New Delhi’s land is sinking rapidly – and scientists say the risks are on the rise

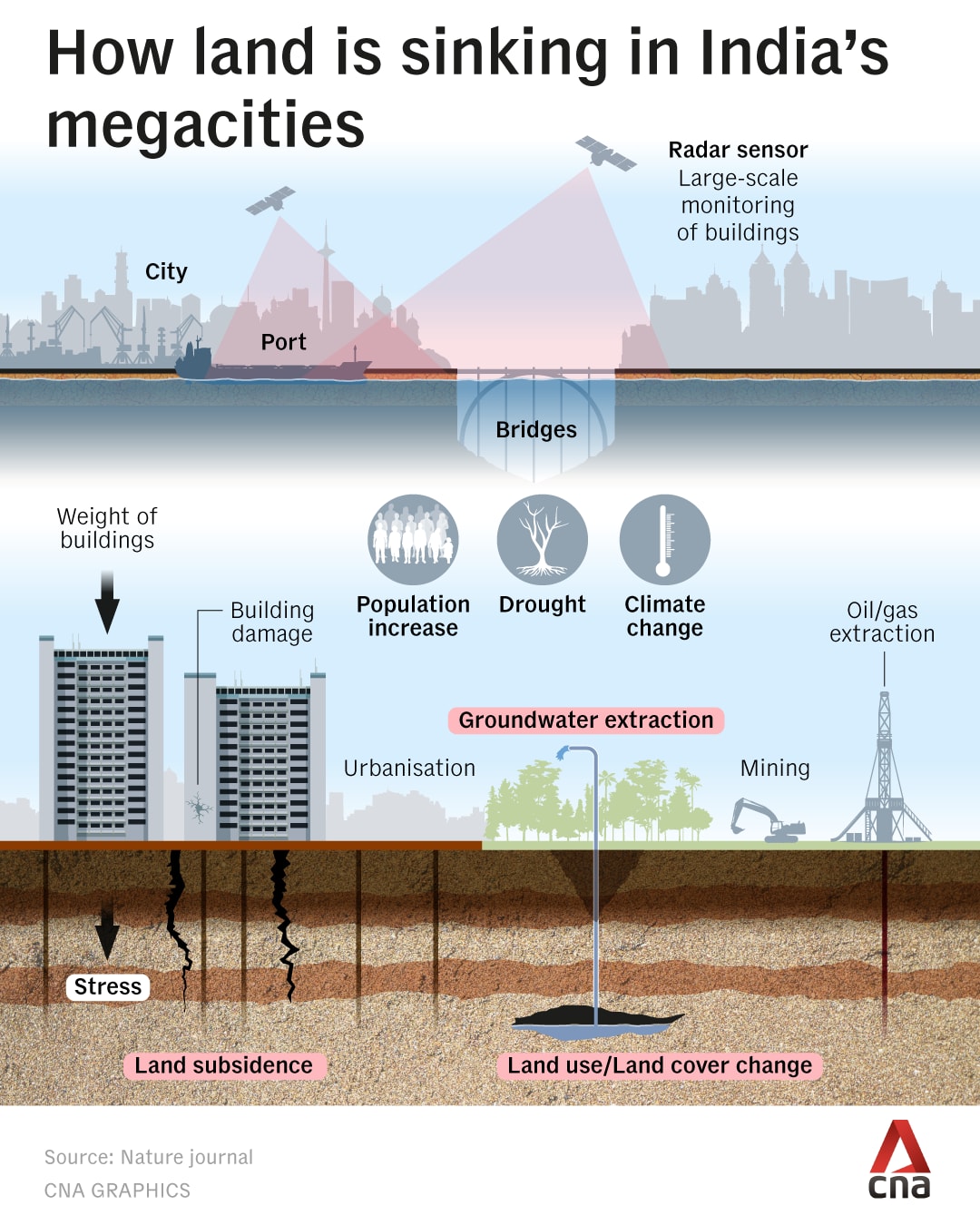

Researchers have tied the problem to widespread over-extraction of groundwater, particularly in lower-income neighbourhoods where piped water is scarce.

