IN FOCUS: Squid Game, Parasite and BTS – how 'Korean wave' has taken over the world

This undated photo released by Netflix shows South Korean cast members (from left) Park Hae-soo, Lee Jung-jae and Jung Ho-yeon in a scene from Squid Game. (Photo: AP/Youngkyu Park)

SINGAPORE: Dennis Lim did not expect himself to be binge-watching a South Korean television drama.

The 36-year-old has never watched one, describing himself as “more of a movie person”. But urged by friends and curious about the hype surrounding Squid Game, he decided to give it a go.

One episode in, he was hooked. The dystopian drama on desperate men and women in a deadly survival game reminded him of the Hollywood movie franchise Hunger Games.

This time, the games were slightly more familiar.

“The first game ‘red light, green light’ is something that some of us in Singapore have played when we were kids. Childhood games with dire consequences, it’s a great story idea,” said Mr Lim, who ended up watching all nine episodes in one sitting.

Many more were similarly captivated, so much so that the series topped 111 million viewers globally in 27 days, making it Netflix’s biggest original series launch.

It has since inspired countless memes and parodies on the Internet, along with real-world spin-offs such as a Squid Game-themed cafe in Indonesia. Interest in learning Korean has also spiked around the world, while retail orders for the green tracksuits and pink jumpsuits made iconic by the series are reportedly throwing South Korea’s struggling garment industry a lifeline.

For Netflix, Squid Game, which cost just US$21.4 million (S$29 million) to produce, has given it a subscriber boom, pushed up its share price and is set to create an outsized windfall of almost US$900 million.

Media watchers said the global hit marked the latest, if not the biggest pop culture export so far from South Korea, whose TV shows, films and pop music have been making waves beyond the country for at least two decades.

Squid Game’s reach into previously untapped markets is set to amplify the Korean wave, or “hallyu”.

“It’s a big boost,” said Singapore-based independent cultural studies and media researcher Liew Kai Khiun. “Even more, it pushes K-drama to its peak because the following of K-drama has very much been Asia-based.

“The parodies, spin-offs and even merchandise we’ve seen are also quite uncommon. While we’ve had K-drama-based tourism, it has never been as intense as this,” he added.

Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Associate Professor Heo Chul noted that even South Korean movie Parasite’s historic win at the Oscars last year yielded a response that was very much limited to the film community.

“But Squid Game got everyone talking. Like when I’m on the subway and if people know I’m Korean, they start talking about it. And I’m also getting interviews like this,” he said with a laugh.

“Squid Game is a turning point for (Korean wave) to reach out to even more people around the world.”

REASONS FOR SUCCESS

There are several reasons behind Squid Game’s global success.

One is a “strong and complex” narrative derived from the juxtaposition of simple games with violent deaths, while interwoven with hard questions about humanity and capitalism, said Associate Professor Roald Maliangkay who teaches and researches Korean studies at the Australian National University.

The irony of the games can be interpreted in several ways, he added. First, the games may be innocent but to win, one has to resort to betrayals and sometimes unscrupulous means. Second, while deadly, the games are simple enough to offer all an “equalising chance”, regardless of gender or status.

“These deeper ironies around a very rudimentary idea of kids’ games, I think, make it very appealing to the audience,” said Assoc Prof Maliangkay.

Beyond the games, the brutal survival drama is a critique of the modern capitalist world, touching on themes like intense competition in every facet of life, social injustice and a worsening income divide. These may have been inspired by the economic woes in South Korea, but they also resonated with people around the world.

“Global audiences enjoyed the content mainly because they immerse themselves into the show, and they feel similar socio-economic difficulties that are embedded in all capitalist societies,” said Dr Jin Dal Yong, who has authored several books on the Korean wave and is currently a communications professor at the Simon Fraser University in Canada.

The narrative was further strengthened with a diverse set of characters, including an elderly man, a migrant worker and women with strong characters – all of whom are typically absent in K-dramas, said Dr Liew.

“I see this as a very exciting development in K-drama,” he added. “In fact, the most wonderful thing about Squid Game was that the women were the cooler characters.”

