'Accidentally': Johor fishermen say engine failure, strong currents among reasons why they end up in Singapore's waters

Smaller space for fishing activity - partly caused by land reclamation activity in southern Johor - has pushed Malaysian fishermen farther from shore and closer to Singapore's territorial waters.

Johor fisherman Nasir Harun casting his net near the Tuas Second Link bridge off the coast of Johor. (Photo: CNA/Amir Yusof)

GELANG PATAH, Johor: On a cool, breezy evening when there was nothing in the air except for the scent of fish and the call of prayer from the nearby mosque, Mr Nasir Harun stepped onto his boat by the jetty near a fishing village in Johor, and sailed into the open waters.

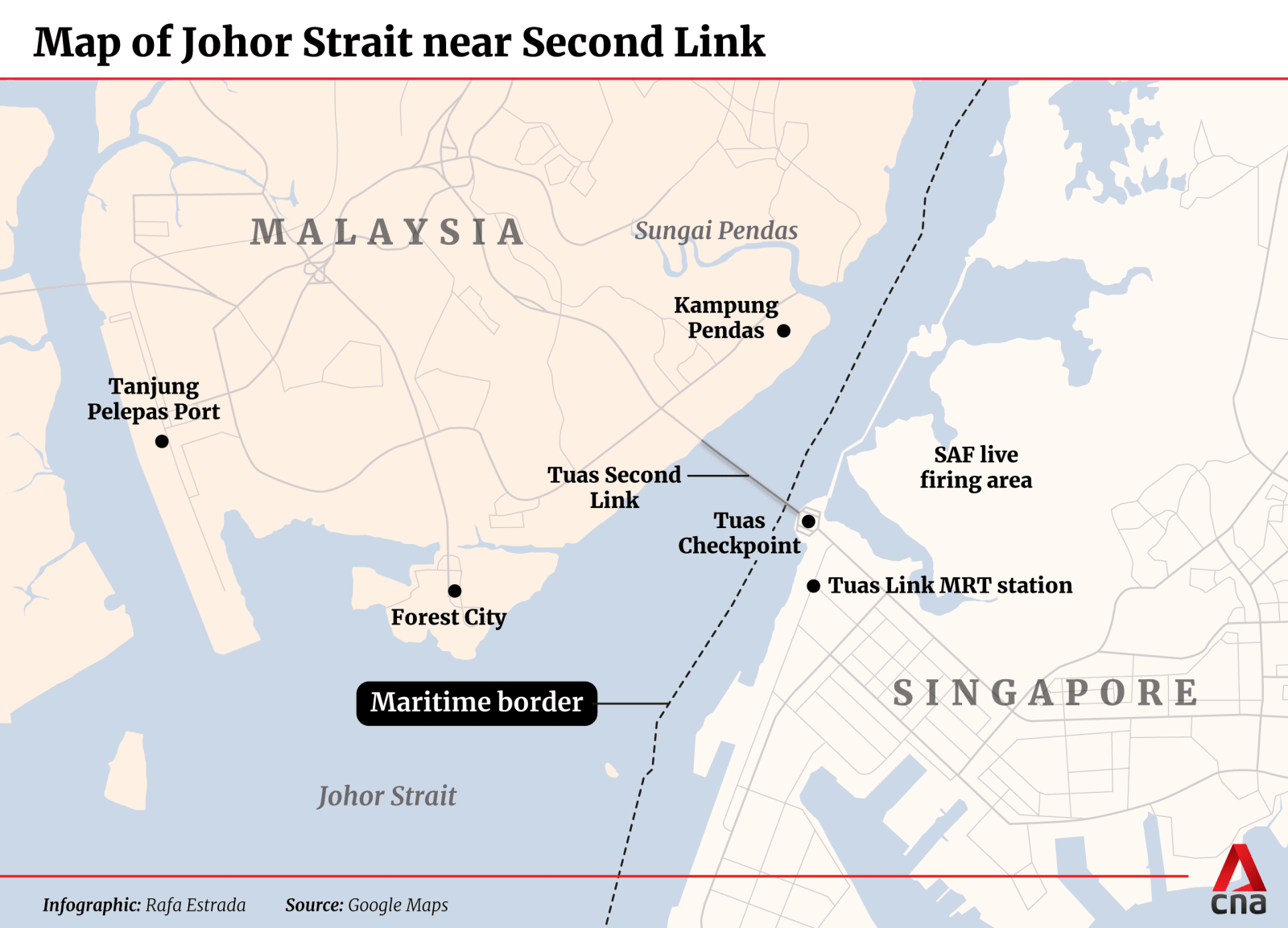

As the 36-year-old cast his fishing net into the waters adjacent to the Tuas Second Link bridge, his eyes darted across the waterway to a Singapore Police Force (SPF) coast guard vessel gliding past.

He also had to constantly keep his focus on a string of coloured water buoys marking the maritime border between both Malaysia and Singapore.

