Why Indonesia is jolting markets by curbing commodity exports

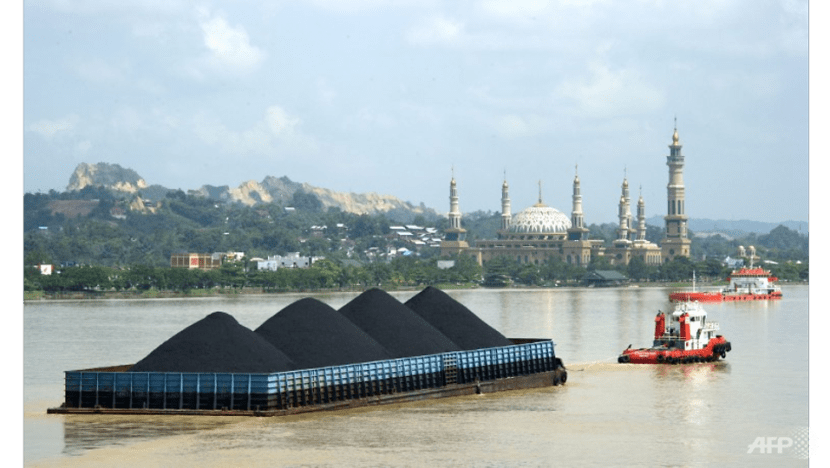

Indonesia is the top exporter of coal for power stations and the biggest palm oil producer in the world. It also holds a quarter of all nickel reserves. So policy shifts in the Southeast Asian archipelago - such as new restrictions on coal shipments or a proposed nickel export tax - often reverberate across global commodities markets, roiling trading and pushing up prices for other countries that need the supplies.

President Joko Widodo is nevertheless forging ahead with what’s known as resource nationalism, policies designed to get more benefit from the country’s natural riches for its 273 million people by restricting exports and encouraging more value-added processing at home. The going has been slow but there are signs the strategy is having an effect.

What’s in the spotlight now?

Coal and nickel.

- A surge in global coal prices in 2021 prompted miners to shun the domestic market, despite rules that specify a quarter of output should be sold to local buyers. Shipments by sea of so-called thermal coal, used for power plants and other furnaces, surged to more than US$246 a metric tonne in October, according to China Coal Resource. That compares to a price cap of US$70 a tonne for sales by Indonesian producers to domestic power plants, which still rely mainly on coal. State-owned power company Perusahaan Listrik Negara was grappling with a dwindling stockpile, risking blackouts that could have affected millions of residents. So the government last year temporarily banned 34 exporters from shipping coal abroad, followed by a more drastic halt on all exports in January 2022. The Philippines and Japan were among the major importers to protest to Indonesia.

- Meanwhile, to encourage investment in Indonesia, the government said in January it could impose a new export tax on nickel pig iron (a lower grade of pure nickel) and ferronickel (a semi-refined product) as soon as this year. The president, known as Jokowi, said in November that Indonesia could generate about US$35 billion of added value by refining more nickel domestically rather than shipping raw material overseas for such things as stainless steel and electric vehicle batteries.

What’s the background?

Indonesia has a long history of being plundered, since the Dutch began collecting nutmeg and cloves from what they called the East Indies 400 years ago. Even in modern times, changing the dynamic hasn’t been easy. Indonesia banned metal ore exports in 2014 to encourage local smelter construction, arguing that too much wealth was shifting to refineries overseas and to foreigners. It later relaxed some of those rules partly in an effort to help producers cover the cost of constructing new refineries.

A decision in 2019 to bring forward the date of curbs on sales of nickel ore overseas by two years - to early 2020 - sent global prices of the metal surging again, as consumers including China rushed to secure supplies. But after the initial jump, the market adapted quickly - helped by those preparations and weaker demand due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s the ambition?

Jokowi, whose second and final term ends in 2024, has repeatedly said he wants to eventually stop exports of all raw commodities in favor of producing refined goods that would create more jobs and improve the nation’s trade position. Indonesia wants to be a global player in EV batteries and a regional player in the production of electric cars, with a target to be a supplier of key products like nickel sulfate, battery precursors and cathode materials by 2025.

The government has said it will halt bauxite and copper ore shipments, with the ultimate goal of producing all EV components onshore. For coal, the target is to accelerate development of a coal-to-chemicals industry and to begin coal gasification projects that could offer an alternative to costly liquefied petroleum gas imports.

Is it working?

Somewhat. Exports of higher-value nickel pig iron rose after the curbs on lower-cost nickel ore shipments, indicating some success. And investments in Indonesia are accelerating. Chinese nickel producers like Tsingshan Holding Group are adding projects, including in the key producing regions of Sulawesi and Maluku. From 19 mineral smelters now, a total of 53 are expected to be operating in 2023, including new plants for Vale SA’s local unit and Antam, the Indonesian state miner.

The South Korea conglomerates Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution held a virtual groundbreaking in October on a US$1.1 billion EV battery plant, with commercial production expected to start in 2024, according to the companies. Chinese giant Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. has expressed interest, while Foxconn Technology Group discussed investments with Indonesia’s government in October. In the coal sector, U.S.-based Air Products Inc. is partnering with state-owned PT Bukit Asam and PT Pertamina on a gasification project.