Micro apartment, granny flat: What affordable housing looks like for Asia-Pacific millennials

Swopping space for savings has become a reality for many young adults who want the convenience of city living but face rising costs. CNA’s Money Mind discovers how three individuals have learned to embrace, and endure, their cramped quarters.

Living small in Tokyo, where there is a growing number of micro flats like this.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

TOKYO/MANILA/SYDNEY: Kazuki Hirata’s Tokyo flat may be 9 square metres — about the size of six tatami mats — but it is home nonetheless, at a monthly rent of 83,000 yen (S$720).

The 31-year-old has learned to sleep diagonally on his futon and leave the toilet door ajar to avoid bumping his knees against it.

He does not mind the squeeze, not when his place is within walking distance of his bartending and sommelier job, which often ends in the early hours when public transport is not available.

“Once I had the furniture put in and started living in it, I didn’t think it was too small,” he said.

More than twice the size of Hirata’s micro apartment is Mark Lorenzo Permalino’s studio loft in Manila. At 22 sq m, it is almost the size of two car park lots.

The 28-year-old dreams of upgrading in two years’ time — to a two-bedroom condominium in Makati, metropolitan Manila’s financial hub, where he resides now.

But cost is the biggest roadblock. The information technology professional found that pre-selling units in an upscale condo scene like Chino Roces Avenue could start at around 12 million pesos (S$272,000) for a one-bedder.

He is making do with his studio for now, adding babyproofers to cover the sharp corners where there is low headroom, which he knocks his head against “more often than not”.

By comparison and by international standards, Rhod-Lee Mercado’s place in Sydney, which has two bedrooms, a laundry room, a separate bathroom and a linen cupboard, does not seem small. It is, however, part of someone else’s backyard.

The 29-year-old resides in a “granny flat”, originally designed as an adjacent living space for grandparents. It offers the amenities of a full-size home, just scaled down.

At 60 sq m, his flat is a quarter of the average floor area of new houses in Australia, which was 237.6 sq m in the 2022-23 financial year.

Saving money was the main reason he opted for a granny flat. “(It’s) a generally cheaper rental option in Sydney for more of what you’re getting in a property,” he said.

With housing affordability becoming a real issue for younger generations in big cities, the programme Money Mind explores how these young adults across the Asia-Pacific navigate the challenges of living small while effectively saving money.

TINY IN TOKYO

Hirata’s flat is the smallest but packs in the essentials, including a laundry corner, a loft bed and even a kitchenette, though it can only accommodate a single cooking pot.

It is less than half the size of a typical Tokyo studio, but rent is about 20 to 30 per cent cheaper, consuming close to a third of his income.

Based on data from real estate company Savills, average rents in the 15 to 30 sq m size band in Tokyo’s central five wards have risen by close to 20 per cent between 2016 and this year.

With inflation and real estate prices also climbing, there may be more small flats to keep rents affordable, said Savills Japan managing director and head of research and consultancy Tetsuya Kaneko.

WATCH: What it’s like to live in a tiny micro apartment in Tokyo, Japan (6:47)

Still, for the space he has, Hirata finds it “a bit expensive” — although living small means a cut in other expenses too. With limited space, overspending becomes impractical, and groceries are about the only items he brings home.

His urge to buy new clothes has waned; instead, he relies on a capsule wardrobe. “I basically wear the same clothes to work (and) even on my days off,” he said. By minimising unnecessary buys, he maximises each item’s use.

Cleaning has also become a breeze. One of the benefits of confined quarters is simplified chores, which saves him time and effort. For instance, he uses a handheld vacuum to clean the loft, and wet wipes for the floor.

Beyond savings and convenience, he has come to enjoy the “cosiness” of his micro flat. “I prefer to … feel surrounded, which is calming,” he said. And he is not alone in embracing this lifestyle.

Real estate developers like Spilytus are building micro flats in sought-after areas, such as Ebisu and Nakameguro. This explains their popularity among young people, who like living in prime locations at reasonable rents, said Keisuke Nakama, the company’s president.

Spilytus, which has been developing these shoeboxes for a decade, reported an occupancy rate of 99 per cent across more than 100 properties, with the majority of tenants aged under 30.

Designed specifically for singles, these micro flats typically see stays of around two years. But for Hirata, four years on, he has no plans to move unless prompted by marriage or a major job change.

MILLENNIAL DREAMS IN MANILA

With his plan to upgrade, Permalino feels less inertia but still faces the issue of housing affordability in Metro Manila, where a new home costs, on average, more than double the value per square metre in areas outside.

WATCH: Savings and side hustles to achieve Filipino millennial’s Manila condo dream (7:17)

Its median home condo price is 25 times the median annual household income — the fifth-highest ratio among cities in the 2024 Asia Pacific Home Attainability Index by the Urban Land Institute.