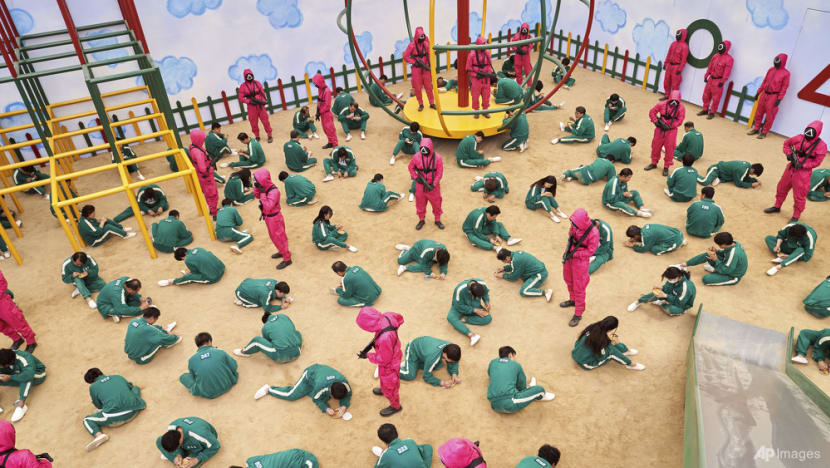

The premise and characters are then brought to life through a line-up of top talent, spectacular sets, striking costumes and a memorable soundtrack, these experts told CNA.

This was made possible with a generous production budget, which at more than US$2 million an episode may be paltry in Hollywood but is “really good money” in South Korea, noted NTU's Assoc Prof Heo who is also a film-maker with three feature films under his name.

“This allowed the director to work with the best talents, spend a lot of effort on art direction and production design. Every decision on the costumes, the set and the choice of colours function as part of the narrative,” he said.

Credit also goes to director Hwang Dong-hyuk, who is a clever storyteller, added Assoc Prof Heo. Like Bong Joon-ho who directed the social satire Parasite, Hwang came from a “unique” background.

“Global hits like Squid Game and Parasite are made by a unique generation of directors who first grew up under a military dictatorship from when they were born in the 1960s and 1970s until the 1980s.

"And when they reached late 20s and early 30s, the Asian financial crisis hit so they also experienced how economic problems could change people's daily lives. These life experiences helped them to develop greater sensitivity towards political and economic issues,” he explained.

Still, Squid Game has drawn some criticism, such as the quality of its English subtitles. Some say the translation did not do justice to the brilliantly written script and dialogue.

Assoc Prof Heo said this is a case of cultural-specific nuances found in native languages that are hard to translate.

For instance, some male characters in the series use Korean slang that refers to women as subordinates. This was left out in the English subtitles, along with a common honorific – “hyung” – used by Korean men to address an older brother or an older male friend.

“There is a seniority connotation in ‘hyung’ but this delicate nuance cannot be translated into English so the subtitles reflect the character’s name,” he said. “Unless you really understand the Korean culture, society and language, it’s really hard to translate all these.”

THE RISE OF HALLYU

While Korean entertainment may be at a “major peak” right now, its global influence “did not come suddenly and out of nowhere”, said Dr Jin. Instead, it is built upon a Korean wave that has grown since the 90s.

Two decades ago, with the aim of diversifying its economy, South Korea set its sights on developing its cultural industries. In 1994, a government white paper famously noted that a single blockbuster movie, Jurassic Park, earned the equivalent of selling 1.5 million Hyundai cars. The government also abolished strict censorship rules, established a new commercial broadcasting system and developed legislation like the Korean Film Promotion Act of 1995.

“They realised that a single good cultural product could be very lucrative and would probably sustain the Korean economy in ways that maybe car sales, with all the competition, might not. And that investment was necessary,” said Assoc Prof Maliangkay.

This grew in importance following the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Following the inauguration of President Kim Dae-jung in 1998, the country established a “Basic Law for the Cultural Industry Promotion” the following year and allocated US$148.5 million to this project.

Since then, the South Korean government has furnished the cultural sector with tax breaks, grants and legal support.

But industry experts said it would be “completely wrong” to credit the government for creating the Korean wave.

