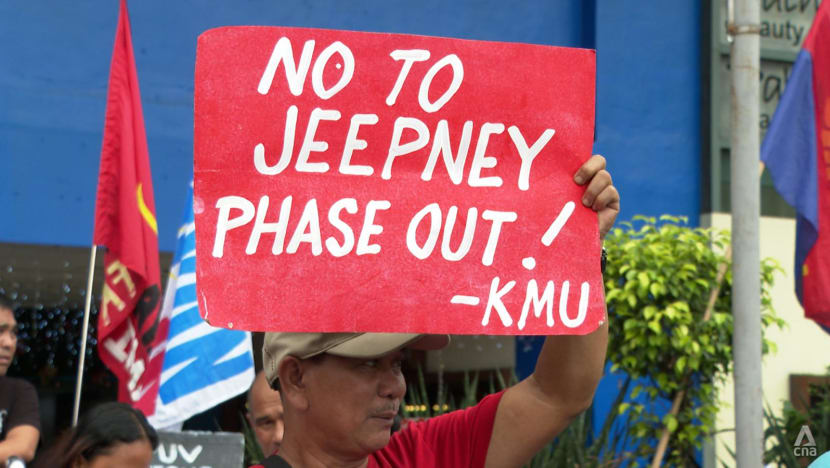

Fears of losing livelihoods mount as Manila’s jeepney drivers protest phase-out of iconic vehicles

Dubbed as the country's “King of the Roads”, jeepneys serve as an icon of Philippine culture. They evolved from World War II-era open-air combat vehicles left by the Americans to the then-US colony, but were modified for civilian use to accommodate more passengers.

The Philippines government plans to eventually phase out old versions of the country's iconic jeepney, and replace them with more modern vehicles.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

METRO MANILA: Transport groups in the Philippines are protesting against the government’s plans to eventually phase out old versions of the country's iconic jeepney.

The government had set a Dec 31 deadline for jeepney operators to surrender their franchises and consolidate into cooperatives, but activists have petitioned the Supreme Court to stop the move.

The plan is to phase out traditional jeepneys that are 15 years old or older and replace them with imported minibuses that produce less emissions.

A locally built prototype of a more modern vehicle retaining the traditional jeepney’s design has also been developed, but cooperatives that complied early with the Public Utility Vehicle (PUV) modernisation programme have gone ahead to purchase the new minibuses through bank loans.

There are concerns that the looming consolidation could put thousands of drivers and operators out of work if they do not join a cooperative, while also raising transport costs.

Proponents of the modernisation programme have argued that granting franchises to operate PUVs, which is a form of public service, is a matter of state discretion.

However, jeepney owners opposing the move have noted that their freedom of association guaranteed by the Philippine Constitution includes the freedom to opt not to associate, and that the modernisation programme forcibly makes them join a group or lose their small enterprises.

Dubbed as the country's “King of the Roads”, jeepneys serve as an icon of Philippine culture.

They evolved from World War II-era open-air combat vehicles left by the Americans to the then US colony, but were modified for civilian use to accommodate more passengers.

With their varied routes and low maintenance costs, jeepneys became the preferred mode of transportation among the Filipino working class.

Unmaintained jeepneys contribute to Manila's air pollution, but owners who operate jeepneys that comply with local emission regulations say it is unfair to generalise the vehicles.

ARRIVAL OF MODERN JEEPNEYS

Under the government's current plan, cooperatives would be granted franchises to operate fleets of the new minibuses dubbed as "modern jeepneys", which will cost them more than US$43,000 each.

The starting fare for the modern jeepneys is 2 pesos (US$0.04) higher than the rates of traditional jeepneys.

The modern versions come with air-conditioned travel, more spacious seating, and security features like multiple closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras.

One cooperative currently running a fleet of modern jeepneys pays jeepney owners nearly US$6 a day for each traditional jeepney turned over to be scrapped.