“We would never cross beyond those buoys into Singapore if we can help it. Sometimes due to motor failure or strong current, we may drift over the other side accidentally but we have no intention to do this,” he told CNA.

Like his father, Mr Nasir makes a living combing the Straits of Johor for crabs, prawns and fish.

But in recent years, fishermen like him from the village of Kampung Pendas on the southern tip of Johor say stepped-up patrols by enforcement agencies along the borders with Singapore has made work “disruptive”.

“We really don’t want to cause any trouble with Singapore authorities or anyone else, we just want to earn our living quietly,” said Mr Nasir.

He added that in recent years, the space for fishing in the Johor Strait has seemingly diminished due to land reclamation work off the southern coast of the Malaysian state for residential and industrial projects.

This has forced fishermen further out into the sea, in close quarters with the international boundary line with Singapore, demarcated with colourful buoys.

Faced with depleting catch due to the reclamation activity these fishermen say they also have to navigate the smaller space and ensure that they do not inadvertently cross the international boundary into Singapore waters.

Moreover, the increase in land reclamation activity due to the industrial development of southern Johor has led to fears that the fishing trade in the Strait could no longer exist one day, marine experts say.

'DISRUPTIVE' ENCOUNTERS WITH BORDER PATROL BOATS?

The fishermen of Kampung Pendas once again garnered national attention following an incident last month in which one of them - Faizan Wahid - alleged that a Singapore Police Coast Guard vessel had damaged his fishing net while out at sea.

This has prompted a local politician to call for the remap of international boundaries for the safety of fishermen, accusing the Singapore police boat of “intentionally” hitting the net and entering Malaysia Territorial Waters (MTW).

The Singapore Police Force (SPF) has refuted allegations that the coast guard boat was in MTW and maintained that it was enforcing Singapore law.

SPF said that the fisherman was on board a vessel in Singapore Territorial Waters (STW) and was advised by coast guard officers to leave.

It added that after the engagement, a fishing net became entangled with the propellers of the coast guard boat which was reversing to try to avoid entering Malaysia waters.

A similar incident occurred in October 2022, when SPF said that coast guard officers spotted a group of Malaysian fishing vessels entering and exiting the live firing area of Singapore waters off Lim Chu Kang.

SPF said that the fisherman involved in the incident last month was also involved in the October 2022 incident, adding that he had been then asked to leave a live firing area in STW for his own safety.

According to statements issued by Singapore Ministry of Defence (Mindef), the Singapore Armed Forces do conduct live-firing exercises in the area facing the Johor Straits.

Mindef usually issues advisories for sea vessels sailing through the “Western Johor Strait” to keep within the 75m Navigable Sea Lane and not to stray into the live-firing area as live ammunition and flares are used.

Mr Faizan - the fishermen involved in both incidents - told CNA last Friday that he did not cross into STW on both occasions as what was stated by the SPF.

“I’ve been working on these waters for more than 10 years and I understand the sensitivities of territorial waters,” said the 42-year-old.

“The matter is not yet resolved - I have had to replace the net which was damaged … I’m hoping that authorities for both countries can come up with a permanent solution so that fishermen can work (on the Johor Strait) with sufficient space.”

Mr Nasir said the fishermen's encounters with SPF coast guards, as well as boats from Malaysia’s Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) at the international borders, are “cumbersome” and disrupt their work.

“It's happening more frequently that these boats might stop us at sea and they would check our identification cards. They will scan it and send details back to their headquarters,” said Mr Nasir, who estimates that he gets checked about once every fortnight as compared to once every two to three months previously.

“We would have to wait, maybe between 20-30 minutes for these checks to be done before we can continue to work. At sea, this is not preferable, because time is money,” he added.

CNA has sent queries to both the SPF and the MMEA on why and how identification checks are done on fishermen near the border along the Johor Strait.

Maritime security expert Collin Koh from the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore told CNA that patrol boats regularly monitor the borders to “counter illegal entry, smuggling and other transborder crimes”.

However, he noted that incidents have not escalated to arrests and usually the police would issue a verbal warning to fishermen who would encroach.

There have been no media reports in both Singapore and Malaysia of detention or physical altercations between fishermen and border enforcement officials in the area.

“In fact, I was told, the police coast guard patrols are quite acquainted with the local fishing community in Johor. So there’s probably a level of comfort between them,” added Dr Koh.

Dr Serina Rahman, a visiting fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute who is also a conservation scientist based in Kampung Pendas, told CNA that fishermen in the area would typically be skilled enough to stay within the boundaries unless there is bad weather that impacts visibility badly.

“The coastguard understands that too usually … These incidents and flashpoints are few and far between,” she added.

“And there have been instances when engines break down and some fishermen float across, the coastguard sends them back until someone can tow them to Malaysia waters,” said Dr Serina.

DEPLETING CATCH, DYING TRADE?

