A battle between three forces: Thailand’s election explained

For the first time in nearly five years, Thailand will leave the military rule for democracy. Here is what you need to know about the Thai election on Mar 24 and the political game that would determine its future.

Thailand is set to hold a general election on Mar 24, 2019 - the first since a military coup brought down a democratically elected government under former prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra in 2014. (Photo: AFP)

BANGKOK: The upcoming election in Thailand is set to be one of the most complicated votes in the country’s history, with the final outcome of who will form the next government dependent on a series of factors.

On a very simple level, though, the vote on Mar 24 will be the first general election under the new Constitution of 2017. It should mark a transition towards re-establishing a democratically elected government after nearly five years of rule by a military regime which took power through a coup in 2014.

However, while some people believe the upcoming election will restore democracy, others believe there is scope for a subtler shift that could see the powerful military maintain its grip on Thai politics.

“It’s not a regular vote under democratic rules but a means for regime change, where the military rule is reborn to continue its power,” said political scientist Dr Pitch Pongsawat from Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University.

This election is an attempt to legitimise the military regime which plans to stay.

According to Dr Pongsawat, the upcoming vote gives the military leadership the scope to retain a significant degree of control over the political landscape under the banner of Palang Pracharat – a newly-formed party that is supportive of the junta. Its prime ministerial candidate, Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, is Thailand’s current premier and leader of the coup that toppled Yingluck Shinawatra’s democratically elected government in 2014.

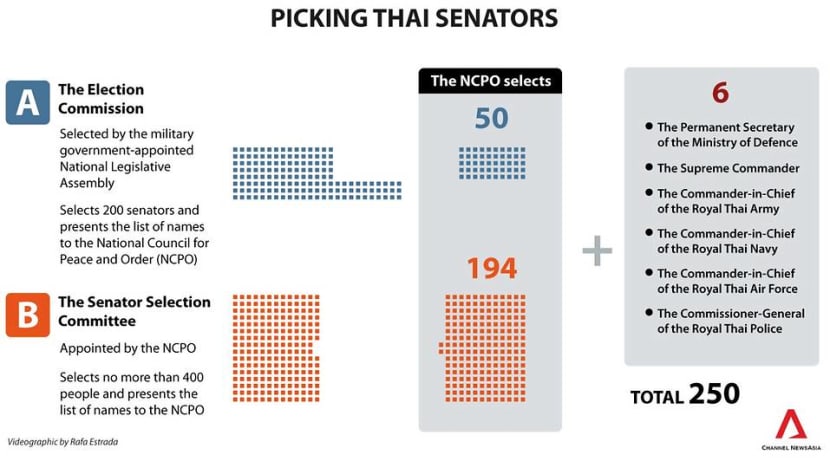

But even if Palang Pracharat makes little headway at the ballot box, the military will be assured of a high level of influence over whatever government emerges after the election: Its generals, who are currently in control through the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), will select and appoint 250 senators whose votes could determine the future prime minister.

Based on reports by Thai media, the senator candidates are mostly seen as having close ties with Gen Prayut and his associates. Most of them have been handpicked by the NCPO deputy chief Gen Prawit Wongsuwan, who heads the selection committee of senators.

THE POWERFUL SENATE

The new constitution gives power to the Senate - the upper house in parliament - to jointly select the prime minister in conjunction with the House of Representatives - the lower house - during the initial five years of the first government to be formed after the election.

According to the constitution, a prospective prime minister must be approved by more than half of the combined 750-member assembly. As a result, a political party needs to garner at least 376 votes in a joint sitting – either from both Houses or only from the Lower House's 500 members – in order for its candidate to win the premiership and form the government.

The Senate’s role in the prime ministerial selection means Thailand’s future government does not need to win the popular vote if it can secure support from at least 376 parliamentarians.

Compared to other parties, the Palang Pracharat will have a clear and built-in advantage in the Mar 24 contest, thanks to the 250 senators that will be selected by the NCPO and Gen Prayut himself. It will mean that Palang Pracharat could be in a position to form the government even if it wins as few as 126 of the 500 parliamentary seats up for grabs.

“We have to take full advantage of these things,” said one of the party’s core members Somsak Thepsuthin last November.

In this election, this constitution was designed for us.

A BATTLE OF 3 FORCES

Despite the potentially decisive role of the Senate in forming a new government, the upcoming election will still return a significant amount of power to members of the public casting their vote - after years of living under a non-elected government.

According to the Interior Ministry, an estimated 51.4 million people will be eligible to vote on Mar 24. They will be voting for 350 members of parliament which will be drawn from three broad groups: The pro-military faction, a group of parties opposed to the military and those parties which have yet to indicate which side they will support, if any.

- The pro-military force supports Gen Prayut’s return to power. It is made up of newly-formed parties such as the Palang Pracharat, the People’s Reform and the Ruampalang Prachachart Thai.