“The government has certainly utilised its legal and financial mechanisms to develop and support the cultural industries. However, the role of the government has not been substantial, other than building necessary infrastructure for the growth of hallyu,” said Dr Jin.

Creators in the private sector played a “pivotal role” by developing popular content, he said. For example, MBC and KBS, the country’s two biggest network broadcasters, had by then set up their own agencies to deal with foreign exports of their dramas. Several large conglomerates, including Samsung, Hyundai and Lotte, also started investing in films.

In the realm of music, singer Lee Soo-man established entertainment house SM Studio in 1989 before renaming it as SM Entertainment in early 1995. Lee was an instrumental figure in changing the Korean music landscape, turning “a very primitive way of music creation into an industry”, said Assoc Prof Heo. This later paved the way for other music agencies, such as JYP and YG, which collectively contributed to the boom of K-pop.

“Overall, the growth of the Korean wave is arguably the result of sometimes cooperative and at other times conflicting relationships between the public and the private sectors,” said Dr Jin.

Later on, the massive use of social media, like YouTube, became a key force that propelled the Korean wave from the late 2000s. Dr Jin noted that this broadened the fanbase of “Hallyu” from being primarily women from East Asia in their 30s and 40s to more diverse age groups and markets, such as teens in Western countries.

In recent years, over-the-top platforms like Netflix have also been “a gamechanger”, according to Singapore-based researcher Dr Liew. They allowed South Korean content to reach more global audiences directly and pushed the boundaries of K-dramas beyond romance into grittier themes like Squid Game.

Notable K-drama hits over the years include Winter Sonata and Dae Jang Geum in the early 2000s, Coffee Prince and Boys over Flowers in the late 2000s, as well as My Love from the Star, Descendants of the Sun, Goblin and Kingdom over the next decade.

Idol groups like Super Junior, Girls’ Generation and Big Bang began breaking out of Asia by the early 2010s but it was rapper Psy who made history in December 2012 with mega-hit Gangnam Style. The song became the first music video to reach 1 billion views on YouTube.

Since then, BTS has emerged as arguably the country’s most successful K-pop group of all time, breaking chart records and garnering millions of fans worldwide.

Last year, the seven-member global sensation became the first K-pop group to ever receive a Grammy Award nomination. The same year, Parasite, a black comedy centred on inequality and class conflict, rewrote Korean film history by winning four Oscars, including the prestigious Best Picture award.

The biggest successes out of South Korea have been those that touch on socio-cultural issues which resonate with global audiences, said Dr Jin.

“Even for BTS, they often write and sing about their struggles, especially in the early stage of their debut. But while they are in a dire situation, they work hard to overcome the challenges,” he added, noting that the message of hope has been one of the boy band’s key appeals to youths globally.

ECONOMIC BOOST, SOFT POWER

The global success of the Korean wave has given South Korea a boost in many ways.

First, its economy.

Cultural content exports, which music, film and TV programmes fall under, rose 6.3 per cent to US$10.8 billion last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the overall size of the industry remains small – accounting for just 0.7 per cent of South Korea’s gross domestic product – it has had “a positive impact” on employment in the arts and recreation-related sectors, said Mr Lloyd Chan, senior economist at Oxford Economics.

Another government report extrapolates the impact of hallyu on these cultural content exports.

A report dated October 2020 by the Korean Foundation for International Cultural Exchange (KOFICE) showed that the value of such exports due to the Korean wave more than doubled to US$6.4 billion in 2019 from three years ago.

This accounted for 62 per cent of the total value of cultural content exports in 2019, it added, noting a rise in the direct economic impact of hallyu over the years.

Elsewhere in the economy, the Korean wave has also caused a ripple in industries such as tourism.

South Korea’s inbound tourist arrivals have been on an uptrend before the pandemic occurred, except for a drop in 2017 amid a diplomatic row with China, and hit an all-time high of 17.5 million in 2019.

This in turn boosted other industries such as cosmetics, skincare, fashion and food, with holidaymakers eager to bring home a slice or a piece of South Korea.

The KOFICE report similarly showed an increase in the export revenue of consumer goods due to hallyu – from US$4.4 billion in 2016 to US$5.9 billion in 2019. Food, cosmetics and tourism benefited most from the positive impact.

