‘I will die too’: What’s at stake in India’s reliance on coal power

Coal helps poor families stave off hunger. But it could kill in the longer run and worsen the climate crisis. The programme Insight examines the costs that India, home to the world’s largest coal producer, must weigh.

Millions of Indians are dependent on coal and related industries, like these men transporting the fossil fuel on their bicycles.

JHARKHAND, India: In Dhanbad city, otherwise known as India’s coal capital, 13-year-old Gauri Kumari’s family depends on the black fuel she collects each day to survive.

It is a hard life for the teenager, who lives in one of the squatter colonies surrounding the coal mines.

At 8 p.m. daily, she heads out to the mines and returns between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m. Barely four hours later, she wakes up to gather coal again before attending school. After returning from school at about 1 p.m., she makes a third round before her tuition classes.

The coal is later sold to traders. And if she cannot collect any owing to police presence or guards at the mines or owing to rain, the family must depend on the few rupees her mother earns from making samosas.

“My mother cooks rice but without any vegetables. Sometimes we just eat plain rice and sleep,” said Gauri, whose father is incapacitated by a fall.

Trips to the mines are risky. “If we’re caught by police, they tell us not to repeat the act and scold us,” she said.

“We tell them we won’t be able to eat if we don’t do that. They say they don’t care whether we eat or not.”

In the Jharia subdivision of Dhanbad, mother-of-five Ruby lost her husband last year.

Ranjeet, who died aged 40 from tuberculosis, had also depended on coal for a living — either by filling coal trucks or stealing coal to sell to traders for 50 to 100 rupees (S$0.90 to S$1.80) a day.

It is now up to 35-year-old Ruby, who goes by one name, to collect and sell coal.

“I go at 4 am to collect coal. Security guards make us run. I carry coal baskets on my head and sell the coal in the lanes,” she told the CNA programme Insight.

“All my relatives are dead … My father, brother and mother — everyone,” she added. “I suffer from chills and am weak. I will die too.”

For Ruby and Gauri, coal is both a short-term lifeline and a potential killer. They are caught between a rock and a hard place, and their situation highlights the tension and challenges that India faces in phasing down coal.

COAL ADDICTION?

Coal is the single biggest source of man-made climate change, contributing more than 40 per cent of global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.

Although India consumes less coal than China, it derives a bigger proportion of its energy from the dirtiest fossil fuel (about 70 per cent, compared to China’s 57 per cent).

The lesser ambition of phasing down — instead of phasing out — coal stirred controversy at the recent United Nations climate conference, or COP26, in Glasgow.

India and China had pushed for a watered-down pledge, dealing a blow to the Glasgow Climate Pact and efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Related articles:

Various experts have since argued, however, that India was not the climate villain. Although the country of 1.3 billion people is the world’s third-largest emitter after China and the United States, its per capita emissions are lower than many countries.

Rich nations, which account for the bulk of historical emissions, have also failed to deliver climate finance to poorer countries, experts noted. This includes the US$100 billion (S$134 billion) per year they committed, in 2009, to less developed nations by 2020.

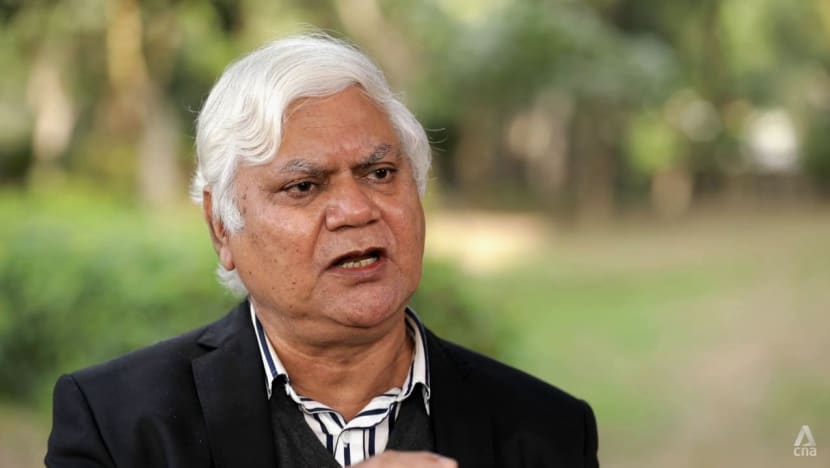

For its part, India must sustain economic growth to pull more people out of poverty, said Narendra Taneja, an energy expert and spokesperson for India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. To do so, it needs energy.

Given the country’s rich coal reserves, relying on the fuel also offers energy security, he said.

“Look at, for instance, oil — 86 per cent of the total requirement is imported,” he noted. “Fifty-six per cent of our natural gas is imported … Quite a bit of uranium is imported. Even solar power — 90 per cent of equipment is imported, mostly from China.

