Xi Jinping’s third term: After a decade of building the Belt and Road, where does China go from here?

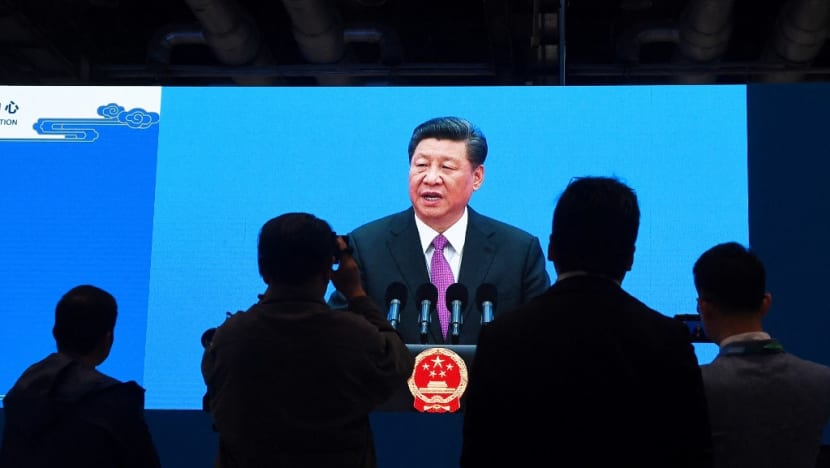

China's President Xi Jinping speaks at a press briefing at the end of the final day of the Belt and Road Forum at the China National Convention Centre at the Yanqi Lake venue outside Beijing on April 27, 2019. WANG ZHAO / POOL / AFP

On Sep 2, two trains for Indonesia's high-speed rail were offloaded at a Jakarta port, marking China’s first export of bullet trains.

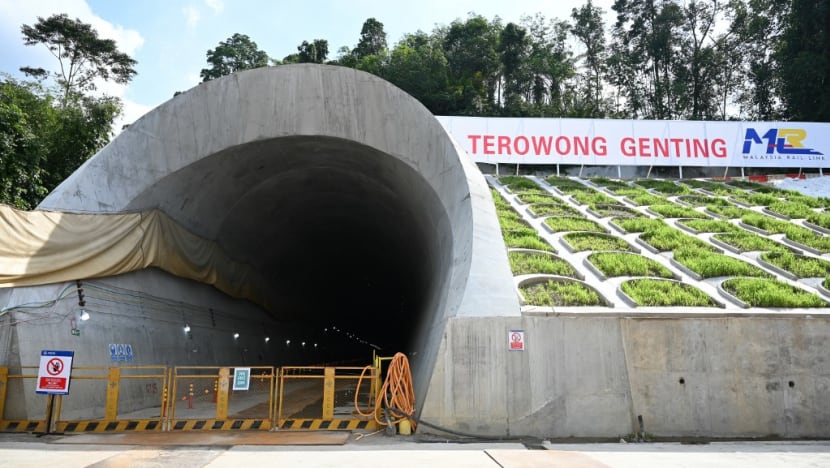

Over in Malaysia, the 640km East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) that stretches across the peninsula is 30 per cent constructed as of May, and on track for the early 2027 completion target.

Up north, the Bangkok-Nong Khai high-speed railway, which links the Thai capital to the Lao border at Nong Khai, is expected to be operational by 2028.

One by one, these pieces are falling into place to potentially form a land corridor. When connected with ports and flanked by infrastructure projects, they will form a massive puzzle known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

First proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 - just a year after he rose to the country’s top post - the BRI comprises an overland trade route spanning China, Central Asia and Europe, as well as a seafaring corridor through Southeast Asia to the Middle East and Africa.

Subsequently, 147 countries signed cooperation memorandums of understanding with China on the ambitious plan. According to financial data company Refiniti, there were 3,220 BRI projects with a combined value of US$3.49 trillion in 2021.

While the BRI has significant strategic implications for China’s growth and global influence, there have been controversies and economic challenges for the countries involved.

