IN FOCUS: Protecting Sabah’s endangered elephants in the spotlight after handler gored to death

The Malaysian state of Sabah is determined to ramp up elephant conservation efforts. CNA looks at the challenges of protecting these mammals both in captivity and in the wild.

Captive Bornean elephants at Lok Kawi Wildlife Park, near Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. (Photo: CNA/Chris Pereira)

KOTA KINABALU, Sabah: On the morning of Dec 25 last year, Joe Fred Lansou, 49, entered the elephant enclosure at the Lok Kawi Wildlife Park in Sabah, like he has done for the past five years.

But this tragic Christmas Day would also be the last time that the head of Lok Kawi’s elephant unit saw his beloved mammals.

Lansou apparently entered the enclosure alone before treating an injured elephant calf. The next thing workers knew, he was lying on the ground.

Lansou had been gored to death by an adult elephant named Kejora, known as Joe among handlers. The park, near Kota Kinabalu, had just opened for the day, so there were not many visitors around.

Elephant handler Ruhaizam Ruslan remembers how Lansou, a close friend, always reminded him to give proper care to the animals, even in his absence.

“He was always saying things like: ‘Ijam, when I’m not around, make sure you do your best,’” Ruhaizam told CNA, using his nickname among workers at the wildlife park.

“I thought he was joking … but now, he has already passed,” the 37-year-old said with sadness.

The incident made headlines, shining a spotlight on the living conditions of Sabah’s captive Bornean elephants.

There are currently 25 of these elephants across three facilities in the state, taken in from the wild after getting injured or abandoned by their herds.

While conditions in these sanctuaries may not be ideal, elephants in their natural habitats could be at risk of conflict with humans.

ELEPHANT HABITATS AT RISK

Sabah Wildlife Department director Augustine Tuuga told CNA that there are between 1,500 and 2,000 of these endangered elephants in the wild, living in forest ranges in the eastern half of Sabah.

But human activities over the years have reduced the size of elephant habitats, according to experts. And what remains of such habitats often straddle the edges of villages and plantations, leading to encounters between elephants and residents.

Elephants have roamed into these areas, sometimes damaging property and hurting people. Some of them are chased away with flames and loud sounds. In more extreme cases, they are shot at.

“Actually, they have enough area to roam around, but then many elephants walk into plantations and villages and cause damage,” Tuuga said.

“The way we want to keep the elephant population healthy in Sabah is to make sure that there is no hunting. But when they go into plantations, anything can happen. Maybe there are deaths due to poisoning.”

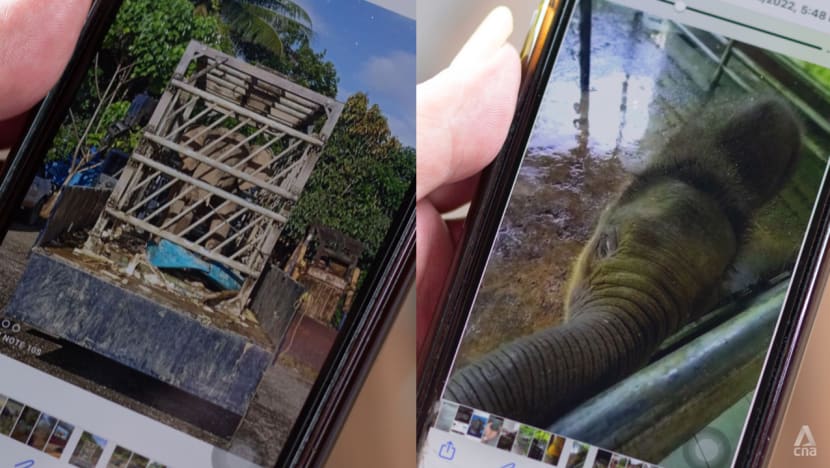

Tuuga showed a picture of a lone elephant found in a village just the day before. The elephant had caused a lot of damage and had to be moved to a forest reserve.

“We really don't understand why (abandonment) is happening. Maybe because of (human) conflict, because of the herd. We just don't understand,” he said.

Authorities will first try moving these elephants back to forest reserves - an operation called translocation that Tuuga said is both costly and dangerous - and reuniting them with their herds.

If this fails - some herds have refused to welcome back old members - the sanctuaries have no choice but to take them in. And after so long in captivity, these elephants cannot survive if they return to the wild.