The issue of diminished space in the fishing zone is compounded by depleting catch and lower income for fishermen in recent years, who in turn are dwindling in numbers as their offspring seek other jobs.

After more than an hour waiting in his boat, Mr Nasir heaved up his fishing net to empty the squirming contents onto the deck.

He placed six prawns into a box and tossed the rest - small fishes and shellfish - back into the water.

“This is not enough to sell or make any money. I will just keep this for the family to cook a meal,” added the sole breadwinner of his family with a wife and three children.

Mr Nasir said that, five years ago, a three-hour jaunt out to sea could yield between 5-6 kilograms of catch. But these days he would be thankful with 1-2 kilograms.

He said his monthly income used to be RM2,000 (S$583) but these days he frequently brings home around RM1,000 nett for his family, taking into consideration rising costs of fuel and nets.

Mr Nasir added that none of his children are keen to become fishermen, and this is something he has come to terms with.

“I would like it for them to continue the family tradition, (but being a fisherman) is a tough life, especially here in (Kampung) Pendas. I am happy if they do well in school and grow up to become whatever they want to be,” he said.

Mr Nasir suggested that the lower volume of fish catch has been more apparent since land reclamation work has started on the south of Johor - particularly for the Forest City project as well as the Tanjung Pelepas Port.

Mr Jefree Salim, a mussel fisherman who also plies his trade over the Johor Straits, told CNA that his net earnings have dipped by more than half as compared to 2012, more than a decade ago.

“Fishing was much more lucrative and enjoyable then. The Strait was also less crowded and there was more space,” said Mr Jefree.

The conservation scientist Dr Serina stressed that land reclamation has inevitably damaged ecosystems in the area.

“Reclamation brings in a lot of sediment, and also buries seagrass and reduces mangrove. All of this affects fish catch, productivity and marine ecosystem health,” she said, pointing to new projects such as the Benelac development, expansion of the Tanjung Pelepas Port as well as the Forest City residential development project.

She added that climate change has also played a role - with fishermen in Kampung Pendas reporting warmer water temperatures, unusual movement of species as well as increased frequency of severe storms.

ROOM FOR NEGOTIATION OVER MARITIME BORDER?

One Johor politician suggests that a possible solution to save the livelihoods of these fishermen is to negotiate for the maritime border between Malaysia and Singapore in the Johor Strait to be redrawn to allow for more space for the fishermen.

Kota Iskandar state assemblyman Pandak Ahmad told media that he would be tabling a motion in the state assembly sitting next Monday (Sep 11) to remap the maritime border between Malaysia and Singapore in the Johor Strait.

However, RSIS’ Dr Koh told CNA that he is “somewhat sceptical” of the proposal, noting that maritime disputes in Johor such as the Pedra Branca issue has been a “thorn in the relations” between the Johor ruler Sultan Ibrahim Sultan Iskandar and the Malaysia federal government.

“The issue of maritime boundary raised by the Johor politician would have to be addressed by the federal government. Thus the onus will rest on Putrajaya to initiate the discussion with Singapore,” said Dr Koh.

He said that while it is unlikely that Singapore would contemplate moving its maritime border since it involves territorial sovereignty, there may be room for negotiation after meetings were held in 2019 to discuss maritime boundaries delimitation following an earlier spat.

Singapore had protested against Malaysia's unilateral extension of the Johor Bahru Port Limits off Tanjung Piai, which overlapped with Singapore's port limits off Tuas in October 2018.

It said the move led to Malaysia government vessels making repeated incursions into Singapore's waters, with the Republic later extending its own port limits in response, which were still in its territorial waters.

Both later agreed to suspend their overlapping port claims and revert to their former limits, as well as not to authorise and to suspend all commercial activities in the area, and not to anchor any government vessels there.

A committee was also set up to study the legal and operational issues relating to the maritime dispute to provide a basis for negotiations.

Given the ongoing meetings, Dr Koh said: "At first glance this (change in maritime border) doesn’t appear to be a plausible option; it, after all, concerns sovereignty and of course, a matter of principle.

"But I would argue that this prospect isn’t entirely impossible - especially given that the Anwar government is likely regarded as more pragmatic to deal with."

Meanwhile, Dr Serina noted that the reality is that fishing in the area along the Straits of Johor is increasingly not becoming viable as needs for economic redevelopment is likely to take precedence over the livelihoods of the local villagers.

She acknowledged that the silver lining is that these developments will also provide job opportunities to the youths in the area.

“Fishermen are getting endangered,” she said. “Sadly we cannot keep our waters like they were in the 1980s. The whole place is slated for industry and development. It's beyond us.”

As Kampung Pendas fisherman Mr Nasir returned from the sea, and tied his boat to the dock, he carried his box of six prawns and sighed.

“It was a disappointing day out today but perhaps tomorrow will be better,” said Mr Nasir as he looked to the horizon and said a prayer for next day’s catch.

“Changing jobs is not an option, I want to be a fisherman forever so I hope things will improve,” he added.