The initiative reminiscent of the ancient Silk Road was also unexpectedly grounded by the coronavirus pandemic.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry official was quoted as saying by Reuters in mid-2020 that about 20 per cent of the projects were “seriously affected” and another 30 to 40 per cent were “somewhat affected”.

Fast forward to 2022, pandemic-battered countries around the world are opening up once more but China has remained locked within its borders, which caused its economic growth to slow to 0.4 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter and shrink by 2.6 per cent from the previous quarter.

As China faces pressure to reach the growth target of 5.5 per cent this year, what will likely become of the BRI now and beyond?

BELT AND ROAD A REFLECTION OF XI’S AMBITIONS

The narrative surrounding the BRI says it is an instrument for peaceful co-existence and mutual benefit, matching China’s financial and industrial strengths with the participating countries’ development needs.

Riding on the rise of China from a poverty-stricken country to the world’s second-biggest economy, the initiative symbolises a strong China shaping a new world order.

In Mr Xi’s words, China had reached a new starting point in its development endeavours and was ready to steer a new normal of economic development.

“We will actively promote supply-side structural reform to achieve sustainable development, inject strong impetus into the Belt and Road Initiative and create new opportunities for global development,” he said at the opening ceremony of the Belt and Road Forum in May 2017.

In his vision, the BRI is a “road of prosperity” supported by industrial cooperation, financial systems and infrastructure connectivity.

The enormous scale of the BRI is a reflection of Mr Xi’s confidence and ambition in claiming global pre-eminence, and this still holds true a decade later.

“I think Xi Jinping, like any other world leader, would want to create his own legacy,” said Dr Nur Shahadah Jamil, senior lecturer at Universiti Malaya’s Institute of China Studies.

“Being labelled as China’s ‘strongman’ after Mao Zedong, Xi has proven himself as a different kind of Chinese leader.

“Through his constant consolidation of power within the party and the country’s political system, he has showcased his ambition and growing confidence by pursuing the BRI at the world stage - which none of his predecessors or other countries has embarked on,” she said.

For China, the BRI marked a departure from Deng Xiaoping’s “taoguang yanghui (keeping a low-profile)” strategy to “yousuo zuowei (accomplish something)” strategy, Dr Nur Shahadah said.

“Thus, one may notice that Xi’s style is more proactive and confident,” she said.

However, there has been scepticism about Beijing’s motives.

“Why is China so nice to us?” is a common question posed to the Chinese hosts during academic exchanges, shared Professor Cheng Ming Yu, chairperson of the Belt and Road Strategic Research Centre at Malaysia’s Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR).

And China’s reply is simply, “For win-win development.”

“‘Only when you grow, then we can grow. We have to grow together,’” Prof Cheng said.

“China cannot prosper if people cannot buy what they produce. It’s better to make other countries develop at the same time, then China can transfer its technology and continue to sell its products.”

CONTROVERSIES AND CRITICISMS

With an emphasis on infrastructure connectivity and unimpeded trade, the BRI has the potential to substantially improve trade, foreign investment and living conditions for people in participating countries, a World Bank study in 2019 suggested.

With the infrastructures in place, travel times could reduce by up to 12 per cent along the economic corridors, while that with the rest of the world was estimated to decrease by an average of 3 per cent.

Trade would also increase between 2.8 and 9.7 per cent for Belt and Road corridor economies and between 1.7 and 6.2 per cent for the world, the study added.

The caveat, though, was that China and the countries have to adopt policy reforms that increase transparency, expand trade, improve debt sustainability as well as mitigate environmental, social and corruption risks.

According to the report, one-quarter of the Belt and Road economies already have high debt levels, and medium-term vulnerabilities could increase for a handful of them.

China critics have long described the initiative as a debt trap that drowns countries in unsustainable debt as Beijing wields undue influence over them, not to mention sovereignty and security concerns.

In Malaysia, the then Pakatan Harapan government suspended the ECRL and two Sabah gas pipeline projects in July 2018, citing national interests.

