Why Japan’s youth are lonelier than their elders — even embracing solitude, at great social cost

Japanese society teeters between strict self-restraint and sinking into chronic loneliness, with its youth on the brink. The programme Insight delves into the trend towards loneliness and what the country can do to combat it.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

TOKYO: At age 14 she fled her abusive parents, seeking a fresh start in Tokyo, only to find herself ensnared in new troubles.

Moving between children’s homes until she turned 18, Aya (not her real name) found loneliness taking hold. Out on the streets, she became addicted to the warmth and attention offered by the charming, well-dressed men from Tokyo’s host clubs.

“I could think that I wasn’t alone, that they really found me, even for a moment, and that I wasn’t invisible,” recalled the 24-year-old.

This companionship proved to be nothing more than a facade and came at a high price. It left her financially shattered — with a debt of over five million yen (S$45,000) — and still yearning for a genuine connection.

About 130 kilometres away in Naka, a city of about 50,000 residents, 24-year-old Nacchan (not her real name) also feels isolated. The postgraduate student returned to her home town for research and to assist the city hall with town planning.

With one to two hours of free time per day, she struggles to maintain close friendships. Seeing her peers flaunting their sumptuous meals on social media made her feel only more alienated.

“It’s an income that’s impossible for me, and it’s painful for me to realise that I’m different from them,” she said.

Aya and Nacchan may seem worlds apart, but both are lone wolves in a growing pack.

A nationwide survey conducted in 2022 found that 40.3 per cent of the 20,000 respondents “felt lonely” at least occasionally — a rise of 3.9 percentage points from 2021, when Japan’s social distancing measures were still in place.

While loneliness is not entirely unexpected in a country known for its insular social culture, what stands out is that those in their 20s and 30s reported the highest levels of loneliness.

WATCH: Japan’s young are now its loneliest generation, overtaking the old — Why? (46:45)

So the younger generation rather than their elders, it seems, are spending sunset alone, with an increasing number choosing to embrace solitude. The programme Insight finds out why there is this trend and what risks it poses for Japan.

WHEN ONE IS A ‘FUN’ NUMBER

One young Japanese who has stumbled upon the pleasure of her own company is actress-cum-model Ellie Misumi, 26.

While running an errand in Shinjuku and craving a salad bowl, she realised that being on her own meant she could enjoy her meal at her own pace and indulge in her favourite music or videos without interruption.

This epiphany marked the beginning of her “solo katsu” journey, a term that describes engaging by oneself in activities traditionally considered as social.

“(It’s) the perfect time to reflect,” she beamed. “It feels like … I’ve become more mature. And it’s great fun.”

Her experience mirrors the life depicted in Mayumi Asai’s acclaimed essay Solo Katsu Joshi no Susume (Recommendations of a Solo Lady), which inspired a television series of the same name.

The show highlights the life of a corporate employee who relishes activities such as eating alone in restaurants, having her own parties and staying at love motels. It has gained a cult following in Japan over its four-year run.

Very likely solo katsu had resonated with the public owing to pandemic-era restrictions on group sizes, which inadvertently encouraged people to try activities on their own. And when they did, they may have “found it surprisingly fun”, said Asai.

The economy has also taken notice, with more singles-friendly products and services emerging in the travel, housing and finance sectors. Therefore, living alone has never been easier, observed Ai Sakata, a consultant at Nomura Research Institute.

The most extreme form of living alone is embodied by a group known as hikikomori, or individuals who confine themselves to their homes.

For Kyoko Hayashi, the hikikomori lifestyle began when she was 16. What started as school absenteeism evolved into dropping out entirely and becoming a shut-in. She attributes her retreat to the harsh school rules and corporal punishment inflicted back then.

“Why would they resort to violence to suppress children in a school that’s supposed to nurture them?” she questioned. This dissatisfaction led her to coop herself up at home intermittently until her late 30s.

Last year, an education ministry survey showed that almost 300,000 elementary and middle school students in Japan refused to go to school for at least 30 days.

