Debate rages in Indonesia over appointment of active military personnel to civilian posts amid bribery probe

Headquarters of the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission in Jakarta, Indonesia. (Photo: CNA/Wisnu Agung Prasetyo)

JAKARTA: Indonesian analysts and activists have lambasted the country’s anti-corruption commission after the body handed over a high-profile case involving two senior military officers to the armed force’s military police.

The move has sparked concerns of leniency shown towards the two suspects due to the opaque nature of the legal processes inside the armed forces, and also intensified calls for President Joko Widodo to stop appointing active military officers to non-military positions.

The controversy stems from the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK)’s move on Wednesday (Jul 26) to charge National Search and Rescue Agency (Basarnas) chief Henri Alfiandi for his alleged involvement in an 88 billion rupiah (US$5.8 million) bribery case.

The charges came after the commission conducted a sting operation on last Tuesday during which several people were apprehended, including Basarnas’ administrative staff coordinator Afri Budi Cahyanto.

Both Alfiandi and Cahyanto are active members of the Indonesian Air Force. The former is an air marshal - a rank equivalent to a lieutenant-general - while Cahyanto is a lieutenant-colonel.

The three other suspects, the KPK said, were civilian contractors who have been awarded contracts by Basarnas since 2021 to procure devices that can detect and locate survivors trapped underneath rubble.

The commission’s decision to charge Alfiandi and Cahyanto drew criticisms from the armed forces which insisted that the KPK had overstepped their jurisdiction by laying criminal charges against active military officers.

On last Friday, the KPK agreed to hand over the cases against Alfiandi and Cahyanto to the military police while the anti-graft body would focus on three civilian contractors suspected of providing bribe money to the pair.

Related:

The KPK also issued an apology to the military for slapping corruption charges against the two officers.

“We understand that our investigators may have been in the wrong and forget that whenever (a) military (officer) is involved, (the case) should be handed over to the military. We shouldn’t be the one handling it, not the KPK,” the anti-graft agency’s deputy chairman Johanis Tanak told reporters last Friday.

The KPK’s move immediately drew criticisms from activists and experts.

“The KPK has destroyed its own credibility by apologising. The move was uncalled for and inappropriate. They have the right and should pursue this case to be tried in a (civilian) anti-corruption court,” Mr Al Araf, chairman of security and human rights research group Centra Initiative, told CNA.

Meanwhile, the move has also created a rift inside the KPK with investigators and staffers criticising their superiors’ decision to hand over Alfiandi and Cahyanto. Local media reported that move has even led one senior KPK investigator to submit his resignation.

Some NGOs are calling for a cessation in the practice of appointing active military officers to non-military positions.

“The government must evaluate the presence of active military officers in a number of civilian institutions … because it will only create legal controversies whenever a crime involving these active military members occurs,” Mr Gufron Mabruri, director of human rights advocacy group Imparsial, told CNA.

OVERLAPPING JURISDICTION

The military argued that it retains the sole right to investigate and prosecute an active military officer in Indonesia, something which Mr Agus Sunaryanto, coordinator of non-for-profit organisation Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), disputed.

Sunaryanto said the 2004 law governing the KPK provides the anti-graft body with the authority to investigate and prosecute a military officer as long as the act of corruption is allegedly committed together with ordinary civilians.

However, the law on military court states a military officer must be prosecuted in a military court. The law was enacted in 1997 and has never been amended.

To accommodate the two conflicting laws, Mr Sunaryanto said the KPK can request for the formation of the so-called “koneksitas” court, an ad-hoc tribunal consisting of civilian and military judges.

“The KPK has never used this authority, and it’s time they should,” he said.

In a video uploaded to his personal Instagram account on last Saturday, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Politics, Legal and Security Affairs Mohammad Mahfud Mahmodin asked everyone to stop arguing who has the right to prosecute the two military officers.

“What matters is what comes next, which is for the law to be enforced against the heart of matter,” he said, adding that he supported the KPK’s move to hand over the case to the military.

President Jokowi, as he is popularly known, told reporters on Monday that he would stay out of the apparent tug-of-war between the KPK and the military as he urged the two bodies to work together.

“I think it is just a matter of coordination. Coordination must be made by all institutions according to their respective capacity based on rules and regulations,” he said.

But Mr Al Araf of research group Centra disagreed, saying that the military court does not have the same capacity and credibility to prosecute corruption cases as its civilian counterpart.

“There have been many examples of military officers receiving lenient sentences for crimes such as human rights violation, murder and corruption when tried in a military court,” he said.

