Indonesia moves to tackle issues of food waste and malnutrition among some children

Despite the country's large amount of food waste, stunting, a condition of impaired growth and development in children due to malnutrition and poor hygiene, remains a problem.

More than half of the waste at this landfill in Bantargebang, a landfill southeast of Jakarta, is made up of leftover food.

INDONESIA: At a landfill that collects most of Jakarta’s waste, piles of trash can reach dizzying heights – 40 metres, or as high as a 12-storey building.

Much of it - more than 50 per cent - of the waste at Bantargebang, a landfill southeast of the capital, consists of leftover food, according to research by the Jakarta Environmental Agency. Jakarta produces more than 7,500 tonnes of trash daily and most of it is sent to this site.

The numbers, however, are not a surprise, given the findings of a recent government report.

The report by the National Development Planning Agency that looked at 20 years’ worth of data showed that 23 to 48 million metric tonnes of food was dumped every year from 2000 to 2019, translating to between 115kg and 184kg of food per capita per year.

Food waste costs the country between US$14-40 billion a year in economic losses, or up to 5 per cent of Indonesia’s GDP.

The country faces another issue related to food, with some children sufferings from stunting, a condition of impaired growth and development due to malnutrition and poor hygiene. While Indonesia’s national stunting or low height-for-age prevalence has declined from 27.6 per cent in 2019 to 24.4 in 2021, the country wants to improve these figures.

MITIGATING THE FOOD WASTE PROBLEM

Efforts are under way to tackle both problems.

When it comes to food waste, among the solution finders is FoodCycle Indonesia, a food bank that distributes surplus food items from sources such as wedding parties, bakeries, corporate lunches and supermarkets.

The organisation helps to feed about 120,000 people every year, but its general manager Cogito Ergo Sumadi Rasan said more needs to be done.

“The biggest challenge is actually to convince, to encourage many parties to get involved in this. Because when asked to donate food, especially food that is edible, they are sometimes worried,” he told CNA.

“Corporations are worried that their brand could be negatively impacted if they give away food that they think is not edible, even though it still very much is safe to eat.”

One such firm that had similar concerns, but decided to reduce its food wastage is McDonald’s.

Food on display past its allocated holding time is usually thrown away, But now, as part of its food rescue programme, items like muffins and fried chicken are collected twice a day and donated.

Before collaborating with FoodCycle Indonesia, the firm ran tests in a laboratory on whether the food is suitable to be given away, said Ms Sutji Lantyka, associate director of communications at Mcdonald’s Indonesia.

“Then we decided that it was, after the tests yielded positive results and (showed that) the food still has good nutrition,” she said.

Beyond reducing food wastage in this way, head of Jakarta Environmental Agency Asep Kuswanto highlighted where more can be done.

“In the future there will be an NGO or friends from NGOs who will help to save the food at the very least - for example, rice. White rice, which has a lot of leftovers, will be processed into fried rice, which we can distribute later to various foundations, to various members of the community who need it,” he said.

THE STUNTING PROBLEM

At the other end of the food problem is stunting, which is the result of chronic or recurrent undernutrition. It is usually associated with factors like poverty, poor maternal health and nutrition and inappropriate feeding and care in early life according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Stunting is a bigger problem in some areas of Indonesia compared with others.

Stunting prevalence in East Nusa Tenggara province reached about 38 per cent in 2021, the country’s highest according to a government survey. This is higher than the national figure and almost double the 20 per cent tolerance limit set by the WHO.

Stunting prevents children from reaching their physical and cognitive potential, WHO said.

The availability of food may not be the problem in East Nusa Tenggara province - Indonesia’s National Waste Management Information System shows that food constitutes nearly 35 per cent of waste there.

It is deep-rooted parenting practices alongside poor sanitation and access to food that stand in the way of providing children with a healthy environment and nutritious food, said health workers on the ground.

“Based on our mapping of the stunting problem, the issue is not the wasting of food in families but the prioritisation of fund allocation,” said Ms Caecilia Tyas Wurina, nutrition officer at Labuan Bajo Health Centre.

She gave the example of a family that has limited money, which goes to buying items like cigarettes and coffee if they already have a supply of rice, so children end up having rice with coffee as a meal.

FINDING SOLUTIONS TO THE HEALTH ISSUE

The country is looking to reduce stunting prevalence to 14 per cent by 2024. Both the government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are trying to change the situation.

Indonesia’s National Population and Family Planning Board is working to raise awareness with a collaborative effort, an information system and prioritising providing for those who are vulnerable to stunting.

Between ministries and institutions, between agencies, between institutions in the village, the challenge is uniting all parties to eliminate sectoral egotism said the head of the agency Hasto Wardoyo.

“We try with convergence, we try to create a common enemy. Our enemy is stunting. It is also necessary to have a change of behaviour,” he said.

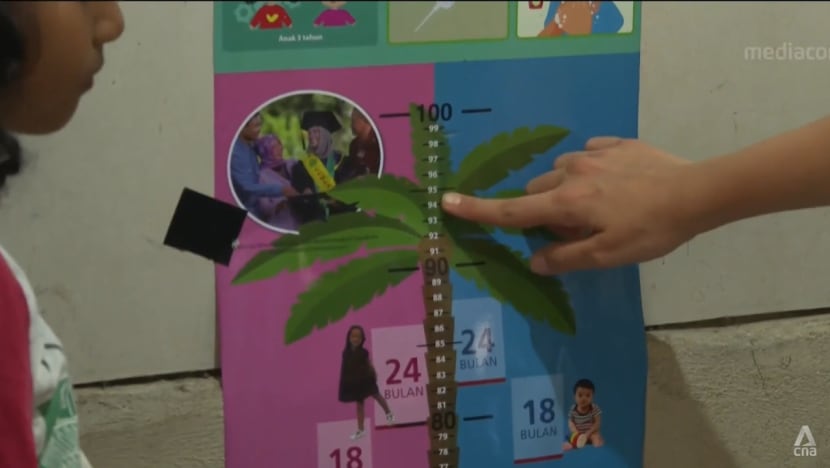

NGO 1000 Days Fund has set up Indonesia’s first Impact Stunting Center of Excellence in Labuan Bajo to train and equip frontline health workers, distribute smart blankets and smart charts to measure a child’s height and assess their nutritional needs.

Parents may not know that 80 per cent of brain development occurs in the first 1,000 days of life, said the NGO’s chief of staff Maritta Rastuti.

“In fact, we also keep repeating this. So this is not an easy path, it’s not an instant fix that after one or two home visits it’s resolved. That is not possible,” she said.