For each old vehicle scrapped, the cooperative can add a modern jeepney purchased through a bank loan to be paid over seven years, with the government subsidising about 11 per cent of the cost.

The subsidy goes straight to the cooperative as capital shares of the jeepney owner, who transitions from being a small enterprise owner to a cooperative investor.

Some jeepney owners who drive their own vehicles can also receive additional daily pay in a cooperative by becoming the driver of a modern jeepney unit.

Pandacan Transport Cooperative chairman Edmundo Cadavona told CNA a collective arrangement is better for jeepney operators, as they no longer need to worry about maintaining their vehicles.

“The new vehicles are safe, comfortable, air-conditioned and produce less emissions with their Euro 4 engines,” Mr Cadavona said.

TRANSITIONING TO THE FORMAL SECTOR

Drivers who do not own jeepneys are hired by cooperatives with fixed daily salaries, as opposed to the profit-sharing scheme of traditional jeepneys, essentially transitioning them to the formal economy.

The cooperative also remits directly to the state each driver’s monthly premiums for their social security and state health insurance. The amount is paid by employers and salary deductions.

However, many traditional jeepney drivers who live hand to mouth remain sceptical, as they feel the amount of take-home pay is better under the traditional scheme.

The social security benefits of a traditional jeepney driver are paid voluntarily, if at all, with many retiring with no pension.

Others in the informal economy who make a living through the popular form of transportation are similarly worried. These include workers who call out for passengers, known as “barkers”, or who help to park the vehicles, known as “starters".

Mr Elmer Cordero, who has been a jeepney driver for most of his life, told CNA: “We call on the president to prioritise the poor and not foreign countries.”

The modern jeepneys are imported from other Asian countries.

Mr Cordero, 75, is a member of leftist transport group PISTON that filed the petition before the Supreme Court.

He used to be a casual member of the group, until a ban on jeepneys during the pandemic forced him to protest, for which he was jailed.

COSTS AND COMFORT

For commuters of the modern jeepneys, the air-conditioning is the main draw.

Non-commuters have also started using public transport following the arrival of the more comfortable modern jeepneys, especially on routes with shorter travel durations. Route rationalisation is also part of the PUV modernisation programme.

“The modern jeepney in this route passes by our house. It is very convenient. There is an air-con. It is refreshing,” said passenger Wenzy Calubuyan.

Ms Calubayan said she has never taken a ride on a traditional jeepney, and would otherwise not use mass public transportation if not for the modern versions.

However, passengers who commute on traditional jeepneys remain anxious about having to fork out more for their rides, especially if the modern jeepneys increase their fares further down the road.

“That small fare margin between modern and traditional jeepneys still hurts commuters, especially low-wage earners,” commuter Kaiza Joy Aquino told CNA.

Ms Aquino said she is concerned for minimum-wage earners and workers of micro-enterprises who sometimes earn below the regional minimum wage.

“In cities, you ride jeepneys multiple times to get to your destination. The fare increase (hence) piles up,” she said.

SUPPORTING THE INFORMAL ECONOMY

Small-time jeepney operators said they are at a loss as to how to start a cooperative, as they have received little support and information from the government.

They also fear losing money to corrupt or mismanaged cooperatives.

Many drivers and owners told CNA that the amount they take home now is more than what they are likely to earn if they join the cooperatives.

“The modern jeepneys will be owned by the cooperative, not us. We would just be employees, so we don’t like the programme,” said one operator.

Another jeepney owner told CNA that if he has no choice and is forced to give up his small businesses, he would join a cooperative so that he can afford to send his children to school.

One driver said: “If they phase out jeepneys, many will lose their livelihood and starve. Many drivers are 40 to 70 years old.”

Jeepney drivers also support small sidewalk eateries and stores selling ready-to-eat snacks and coffee at jeepney terminals, one of which is run by Mr Cordero.

Many cooperatives have their own canteens as additional income sources.

Older workers, such as Mr Cordero who has no pension and has to pay for rent and food on a daily basis, say they are unlikely to be hired by cooperatives due to their age.