“The only source of fuel that gives us absolute confidence and 100 per cent energy security is coal, because coal is in our own ground.”

Scientists have said global emissions must peak as soon as possible to avoid the worst effects of climate change, and he agreed that India must “fast-track” the transition to renewables “for the health of our people, our children, our grandchildren”.

He believes India can reach its net-zero target sooner than 2070 — the timeline pledged by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at COP26 — although Taneja argued that India “can’t suddenly say goodbye to coal”.

“If we switch overnight, millions will go back to poverty,” he said.

PAYING WITH THEIR LIVES

A study published last year estimated that 3.6 million people are directly or indirectly employed in the coal mining and power sectors in 159 districts in the country. State-owned Coal India is also the world’s largest coal-mining company.

But the condition of coal workers “hasn’t improved much” in recent years, observed Bir Bhadar Singh, the vice-president of the Dhanbad Colliery Workers’ Union. Work conditions and facilities were even better 10 years ago, he said.

Despite this, he thinks workers would be worse off if coal mining is stopped.

“If the government can’t give jobs to educated people, how will it give employment to uneducated people or temporary workers who earn their living through coal mining?” he questioned. “If coal mining is stopped, their condition will become more critical.”

Although his home state of Jharkhand in eastern India is resource-rich, it is one of the poorest. Most of the coal-producing states are poor, noted Harjeet Singh, global director of engagement and partnerships at the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative.

And while it may be a cheap way to produce electricity, the mining and burning of coal exacts a huge human and environmental cost.

“Most of the energy or electricity that gets produced goes to the manufacturing sector as well as cities, and people who are into coal extraction are facing the brunt,” said the climate adviser.

“They’re subsidising the production, and they’re the ones who are paying (with) their lives because they live in very high pollution situations.”

There are high levels of coal dust in mining areas, which accumulates in the lungs of people who live and work there, said Vikas Kumar Rana of the district hospital in Dhanbad.

“The dust will cause bronchial asthma and allergic bronchitis. Later, it’ll lead to bronchial cancer,” said the doctor, who sees “many children” who suffer from allergic bronchitis.

He added, however, that the government provides help even to casual workers in the mining industry.

A village health worker can provide medicine to those who need it; if their condition is serious, an ambulance will take them to the medical college or government hospital for free treatment, he said.

AIR POLLUTION A COMPLEX PROBLEM

Air pollution claims well over a million lives in India each year.

It killed 1.67 million people in 2019, with economic losses from the premature deaths and morbidity amounting to US$36.8 billion, or 1.36 per cent of India’s gross domestic product, according to a 2020 report in The Lancet Planetary Health journal.

In the capital, New Delhi, sportswoman Chanchal Yadav began wearing double masks long before COVID-19 surfaced. After moving there in 2016 to continue her training in shooting, she developed allergies and headaches from the choking pollution in winter.

This affected her sporting performance. To cope with the symptoms, the 23-year-old takes medication and anti-allergens and uses saline spray. Doctors have even advised her to leave Delhi to get her health back.

Air pollution makes a move away from coal power needed even more, but the problem is “complex”, said Navroz Dubash, a professor at Indian think-tank Centre for Policy Research.

It is also a problem of transport emissions, construction dust as well as biomass burning for cooking and crop clearing, he cited.

Distant net-zero targets aside, he said India and other countries must act sooner to cut emissions.

WATCH: India’s coal addiction (46:58)

“If we don’t take substantial action in the next 10 years, then you can say goodbye to net zero down the road,” said Dubash, who is also an adjunct senior research fellow at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

The Indian government should provide coal-dependent regions with resources and programmes to make the energy transition, and support workers in coal-related sectors to minimise socio-economic disruption, the experts said.

India’s coal dependence, however, should not obscure its rapid renewable energy deployment. Modi pledged at COP26 that India will meet half its energy requirements with renewables by 2030 and increase its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 gigawatts by then.

Solar power entrepreneur Amol Anand and electric scooter maker Kshitij Kumar are perhaps the faces of India’s energy future. Anand, 33, co-founded Loom Solar in 2018, and the company now employs 100 people and produces 80,000 solar panels a year.

Related stories:

Kumar, 44, is the co-founder of Goreen E-Mobility, which now makes 30,000 e-scooters a year.

What is notable to him is that smaller towns are embracing electric vehicles, and besides Delhi, the most populous state of Uttar Pradesh is also driving vehicle sales.

“We’re seeing a lot of traction in the rural markets… so the transition is happening,” he said.

Even coal scavenger Gauri can see a life beyond the coal pits. “When COVID-19 hit the nation, doctors saved the lives of so many patients,” she said. “I want to study and become … like them.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.

.JPG?itok=97AHNnkd)

.JPG?h=7721c754&itok=cUe3Ld2h)