumers are going to be increasingly concerned about and aware of the environmental impacts of their consumption decisions.”

Moving forward, the firm aims to use algal oils and insect meals instead of fish oils and fish meals, along with employing multitrophic aquaculture involving seaweed to capture the carbon and nutrient footprint of its farming activities.

Multitrophic refers to the growing of different species in the same place.

Mr Malcolm Ong, founder of The Fish Farmer, told CNA: “Australians want to do things that are one with nature. They try to incorporate what they eat (and) how they live in unison with nature. And the big takeaway that I learned from them is that when they have a problem, they try to find a natural solution to solve the problem.”

He cited the example of using seaweed to absorb excess nutrients in the water, a practice he wants to bring home to Singapore.

Mr Ong added that his farm is working with the National University of Singapore to identify suitable seaweed species for local waters, before testing how best to grow them.

LEGISLATION AND FUNDING

Singapore is also studying how Australia uses a nutrient budget to strike a balance between nutrient content and fish health, said Dr Koh.

“What they have consistently pointed out is that if they have too much dissolved nutrients in the water, it can lead to problems because it means that harmful algae can also grow in there, and that itself can then threaten the fish stock by lowering the oxygen content in the water,” he said.

To ensure the sustainability of a body of water, farmers need to be aware of how much fish are inside and how they feed the fish.

“Some of our farmers use expired bread (and) some put chocolate inside the water to feed the fish as well,” said Dr Koh, adding that some of such products dissipate in the water and end up polluting it with inorganic nutrients.

“It means that actually you don't have a lot more remaining budget of the water to allow the fish to actually grow in there, because the fish contribute some of this nitrogen into the water as well in their waste production."

Because one farmer's feeding practices can affect another sharing the same body of water, legislation may be considered to manage this and level the playing field, forming part of Singapore’s new bill on food safety and security, said Dr Koh.

"Given today's nascent sector, if we do not have some regulations to guide the proper use of feeding and stocking, it may be difficult for the industry themselves to self-regulate so we would have to think about whether we want to put some enabling legislation as a form of guide to the industry to develop themselves sustainably,” he said.

Dr Koh said the authorities will also look closer at funding water monitoring programmes in Singapore’s fish farms.

The authorities currently monitor oxygen levels in the water, and notify farmers when it drops to dangerous levels so they can undertake emergency measures to ensure their fish are not threatened.

“One of the things we learned here is that they do undertake a more comprehensive set of monitoring of water quality, including dissolved nitrogen, nutrients and maybe even other forms of parameters,” he said.

“We will undertake this study with many of our technical agencies and incorporate what the academics and scientific community can bring on board as well, to see how we can roll out a more comprehensive series of monitoring regimes.”