An estimated 20 per cent of these pupils are likely to become long-term recluses, said Tamaki Saito, a University of Tsukuba professor of social psychiatry and mental health.

“Japanese elementary and middle school classrooms have become very oppressive spaces for students,” he added, pointing out that strict regulations on hair colour, skirt length and other appearance-related rules could create a stifling environment.

NOBODY WANTS TO BE A BOTHER

Nevertheless, the self-imposed isolation among youths cannot be attributable solely to ironclad school rules.

According to Hideaki Matsugi, the director of Japan’s Office for Policy on Loneliness and Isolation, a “turning point” occurs when young people graduate, move out on their own and drift away from their school friendships.

Even when they maintain friendships, close confidants are rare. For example, when Misumi shares her frustration over the toxic competitiveness in the entertainment industry, her friends respond with “I see”, and the conversation quickly fizzles out.

“They can’t sympathise. I get told they don’t get it, or they don’t like thinking about it,” she lamented.

It’s somehow ingrained in my mind that even as friends, no matter how close we are, we’re still just separate people.”

Seigo Miyazaki, too, felt that his friends would not understand his struggles, even if he tried to explain.

His mother suffered from the incurable disease, multiple system atrophy. With his sister away at university and his father busy working, he had been caring for her since he was 15 and became her primary carer shortly after high school.

Largely due to his caretaking responsibilities, he deferred higher education and cut contact with childhood friends and his then girlfriend. “I’d feel embarrassed about talking to my friends about my family affairs,” the 34-year-old said.

This reflects a unique aspect of Japanese culture, where people are conditioned to keep to themselves.

Younger individuals in particular tend to avoid getting involved with others, fearing the complications of unfamiliar situations or the burden of dealing with potential problems, observed Mitsunori Ishida, a Waseda University sociology professor.

“Talking to people or doing something with others is seen as a tremendous risk,” he said.

This cautious approach can even extend to family members. Misumi, for instance, suppresses her negative thoughts to avoid being seen in a bad light.

WATCH: Why Japan’s Gen Zs are struggling with loneliness — and yet, they wouldn’t change a thing (7:28)

To avoid bothering others is a tacit social norm in Japan. Hence, when people feel they might be an inconvenience, they often withdraw from social circles, avoiding deeper involvement.

Staying under the radar is less simple in the age of social media and online connectivity. But studies have shown that having online connections in quantity does not translate into quality relationships.

Moreover, noted Ishida, the ease of blocking people or disconnecting means one can still feel insecure and isolated.

Opportunities to socialise offline also diminish as young Japanese enter the workforce now, according to Matsugi.

Japan is known for its long working hours, including large amounts of overtime. While colleagues can offer some companionship, young adults must navigate a post-pandemic working environment where remote work and opting out of social gatherings have gained acceptance.

Marriage is far from a panacea for loneliness, particularly for the ladies. Many Japanese women are still expected to become housewives after marriage, limiting their social interactions outside, said Saito.

Nacchan has rejected this conventional path but still feels left out when she sees her university peers in Tokyo partnering up and settling down. “I’m bothered by these differences, and sometimes I feel that I’m lonely,” she said.

ESCAPING THE LONELINESS LOOP

The thing is, feelings of loneliness can escalate into serious mental health issues — with mental health professionals making a distinction between transient and chronic loneliness, a condition marked by a persistent sense of isolation and the feeling of not belonging.

“It’ll eat up your self-esteem,” warned Roseline Yong, an assistant professor in public health at Akita University. “And that’s the loneliness that’s going to kill.”

It nearly killed Aya. “There were several buildings downtown that girls (in sex work) often jumped off, and every time I passed by there, I kept thinking I wanted to go there and die,” she recounted.

Hayashi had similar thoughts. “I should’ve been going to school or work … but I just couldn’t bring myself to do that,” she reflected. “I kept tormenting myself (by thinking), ‘There’s no point in such a worthless person living.’”