Mr Al Araf said there is little transparency in a military legal process, with investigation outcomes rarely made public and court hearings largely off limits to the media and ordinary civilians.

“A military court does not meet the standards of a fair trial and often results in injustices for the victims and the public at large,” he added.

MILITARY PROMISES PROFESSIONALISM

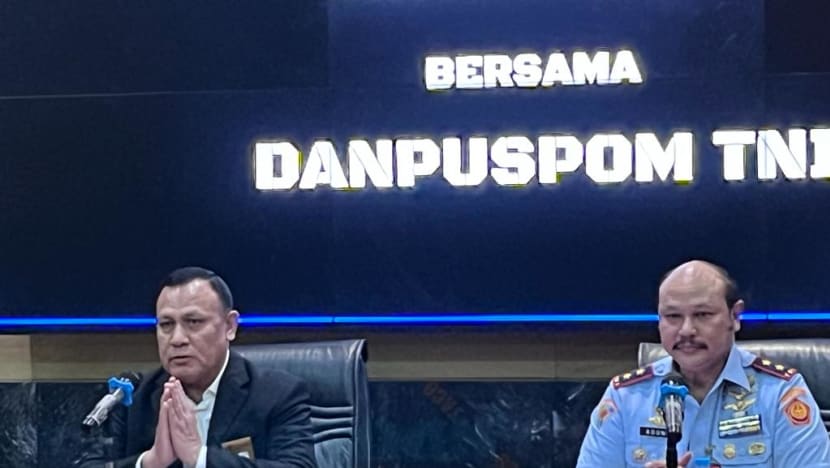

During a press conference on Monday, military police chief Agung Handoko promised that the military would investigate the bribery allegation professionally.

“Chief of the Armed Forces (Yudo Margono) has firmly instructed that all soldiers violating (the law) should be punished. The military is committed to eradicating corruption,” the two-star Air Force Vice-Marshal said.

The military, Mr Handoko said, has invited the KPK to assist with the investigation, particularly since it involves witnesses and pieces of evidence in the anti-graft body’s custody.

“The military chief has instructed that coordination and synergy with the KPK must be maintained for cases involving military personnel,” he said.

Mr Handoko said Cahyanto had confessed to receiving what the corruption suspect described as “commando money” from several contractors which were awarded with the project.

He added that Cahyanto had told investigators that he was acting on the instruction of the Basarnas chief Alfiandi, adding that he always reported to the latter how much money was received from the contractors.

At the time of his arrest last week, Cahyanto had just received close to one billion rupiah (US$66,282) from one of the contractors, said Mr Handoko, adding that Alfiandi was still being questioned as of Monday evening.

The military police chief said both Alfiandi and Cahyanto will be tried in a military court despite the former, who celebrated his 58th birthday on Jul 24, recently reaching retirement age.

“The legal process will apply according to (Alfiandi’s) status (as an active military office) when the alleged crime occurs,” he said.

MILITARY PRESENCE IN CIVILIAN POSTS CRITICISED

The president has promised to review the assignment of military personnel in civilian institutions.

“All (positions) will be evaluated, not just the problematic one, all of them,” he said on Monday.

With Alfiandi in military police custody and entering retirement, Armed Forces chief Yudo Margono has appointed Air Marshal Kusworo as the new Basarnas chief.

Mr Kusworo, who like many Indonesians goes by one name, began his new position on Monday.

Since it was founded in 1972, Basarnas has always been led by an active military officer from different branches of the Armed Forces, despite being a civilian government institution.

The 2004 law on the Indonesian Armed Forces only allows active military personnel to occupy positions in 10 non-military institutions and agencies, including the Basarnas.

Related:

An amendment to the law is currently being deliberated in parliament, and there are suggestions by some politicians that this number should be increased.

Experts and activists disagreed, however, saying that it should be reduced instead.

“Basarnas is not a military agency. It is not related to defense or national security. So why should it be headed by an active military officer, especially given the fact that the military seems to think that civilian law does not apply to them?” Mr Al Araf of Centra Initiative said.

Mr Abdul Fickar Hadjar, a criminal law expert from Jakarta’s Trisakti University, said as long as active military officers remain untouched by civilian court, members of the Armed Forces should stay clear from civilian posts.

“A military officer working in a civilian institution should be temporarily suspended from their status as an active military personnel. That way they will be completely subjected to civilian law, including the law on corruption,” Mr Hadjar said.