But Tuuga said these elephant parks have run out of space. For instance, Lok Kawi is home to 14 elephants, double its intended capacity.

There is also a shortage of elephant handlers, as the parks struggle to fund more recruitment. There should be one handler to one elephant, Tuuga said, but Lok Kawi only has six handlers.

“Even one elephant a year is too much for us (to take in),” Tuuga added.

In fact, the elephant that killed Lansou was the sole survivor of a poisoning case that killed 14 other elephants at a Sabah forest reserve in 2013. Joe the elephant was subsequently taken into captivity at Lok Kawi.

“ACCIDENTS CAN HAPPEN”

In a way, Lansou’s death highlights the challenges that Sabah faces in protecting its elephants, Tuuga said, although he cited the free contact between Lok Kawi’s elephants and handlers as a contributing factor.

An internal investigation into the incident has been completed to keep the state government informed on the possible causes, Tuuga said.

“Of course, we cannot fully understand how animals behave, but part of the reason maybe is the situation that we are having here, where you have free contact with the animals,” he said.

“With free contact, anything can happen, accidents can happen. So, our solution is to go for this protected contact.”

A UK-based animal charity that is working with the Lok Kawi Wildlife Park to improve its conditions, including handler safety, said it is “highly complex” to understand how or why elephants hurt their handlers.

“All the various factors that influence such incidents have never been collated,” Wild Welfare field director Dave Morgan told CNA, saying that people are killed by captive elephants each year on a “fairly regular basis”.

Morgan, citing online figures, said there were four deaths in circuses from 2011 to 2015, six deaths from tourism from 2013 to 2021, and nine deaths in zoos from 2011 to 2022.

“However, it is known that all deaths and most serious injuries have only occurred when the traditional style of management is used,” he said.

Tuuga said the state government has approved his department’s funding request to introduce protected contact, which involves always keeping a barrier between elephants and handlers.

Morgan said that renovation designs have been completed, while Lok Kawi’s elephant care staff have been introduced to the concept and routinely use positive reinforcement training in how they manage the elephants.

“The program will be further developed as new facilities come on line enabling the progression of the training program overall,” Morgan said.

FREE VERSUS PROTECTED CONTACT WITH ELEPHANTS

Free contact, where there is no barrier between human and animal, is how elephants are traditionally managed in Southeast Asia, according to animal NGO Wild Welfare.

“However, it is more dangerous for staff and animals and is reliant upon punishment and coercion,” the group said.

Protected contact, on the other hand, involves always keeping a barrier between elephants and handlers. Handlers also use positive reinforcement training to manage the elephants, whose involvement in such training is entirely voluntary.

“Trainers intentionally function outside the elephant social hierarchy and do not attempt to establish a position of social dominance,” said the group's field director Dave Morgan.

But Tuuga of the wildlife department cautioned that implementation will take time as staff need to be trained and facilities need to be built.

“It may not be completed within this year. But hopefully, within next year, we can complete this process because our concern is the welfare of the elephants,” he said.

“They are free roaming here, but there are some that are not free at the moment, so we want to keep all the elephants here.”

The seven free-roaming elephants in the public enclosure include one pregnant female and a three-month-old baby. The baby will only be named once it grows a bit older.

However, another seven elephants - including Joe - that have behaved more aggressively are kept off-exhibit, in smaller cubicles with some of their legs chained to metal railings. The chains are periodically moved to different legs to reduce discomfort.

Tuuga acknowledged that these conditions are not ideal, but were necessary due to a lack of space and to prevent the elephants from breeding as well as hurting staff or each other.

Lansou’s death has also triggered extra safety measures in how all 14 elephants are handled.

For example, Lok Kawi’s handlers now only feed the elephants from outside the enclosure, Ruhaizam the handler said.

As the elephants gathered near the perimeter fence, nodding in anticipation of their feeding routine, the handlers threw in Napier grass, sugar cane and banana tree stalks.

Feeding all the elephants here costs about RM200,000 a month (US$44,788), a Lok Kawi staff member said.

While the elephants were distracted by the food, another group of workers entered on foot - one driving an excavator - to scoop up dead leaves and dung. Previously, feeding and cleaning were done simultaneously inside the enclosure.