The lowest house prices are around 4 million to 5 million pesos now, said Marife Ballesteros, vice president of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies. “To afford that, you should be earning (a monthly) income of around 95,000 pesos.”

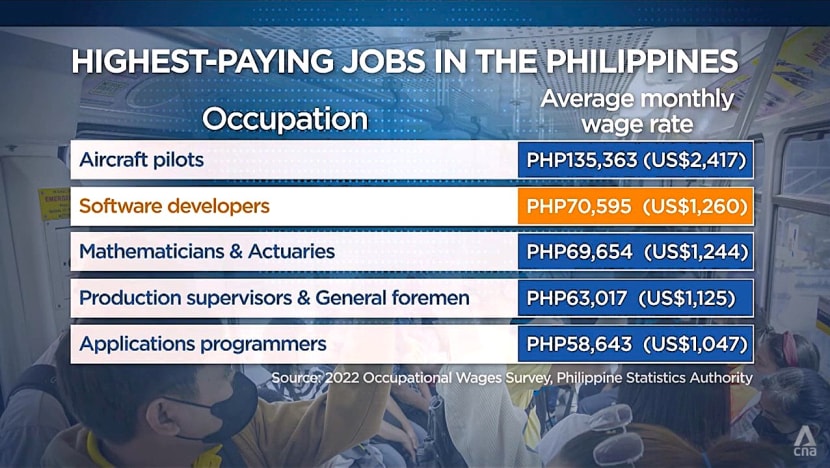

Filipinos across selected industries earn an average of 18,423 pesos, however, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority’s 2022 Occupational Wages Survey.

But younger Filipinos may have better earning potential owing to their technological capabilities and the rise of global job opportunities, which Ballesteros said would eventually enable them to afford larger homes.

For software developers in information services, the average monthly salary is 70,595 pesos, which means a disciplined approach to saving is key.

Permalino remains optimistic. He is working towards saving half a million pesos and is halfway there.

His monthly rent, utilities, transport and food cost about 50,000 pesos, but his YouTube vlogs about Manila life generate nearly 12,000 pesos a month. He also saves 10 per cent of his salary, using digital banks to maximise interest rates.

Looking ahead, he is exploring coding, video editing and graphic design on the side to boost his income and move closer to his goals.

Metro Manila is where he wants to put down roots for the next two decades. For him, the convenience and experience of its city life are worth the costs compared with moving back to his home town of Baguio.

“In the grand scheme of things, you can kind of justify (the higher cost of living), depending on your job,” he said. “In my case, it pays a lot better.”

To find an affordable home, however, he knows careful research is needed. “Everything you see on social media, at least for the advertisements, or on flyers or (from) real estate agents … isn’t (always) what it is,” he said.

GRANNY FLATS A SAVING GRACE IN SYDNEY

Over in Australia, where 31 per cent of Australians are renters, there is an acute shortage of housing.

This has tightened rental supply, and rents are up by almost 40 per cent since 2020 — nearly an eightfold increase over the same period of time before the pandemic.

WATCH: I’m 29 years old, but I live in a granny flat (6:51)

“Australia has simply failed to keep up (its) dwelling construction when it comes to the (number) of people (who) need somewhere to live,” said property data provider CoreLogic Australia’s head of research, Eliza Owen.

“This is most pronounced in Sydney. … We’ve gone from weekly median rents of about A$580 (S$500) at the start of the pandemic to A$780 as of September this year.”

Sydney’s rental vacancy rate has hovered between 1.1 and 1.7 per cent this year. And at first, securing a unit was a bit challenging for Mercado.

His weekly rent of A$650 is lower than the rates for comparably sized units. Living alone, however, he is mindful of energy use to cut his electricity bills, although his internet costs are higher without roommates to share the expense.

The physiotherapy student is taking a year off studies to work full-time and, he hopes, save enough to cover expenses before his student placement next year. So far, he has managed to save about 30 per cent of his income.

“After Covid and when the borders opened again, we found that students and young professionals were more of a profile in the granny flats that we manage,” observed Starr Partners manager of new business and operations Elise Nusco.

Granny flats are cost-effective, but they could come with trade-offs such as reduced privacy. Mercado’s flat, however, is at the front of the property, giving him direct access to the street, plus his windows do not face the shared property.

One drawback he cited is that granny flats are usually located outside bustling commercial areas, which makes them less ideal for those seeking urban excitement. Additionally, secure parking is often lacking, so vehicles are at risk of wildlife damage.

But he has no regrets and no plans to return to traditional apartment living anytime soon.

“I live in a stand-alone building. I’m not sharing any walls with anyone. There’s … more time to myself and less distraction from things in life,” he said.

Watch this Money Mind special here: Tokyo, Manila and Sydney. New episodes every Saturday at 10:30 p.m.