A 2021 study found that compared to economic hardship or pandemic-related social isolation, loneliness had a stronger impact on suicidal thoughts.

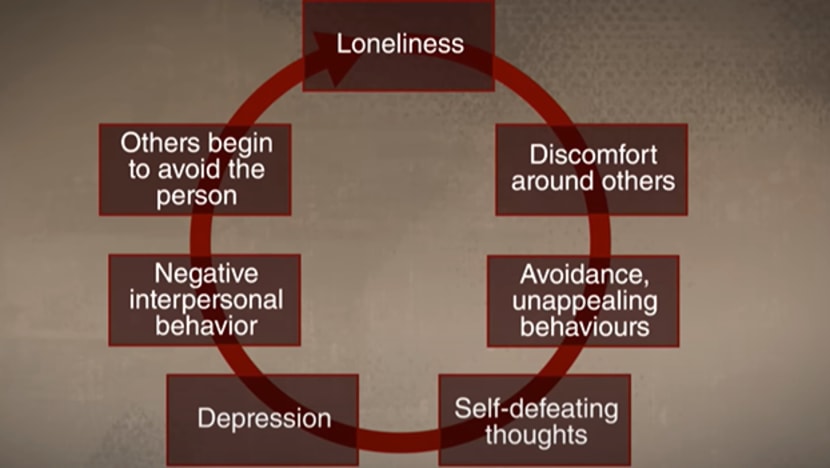

Loneliness can also be self-perpetuating and lead to behaviours or thoughts that foster further isolation, a cycle that psychologists refer to as the loneliness loop.

On top of that, there is a stigma to seeking help for mental health issues in Japan.

When Hayashi was a hikikomori more than two decades ago, support hotlines were virtually non-existent, not to mention people who understood her situation. “So it never occurred to me to seek help,” she recounted.

After she bounced around mental health clinics in her 20s, her physical and mental conditions eventually improved. She also discovered gatherings organised for shut-ins and began attending them.

“I finally met a lot of people who had the same experiences as me,” shared the 57-year-old. “I was able to feel that I wasn’t alone.”

The road to recovery for Japan’s hikikomori is challenging, but things are changing. Hayashi is part of the change, helping to lead Hikikomori UX Kaigi, a support group where they can connect and share their stories.

Similarly, Miyazaki heads the Young Carers Association, where he advocates for others by sharing his own experiences. These non-profit organisations align with the government’s stated goal of creating a society where support and community are easily accessible.

On April 1, Japan enacted a law positioning “loneliness and isolation” as societal issues requiring local governments to establish support groups for those in need.

Some people in urban areas have taken matters into their own hands by returning to their rural home towns.

If people feel there is no “ibasho” — a place where they feel at home — in the city, then the countryside may offer a greater sense of belonging, Ishida noted.

This is true for 29-year-old Naoki Harabe, who, after six years in Tokyo, moved his family of four back to his home town, Yasato.

City folk seemed to him to be reserved, which made it tough to ask for help. In contrast, neighbours in rural towns are more understanding, especially when it comes to the racket his two young children can make.

“No matter how different our … interests may be, when you live close to each other, a connection is born,” Harabe said. “It’s clear to me that this is my home after all — I’ve strongly felt this since returning to Yasato.”

For those remaining in metropolitan areas, such as Aya, life can gradually brighten with patience and positivity.

She paid off her debt and has found her sense of belonging with a non-profit organisation she had reached out to for support after a pregnancy scare.

“Even if you don’t believe it, you’ll have friends as you get older who’ll let you be who you are,” she remarked.

The programme Insight airs on Thursdays at 9 p.m. Watch this episode here. You can also read about how and why Gen Z Filipinos, the loneliest youths in Southeast Asia, are struggling.

Where to get help:

Samaritans of Singapore hotline: 1-767

Institute of Mental Health helpline: 6389-2222

Singapore Association for Mental Health helpline: 1800-283-7019

You can also find a list of international helplines here. If someone you know is at immediate risk, call 24-hour emergency medical services.