In the off-limits enclosure, the handlers must now work together to feed and clean one elephant at a time, with the feeder always observing the elephant’s behaviour. Previously, the team spread out to attend to different elephants at the same time.

Ruhaizam welcomed plans to implement protected contact, saying he would feel safer while caring for the elephants.

“There will be a barrier between us and the elephants at all times, including while training, treating and feeding them,” he said.

LACK OF FUNDS, MANPOWER

Safety considerations aside, the conservation process is also hamstrung by manpower constraints.

Tuuga of the wildlife department said: “The (state) government has a policy of trying to limit the number of government staff, because it will cost a lot of money to pay their salaries and eventually maybe their retirement benefits.”

“At the moment, we are fortunate that many NGOs are complementing our efforts. They engage some of the workers who work with us and pay their salary. But this is not sustainable.”

Tuuga said these non-governmental organisations could one day run out of funds themselves and leave the parks even more short-staffed.

His department is looking at “all the possible ways” to overcome these challenges, including sending some elephants to larger facilities that have yet to be built, or to overseas parks that are open to taking them in.

“We can do as much as possible with the number of staff that we are getting from government employment,” he said, pledging to keep Sabah’s parks running as long as possible, but not if they keep taking in the elephants.

In state capital Kota Kinabalu, Sabah’s tourism, culture and environment minister Christina Liew told CNA that she is not in favour of sending the elephants abroad.

“But I understand what the director is going through because he has to look after so many of these animals in captivity and with so limited staff,” she said, adding that the proposal will be discussed in-depth.

“I hope to discuss with the state government the possibility of improving the facility as well as opening up more conservation (facilities).”

Liew noted that Sabah’s wildlife parks were facing a manpower crunch. “Hopefully within this year, we will be able to make some adjustments to see that such incidents will not happen again,” she said, referring to Lansou’s death.

“It’s a sad incident, but we have to study it from different angles and see what we can do about it.”

CONSERVATION POLICIES

In this context, Liew acknowledged it was only possible to build larger facilities and hire more staff with enough funding, and that this was an issue both the state and federal governments had to tackle.

On Feb 25, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim announced in his budget speech that he will expand a biodiversity conservation fund for state governments from RM70 million to RM150 million.

“At the same time, a total of RM38 million will be set aside to protect wildlife like tigers and elephants as well as their forest habitats,” he said.

Liew said that the Sabah state government has prepared “quite a big” sum of money to conserve both wild and captive animals.

“We already have budgets for each ministry. If you don't have enough, then we will have to inform the state government and present our paper on why we need additional (funds),” she said.

One example, she points out, is the pressing need to redesign and implement protected contact at Lok Kawi.

“I think with this accident, the need for urgent funding has to be presented to the state government and the federal government,” she said.

“I hope to be able to do that in the coming state Cabinet (meeting), with our recommendations on what we should do in the short term as well as the long term.”

In 2020, the state government signed a comprehensive 10-year Bornean Elephant Action Plan, with objectives like improving landscape connectivity and reducing elephant deaths.

A year later, it committed to gazetting more high biodiversity forests as Totally Protected Areas, which will cover 30 per cent of the state by 2025 up from the current 25 per cent.

Sabah’s forestry department aims to achieve this by identifying additional areas where commercial logging will no longer be allowed, further protecting elephant habitats.

The state is also working towards certifying its entire oil palm production under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, an internationally-recognised standard covering issues like deforestation and labour abuses, by 2025.

Sabah currently produces 12 per cent of the world’s palm oil, the third-largest producer behind Indonesia and Peninsular Malaysia.

As part of the certification, plantation companies have to engage environmental assessors to determine if the land they are using is critical for wildlife. Areas determined to be critical cannot be logged.

“While we have the policies, some may overlook those policies. I asked (the wildlife director) how we are going to deal with it,” Liew said.

“He gave some suggestions (but) again, we are dealing with big players. So, let us settle down then we’ll have a more informed discussion on fine-tuning our policies. By right, they’re not supposed to start their work until we get an assessment.”

POISONING CASES, RETALIATION KILLINGS

These measures are important as recent research has shown that for the past 40 years, elephant habitats in Sabah have dwindled by 60 per cent due to land use conversions, said Cheryl Cheah, elephant conservation manager at WWF Malaysia.