Mr Chan expects Squid Game to help amplify the growing appeal of Korean culture to the world. “This will have a positive spillover impact on Korea’s tourism sector at a time when global travel is gradually resuming,” he added.

However, the economist reckoned that a full resumption in international travel will likely take some time so “any gains in the tourism sector due to Squid Game will likely remain limited due to the ongoing pandemic”.

Agreeing, UOB economist Ho Woei Chen said: “Even with the tourism pick-up from the gradual reopening of vaccinated travel lanes and the popularity of Squid Game, which has temporarily provided a boost, it will be some way before we can see an impactful uplift to employment rates.”

Second, its soft power.

“With several well-made Korean popular culture (exports), Korea has been able to build its reputation as a cool and advanced cultural place, attracting more foreign tourists and investments,” communications professor Dr Jin said.

The country’s politicians have also been keen to tap on this for political or diplomacy purposes, he added, citing how South Korean President Moon Jae-in appointed BTS as “special presidential envoys for future generations and culture” and awarded them with diplomatic passports.

The boy band also appeared alongside President Moon at the United Nations last month to promote sustainable development.

Said Dr Jin: “BTS is a symbol of the Korean pop culture and the government, be it liberal or conservative, is keen to seize on the global popularity of the Korean wave to build national image and identity.”

WHAT’S NEXT

With Squid Game translating into a remarkable pay-off for Netflix’s investments in South Korea, other foreign big names are jumping on the bandwagon.

Apple TV+, for instance, will be launching its service in the Asian country next week with Korean-language originals such as sci-fi thriller Dr Brain starring Parasite star Lee Sun-kyun.

Disney+, the streaming service of Walt Disney, will join the competition next month. South Korean media have reported that the company intends to invest heavily in creating seven original Korean content releases, including a spin-off from the long-running television variety show Running Man.

Hot on the heels of Squid Game, Netflix has recently released action drama My Name featuring up-and-coming South Korean actress Han So-hee. The streaming giant said earlier this year that it will increase its investments on South Korean projects to US$500 million in 2021, after having spent US$700 million since its market debut in 2015.

Assoc Prof Heo said the entry of Western media giants into South Korea and the ensuing competition will translate into more opportunities and bigger production budgets for local creators.

But he is worried that younger directors may be left out of these opportunities, if foreign studios opt to partner established directors instead.

He is also concerned that if more directors choose to work with streaming platforms such as Netflix, this could eventually hurt the cinema industry which is already struggling with a lack of film releases and pandemic-restrictions on capacity.

A report this week by Yonhap News also highlighted questions over the monopoly of intellectual property rights by streaming platforms, which often demand the “entire IP (rights) of the shows they invest in” as part of taking on a larger share of the investment.

For instance, the Oct 27 report cited insiders as saying that Netflix “shoulders the entire financial responsibility for a project, allowing local producers a 10 to 30 per cent profit margin, in return for global distributing rights of the underlying show and its copyrightable works”.

It added that Hwang, director of Squid Game, and his production crew “will have no additional income and incentives” even with the series’ global success.

Meanwhile, there remains competition from other regional countries, in particular China and Japan.

“These East Asian countries have continued to develop their own cultural content, while partially preventing Korean culture from airing on TV and at theatres,” Dr Jin said.

He added that to overcome these challenges, the South Korean cultural industry should develop their own over-the-top platforms or at least work with global players like Netflix on “fair terms”.

Dr Jin also observed that South Korea is “losing talent” to China, which has been recruiting the country’s directors, producers and even actors and actresses with lucrative salaries.

That said, there are bright spots on the horizon, with new industries such as webtoons or digital comics set to be the next big craze.

This has been a burgeoning space, experts said, since the advent of smartphones and the Internet. Fans are also drawn to this new form of content given a wide diversity of genres.

Webtoons have since been adapted into several dramas and movies such as Itaewon Class and Space Sweepers, both produced by Netflix.

“I want to emphasise the significance of webtoons as sources for big-screen films and television dramas,” said Dr Jin.

“This is just starting and therefore, we may witness the soaring popularity of Korean webtoons and webtoon-based cultural products. They may be the cultural content for the next generation of Korean wave.”