- The anti-military force opposes the military government. Its key member is one of Thailand’s biggest parties - Pheu Thai, which was the party of former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his family. Others include its affiliates – the Pheu Tham, the Pheu Chart and the recently dissolved Thai Raksa Chart – and pro-liberal democracy parties such as the Future Forward, the Commoners and the Thai Liberal.

- The swing force consists of old parties that are yet to decide which camp they would join. Among its members are Thailand's oldest party the Democrat, the Bhumjaithai and the Chartthaipattana.

It is the last group which may wield a high level of influence in the election's final outcome.

“This is a big group of old politicians who are ready to join anyone. The Democrat believes it could win more votes than the Palang Pracharat and wants to establish itself as an ‘anti-Thaksin’ party with distance from the military – an alternative,” Dr Pongsawat told Channel NewsAsia.

“If the ‘Thaksin camp’ is popular in this election, the Palang Pracharat won’t be. But this could benefit the Democrat, given its stable base in Bangkok and southern Thailand. The party could team up with the junta’s camp and lead the government itself,” he added.

The Democrat is one of two parties fielding candidates in all 350 constituencies. The other party is the Future Forward, which will be making its Thai election debut. The newcomer had previously made it clear it will never join the pro-military camp, but until recently, the Democrat – largely seen as a ‘swing party’ – had not.

But then on Sunday (Mar 10), Democrat leader Abhisit Vejjajiva announced he will not support Gen Prayut in the upcoming election.

"Let me be clear," he said in video clip published on his social media platforms.

I will certainly not support Gen Prayut to be prime minister again because power inheritance creates conflicts and opposes to the Democrat's ideology where the people rule. Over the past five years, the economy has been depressed and the country has been damaged enough.

The Democrat positions itself as "the third option", according to its secretary-general Juti Krairiksh.

"We’ve prepared to claim victory. We’ve never considered ourselves a secondary party. So, if my party wins the majority vote, I’d rather ask ‘who wants to join me?’," he said on Feb 23 in a political debate.

DIFFERENT RULES, DIFFERENT OUTCOME

The Democrat is among 81 parties contesting the upcoming election, where 10,792 candidates will fight to represent 350 constituencies.

The other 150 members of the House of Representatives will be elected from the so-called national party lists under a system of proportional representation.

This will see each party that contests the party-list election have a number of MPs in the House of Representatives according to the share of the popular vote it secures in the contest for the 350 directly elected members. Parties can still secure seats in parliament under this system irrespective of whether their candidates win any of the 350 contests.

The proportional representation approach is a change from previous elections, when people would cast two votes: One for directly elected MPs, and one for party-list candidates.

According to the Constitutional Drafting Committee, the new voting system should better reflect the popularity of each political party. One member of the committee, Chatchai Na Chiangmai, has said that the fact that every single vote counts will force political parties to pay more attention to their choice of candidates.

For many political observers though, the revised system has flaws and could confuse voters. A survey by the National Institute of Development Administration in November showed 77.8 per cent of 1,261 respondents were unaware of how many ballots they will have to cast.

“It’s confusing,” said Yingcheep Atchanont from legal monitoring group iLaw. “With a single ballot, voters can’t make separate choices between an MP they prefer and a party they like. So, many votes will not reflect what the people really want.”

The new system is also viewed by some politicians as the military government’s ploy to weaken big political groups, particularly the Pehu Thai Party.

In the previous election of 2011, Yingluck Shinawatra led that party to win 265 seats in the Lower House. But with the new electoral method, it would only have 225 seats.

THE ‘OUTSIDER PRIME MINISTER’

Once the seats in the House of Representatives are decided, the race for the premiership begins. This time, 68 contenders from 44 parties are running for prime minister.

According to the 2017 charter, the premier does not have to be an MP but he or she must be one of the prime ministerial candidates listed by a political party. That party must also have at least 25 elected MPs – or no less than 5 per cent of the Lower House’s 500 members – before it can nominate a candidate to be appointed prime minister.

The nomination must then be endorsed by at least 50 elected MPs – or no less than one-tenth of the Lower House’ total members – before a vote to select the prime minister can take place in a joint sitting during the first five years.

However, if none of the listed candidates can be appointed for any reason, at least half of the members of both Houses – 375 – can request the National Assembly to start a process that could allow an ‘outsider prime minister’ who need not be a listed candidate previously known to voters.

“This is unacceptable,” said Atchanont from iLaw. For him, the prime minister should be a member of a political party and join its election campaign – a crucial process he believes would create a rapport between candidates and voters.

Meeting voters allows them to learn what the people want and to promise solutions. Without this process, the prime minister may be constitutional but never dignified.

Meanwhile, although concerns have been raised about some of the mechanics through which the election will be fought, what is certain is that this will be an opportunity for people to make their voices heard at the ballot box for the first time in almost five years.

Less certain is the outcome, and whether the military government will relax its grip on the country.