A crack that formed on the wall of a building in New Delhi, due to land subsidence.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

NEW DELHI: When cracks first appeared on a pillar supporting a 12-storey residential building in New Delhi, just a few kilometres from India’s busiest airport, Rajesh Gera and his team assumed an earthquake had struck.

But the president of the Surya Vihar Resident Welfare Association, which manages the building, was mistaken.

Researchers studying land subsidence proposed a more troubling theory – the crack was a symptom of the city buckling under its own weight.

SINKING HOTSPOTS

Parts of New Delhi, especially near the Indira Gandhi International Airport, are sinking at a rate faster than any other Indian megacity, largely due to massive groundwater extraction.

The findings were published this year in the leading multidisciplinary science journal Nature, by researchers from India, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States.

They pinpointed three sinking hotspots – all located within 12 sq km of the airport.

The researchers, who examined satellite radar data from 2015 to 2023, found that up to 878 sq km of urban land across five major Indian cities is subsiding, with New Delhi among the worst affected.

These five fast-growing megacities – New Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Chennai – house a population of 83 million in total.

Satellite data suggests that the land below New Delhi and surrounding areas is subsiding by 11cm every year – roughly the length of a smartphone.

More than 2,200 buildings within an area of 100 sq km in India’s capital are at risk of structural damage. If subsidence continues at the current rate, 11,000 buildings will be at risk within 50 years.

TICKING TIME BOMB

Researchers have tied the rapid sinking to widespread over-extraction of groundwater, particularly in lower-income neighbourhoods where piped water is scarce and underground wells are running dry.

As water is pumped out of the cracks and spaces beneath the Earth's surface, the soil slowly compresses into cavities, causing the land to subside.

With a city of 30 million people on top of this fragile land, the consequences become more severe.

The problem is also becoming a ticking time bomb due to New Delhi’s vulnerability to earthquakes.

“When an earthquake happens … the building kind of sways. Coming back to the cavity below, due to the land subsidence, the building will also start to move. This can actually uproot a building,” said Vikas Kanojia, principal architect at New Delhi-based design firm Studio Code.

“It can be that kind of devastation if Delhi experiences an earthquake of magnitude of 5.”

RESIDENTS FIGHT BACK

Some are refusing to wait for a disaster to happen.

In one neighbourhood in New Delhi’s Dwarka area, some residents have invested thousands of dollars to install rainwater-harvesting pits, reviving a centuries-old water body in the area and helping to recharge local aquifers.

As groundwater levels slowly recover, researchers tracking the city's subsidence said the land there has begun to rise again.

Sudha Sinha, one of the residents who pitched in, said the water situation has been improving over the past five years.

The former president of the Cooperative Group Housing Societies Dwarka added: “The people who are … staying here have stopped using groundwater. The adjoining areas – they're still using the groundwater."

Researchers say these grassroots efforts may offer one of the few viable paths forward if the soil is to stabilise.

WARNING SHOT FOR URBAN PLANNING

Experts are calling on authorities to make smarter choices about where cities expand.

They urge designating high-risk zones – particularly where soil naturally tends to sink – as no-build zones.

Combined with stricter groundwater regulations, improved surface-water supply and mandatory rainwater harvesting, such measures may help slow down or even reverse the sinking, they said.

For many in New Delhi, the cracks in pillars and shifting walls are no longer just structural issues – they are signs that the ground beneath their homes may not hold for much longer.

At the housing complex looked after by Rajesh Gera, cracks have now formed across the floor.

“We try to be strong, put on a brave face, but when we think deeply about this, there’s always a fear that this can cause a big catastrophe,” Gera said.

“As individuals, there's not a lot we can do about it. The Indian government and the Haryana state government need to study this. Otherwise, this can become a big problem,” he added.