In war-torn northern Myanmar, communities unite to save youths from drugs

In a battle against drug addiction, the northern Myanmar state of Kachin has opted for community-led programmes, where its residents join hands with local churches to save young people from what they describe as a “genocide”.

Kachin drug addicts take part in an activity at the Rebirth Rehabilitation Centre in Myitkyina, Myanmar. (Photo: Pichayada Promchertchoo).

MYITKYINA, Myanmar: In Southeast Asia, Myanmar is second to none when it comes to drug production.

Straddled between China and Thailand, the former pariah state is the world’s second largest producer of opium after Afghanistan. This year alone, it has injected an estimated 647 tonnes of opium into the global drug market, according to the latest report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) – the 2015 Southeast Asian Opium Survey.

Opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar, the survey showed, has remained “stable” at high levels since 2013, spanning more than 55,000 hectares of land.

However, it is not the sole commodity. Besides the reddish-brown drug, which is derived from opium poppies’ milky juice, the nation is also well-known for manufacturing its highly addictive derivative, heroin, mainly prevalent in the war-torn states of Kachin and Shan.

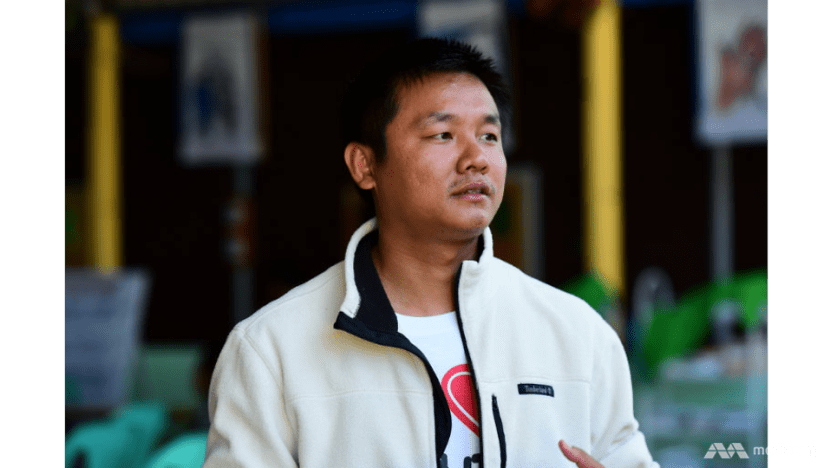

“Previously in Kachin State, we could get the drug everywhere at a very cheap price,” said Nlam Hkun Aung or Peter, the director of the Rebirth Rehabilitation Centre in the Kachin capital of Myitkyina, where a dose of heroin cost around 600 kyats or 50 US cents.

“At Myitkyina University, many students have become addicted to heroin because you could get it within the university’s compound. Many dealers were operating there; some were students, others were outsiders,” the 31-year-old said, recalling a grim picture of the campus, where bloody syringes and needles lay scattered.

In fact, there were so many of them that special bins were installed to prevent people from injuries caused by stepping on the discarded needles.

SILENT ‘GENOCIDE’

Heroin addiction has long been a crisis in Kachin State. While UNODC puts higher income and poverty as the main incentives for the thriving poppy cultivation, many Kachins blame it on the military.

“In Kachin State, if you ask what Kachin people have on their mind, it’s the KIA and the KIO,” Peter explained, referring to two main insurgent groups fighting for freedom from the centralised government.

“They can’t eliminate all the Kachin people with bullets. So, one key tool is drugs,” he claimed.

For decades, the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) and its armed wing the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) have been fighting to create a federal union within the multi-ethnic nation. Since June 9, 2011, violent clashes between the KIA and the Myanmar Army have displaced about 100,000 civilians, many living in some 100 shelters across the state.

“We feel that the drug issue is some kind of genocide to our ethnic group,” Peter said. “The spread of drug is their big victory. There is no need to use bullets.”

However, in this year’s survey, UNODC identified efforts, including prohibition, by local authorities as one of the key factors in reduced poppy growing.

In its efforts to eradicate drugs, Finland pledged to help Myanmar farmers turn their opium fields into coffee plantations with a donation worth US$3.3 million. The sum will be allocated over the period of three years by UNODC.

"UNODC has been helping to set up a cooperative of 800 farmers so far,” said Troels Vester, country manager for UNODC in Myanmar. “We hope that we can add another 1,000 farmers into this cooperative, and we need to connect them to coffee buyers in the world."

The programme, however, is not without challenges, Vester added:

“One of the main challenges is that opium production is very high where the government is not in control but ethnic armed groups. The ethnic armed groups are also suffering from this because of drug abuse within their armed forces and within their own area.”

COLD TURKEY

From the perspective of the likes of Peter, who also serves as the coordinator of the People with Chemical Dependency Programme (PCD) in Kachin State, the Myanmar government has not done enough to eradicate narcotics.

“The corruption is so obvious. I’m a civilian and I know who sells drugs and who is using it. How come the government doesn’t know that? The government must know more than we do,” he said.

Located in Myitkyina, the Rebirth Rehabilitation Centre forms part of a sprawling network of anti-narcotics movement in the restive state, where the local community works with church leaders to save their youths.

Founded in August this year, the facility was designed to help drug addicts start a new life through various kinds of support, from medical therapy to social reintegration programmes and aftercare.

Most of its 30 clients, aged between 18 and 22, are heroin users who joined voluntarily.

According to Peter, who has travelled to the Philippines and Hong Kong to learn about running a rehab centre, clients are required to go cold turkey in the first two weeks of admission before proceeding to complete the four-month rehabilitating process.

Unlike many international centres, however, most of the methods used in the facility are traditional. “For example, when they crave for drugs, we encourage them to take a bath. They’ll feel better afterwards. That’s a traditional way,” Peter explained.

“We’re also more focused on using Bible teachings to facilitate recovery. We teach our clients how to meditate and reflect upon themselves.”