Then prime minister Mahathir Mohamad said in August 2018: “The project will not go now, because we don’t need them at the moment. Our priority is reducing our debts, if we are not careful, we could be bankrupt.”

The ECRL later resumed after the government negotiated with China to bring down the costs by RM21.5 billion to RM44 billion, while the gas pipeline projects were revived in February 2021 by the new government.

Elsewhere, countries like Pakistan, Myanmar, Maldives and Nepal were also reconsidering the terms of their BRI participation, Moody noted in a June 2019 report.

Beijing has rejected the debt trap claim. It is “a lie made up by the United States and other Western countries”, said Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin in an August press conference.

One should not simply put the blame on one party for unsustainable or failed projects, said UTAR’s Prof Cheng.

“It’s very much a governance issue and cannot be blamed totally on the BRI,” she said.

“In business projects, there are investors and there are hosting countries. It depends on how you negotiate and how you carry out the projects.”

She opined that BRI has been used as a political weapon, which resulted in other aspects being sidelined. Focus should be on the impact and how to benefit from the initiative’s connectivity essence, she added.

SIGNS OF SLOWING DOWN

It has been almost a decade since the BRI was conceptualised, and Prof Cheng is of the view that the first phase of the BRI - with a focus on mega projects laying down the infrastructures - is almost coming to its end.

The next phase is about building soft infrastructure.

“Focus may not be so much on spending money like before, not on the type of projects and scale,” she said. “It will branch out to other aspects - such as the health, green and digital silk roads - different aspects of development using the same BRI concept.”

A report published in 2022 by data analytics provider Refinitiv noted that the BRI was going through a recalibration process.

With COVID-19, China has spent much of the last two years helping its BRI partners, offering Chinese vaccines, personal protective equipment and health equipment to African, South Asian as well as South American countries. It is also working on joint vaccine production with nearly 20 partner countries and providing vaccine financing via the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, it said.

While there has been a steady development of BRI projects since the pandemic, engagement will be lower for the second half of 2022 and in the near future, said the deputy research director at Malaysia’s Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS) Sri Murniati Yusof.

She was referencing a report from the Green Finance & Development Center at Fudan University’s Fanhai International School of Finance, which indicated that the slower pace came after the decision by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce to stop fast overseas expansion.

“I also want to add that slower expansion may also be influenced by the domestic economic situation in China and slightly stricter requirements by the Chinese government for Chinese overseas investors.

“Since the end of 2021, the Chinese government has put more efforts into integrating sustainable development, particularly environmental sustainability in BRI projects through its BRI Green Development Coalition,” she said.

In September last year, Mr Xi announced at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) that Beijing will not finance new coal-fired power projects abroad.

Two months later, the Communist Party’s central committee pledged to place greater importance on making BRI cooperation greener and more sustainable, according to Xinhua.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR THE BELT AND ROAD

Hailing “tangible and substantial progress” in cooperation between China and participating countries, Mr Wang, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson, said in August: “Going forward, China will continue to make new and solid progress in high-quality Belt and Road cooperation with all parties.”

What can the world expect from Mr Xi on advancing his pet project, as he looks set to secure a fresh term in office during the Communist Party congress this month?

A rebranding of BRI is on the cards, noted Dr Nur Shahadah of the Institute of China Studies as she drew attention to the Global Development Initiative proposed by Mr Xi at UNGA last year.

“According to Xi, the focus will be set on ‘people-centred development’ by concentrating on helping poor nations recover in the post-pandemic era through international development cooperation.

“I think this initiative is a rebranding or repackaging of BRI, but it covers wider aspects and scope, including the field of digital economy or green economy,” she said.

BRI’s importance in China’s global strategy will stay and its global reach will likely expand gradually, said Min Ye, an associate professor of international relations at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University.

That being said, BRI faces three significant hurdles, she told CNA.

The first hurdle is concerted competition from advanced democracies in infrastructure, financing and diplomacy. And the second is intractable recession induced by the pandemic in many countries.

“Third, China’s domestic economy is facing a headwind, and Chinese companies and investors will be less capable and interested in global expansion,” she said.