Other threats to wild elephants include villagers killing or shooting elephants in retaliation, or inadvertently trapping them in snares when hunting for other animals like wild boars, she told CNA.

Like other parts of Malaysia, Sabah has seen tragic human-elephant encounters. In September last year, a 67-year-old woman was trampled to death by an elephant while riding pillion on a motorcycle near a plantation in Tawau.

“Between 2014 to 2018, there have been a few cases every year that we can say are linked to retaliation killings,” Cheah said.

Cheah said WWF started working with a local NGO two years ago to engage village communities and raise awareness on more humane elephant mitigation measures.

“I think (gunshot-related deaths) have slightly reduced. Since post-COVID, I haven't really heard of such cases,” she said.

“But then there’s the other threat of suspected poisoning cases. That one I think has been slightly increasing, and in particular, for an area in Kinabatangan.”

The Lower Kinabatangan range is the smallest of three regions - behind the Tabin range and Central Sabah range - where Sabah’s wild elephant populations are concentrated.

But Cheah stressed that it was difficult to determine if the poisoning was intentional, noting that elephants could have fed on fruit trees tainted with agricultural chemicals.

Plantation workers, on the other hand, tend to use less aggressive techniques when warding off elephants, Cheah said. Plantation companies have the money to implement measures like electric fences, although this can disrupt connectivity between elephant ranges.

Still, she said some workers do resort to burning rubber tyres and making extremely loud noises to chase elephant herds away, acts that could be linked to abandonment cases. Dead elephants have also been found on plantations over the years.

Elephants have a tendency to seek out plantations because they feed on young palm trees and sometimes puncture water tanks for fresh water, costing plantations millions of ringgit in damage each year.

Elephants also live for many years and can “teach” their babies where to find these specific sources of food and water, Cheah said.

In 2014, WWF Malaysia started working with large plantation companies to mitigate human-elephant conflict, setting up wildlife corridors that connect forest reserves and allow elephants to pass through safely.

These corridors are trimmed of the usual cash crops and replanted with fruit trees that elephants typically feed on, luring them away from other parts of the plantation. Electric fences are realigned to alleviate choke points.

While these measures come at a cost, Cheah said she sells the idea to plantations by promising a good “return on investment”, in the form of less elephant-related damage in the long run.

“CO-EXISTENCE WITH MUTUAL BENEFITS”

In the longer run, measures to promote co-existence between elephants and humans may be more effective.

For instance, the plantation that introduced the wildlife corridor has reaped rewards.

Sabah Softwoods, an oil palm and softwood plantation near Tawau, suffered RM500,000 in elephant-related crop damage in 2004. In 2014, it started developing its wildlife corridor and in 2018 recorded only RM5,000 worth of similar damage.

“All this because of our long-term mitigation plans: Establishing a wildlife corridor and realigning electric fencing,” said Ram Nathan, the plantation’s senior manager of sustainability and conservation tourism.

The corridor, which connects the Ulu Kalumpang Forest Reserve to the larger Mount Louisa Forest Reserve, is 14km long and between 200m to 800m wide. It costs RM7 million over 10 years to build and maintain, Ram said.

The corridor is planted with a mixture of fast-growing trees and slower-growing fruit trees, with artificial pools for elephants to dip in. Besides elephants, animals like hornbills and clouded leopards use it too, Ram said.

While Ram said the plantation still had to call in the authorities to translocate an aggressive elephant in 2021, he insisted that the corridor was making an impact.

“We can see the fruits of it, in terms of the present wildlife and at the same time minimum disturbance into the plantation workers’ area. Now, we can see elephants as an asset, no more like a liability,” he said.

Sabah Softwoods has found another way to benefit from this corridor: Ecotourism.

In 2018, it agreed to work with local NGO and travel company 1StopBorneo Wildlife to start bringing ecotourists into the plantation and catch a glimpse of the elephants safari style. Tourists will also get to plant trees in the wildlife corridor.

“We were afraid that the response might be negative because of the negative stigma attached (to plantations). But no, the response has been great in the sense that they think it is a great conservation initiative story,” 1StopBorneo founder Shavez Cheema told CNA.

“They got to see wild elephants in maybe not the wildest habitats they had imagined. But it is wild and still their natural home, so they accept and agree with the fact that this is a great way to maybe co-exist with mutual benefits.”

Read this story in Bahasa Melayu here.