For old folks, leaving Tanglin Halt is like losing a kampung family. Can it be replaced?

One of the last few residents in Tanglin Halt, Cheong Mui Chai, 91, is waiting to collect the keys to her new flat at Dawson. Meanwhile she tends to the papaya tree she’s grown. (Photo: Tan Wen Lin)

- Some of the last few residents moving out soon, under a SERS exercise, have lived there for 50 years

- They rely on a community of hawkers, shopkeepers, neighbours and a centre that is “like family” to look out for them

- But with many in this support network not moving to Dawson, there’s worry about how it will affect the elderly

- Part 2 of a package on relocation asks how community and government can help mitigate the pain of relocation

SINGAPORE: At 93, Madam Wong Ying has lived more than half her life in Tanglin Halt.

Her three-room flat on the third floor may be starting to show its age in the stains on the walls, but it is full of her life’s memories – dark wooden furniture, accumulated vases, ornaments, plants and photos. It’s set in familiar surroundings and comfortable routines.

She cleans the floor and tends to her plants on Mondays. Every Wednesday, it’s a leisurely five-minute walk to the Tanglin Halt market to buy food and catch up with her friends. The kindly laksa seller there always refuses to take her money. “I’m scared to go to his stall!” she says with a diffident laugh.

Sundays are for church, one bus stop away. And four times a week, she can be found at the FaithActs centre a short stroll away, playing games and taking exercise classes.

But these days, she’s been seeing fewer and fewer familiar faces at her hangouts.

“Only a few of us are left,” she said wistfully in Cantonese. “The rest have moved.” Soon, she will have to as well.

Her face is stoic when asked about how she feels about relocating. “I don’t want to think about it,” she says.

Wong is one of 3,480 Tanglin Halt households that are being moved as part of the Selective En-Bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS) to rejuvenate older housing estates. The inclusion of Tanglin Halt – one of Singapore’s oldest estates – under the scheme was announced in 2014, and it is one of the largest SERS exercises to date.

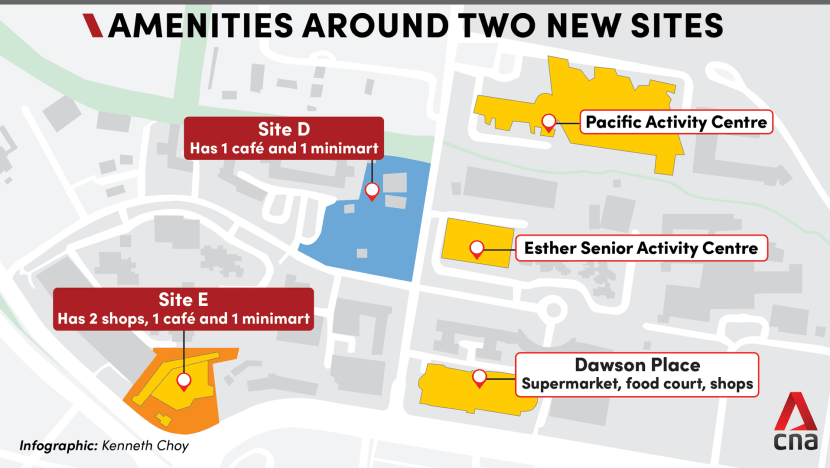

Affected residents are being allocated new flats at five nearby sites, and some have already moved into finished units at Dawson Vista and Forfar Heights, while others are waiting on the completion of the remaining sites – expected by end-2021.

But while this means modern new amenities for residents, some are concerned about how the big move will disrupt long-time social support networks for elderly residents like Wong – and the impact this dislocation could have on their mental and physical well-being, if not properly managed.

CNA Insider tracked some of the elderly residents over two years, including in the wake of the COVID-19 ‘circuit breaker’ which threw into painful relief the worrying effects of social isolation on the elderly.

WATCH: Life uprooted: Tanglin Halt to Dawson, a documentary 2 years in the making (20.38)

Related: Part 1 of relocation lessons

GOODBYE TO CENTRE THAT’S A SECOND FAMILY

When we first met Wong in 2019, it took her just over 10 minutes to walk with slow, mincing steps, using an umbrella as a walking stick, the 600 metres from her flat to the FaithActs centre at 50 Commonwealth Drive.

She never fully recovered from a fall a decade ago that injured her arm and leg. Yet, she made the journey there four times a week for her friends – and the centre’s executive director, Shirley Ng.

For 10 years, Ng has been involved in the day-to-day running of what is a second home for 300-odd seniors (it also caters to youths and families in the estate). Ng has come to regard the old folks as family, and they her.

“They treat me like I’m their child,” she said, warmly remembering how she once casually mentioned that she liked a certain type of salted vegetable – and the next day, she was presented with a big, home-cooked tub of it.

Besides companionship, outings and exercises, FaithActs offers the estate’s seniors vital support such as home visits, cleaning and grocery deliveries for those who aren’t mobile, help to get to medical appointments, and help with reading and translating letters.

So when Ng learnt about the relocation plans, there were worries: How would FaithActs continue to serve those who had come to depend on them? For the centre - which is located in a block of flats unaffected by the SERS exercise – would not be moving with them.

The social service agency’s application for a space to run a centre near Dawson Vista was rejected. It also expressed interest in running a centre near the upcoming flats at Margaret Drive, but has yet to get a reply.

For relocated residents, getting to the centre from their new flats in Dawson estate would mean at least a 20-minute walk – half of it unsheltered, with one major road crossing – or a four bus-stop ride.

It’s not that there are no senior activity centres in the new estate; there are at least two currently. But old-timers like Pok Lian Suan still prefer to make the trip to be with familiar faces, though it’s an arduous trip in her wheelchair, even with a helper.

The 67-year-old with Parkinson’s disease moved in June 2020 to a bright, airy new flat at Dawson, and still returns to FaithActs every week. “I’m very happy (when I go back),” she said. “I get to see my old friends.”

For Ng, it seems a shame not to preserve the bonds and trust that her centre has already built with these seniors. “We go beyond the casual kind of relationship and help them as much as we can,” she said.

That’s the reason why they will tell us every little thing… some even tell us where they keep their keys at home.”

She worries that being torn from support systems they know could affect the old folks’ mental well-being.

“They like familiarity,” she said. “If they are not happy, they’ll get into a bad mood and depression seeps in, and then you get other health issues.”

THE ‘CIRCUIT BREAKER’ LESSON

Nothing threw that point into quite as sharp relief as Singapore’s COVID-19 ‘circuit breaker’ from April to June 2020, and the social restrictions that continued in its wake. The effects of the sudden confinement and loneliness on the elderly have been well documented, and it was no different for Tanglin Halt residents.

When CNA Insider met again with Wong in late August 2020, she had visibly lost weight. Her legs, she said, had grown even weaker after not being able to go out or attend exercise classes at FaithActs.

“I have nothing to do and I can’t sleep so much,” she said. After finishing her chores and eating breakfast, she struggled to fill her days and got bored, even depressed at times.

She was not the only one. Ng knew of others who had deteriorated both physically and mentally.

There are cases where mentally, they’re not as good as before,”

She said: “They’re confined alone at home and their only companion is the television and phone calls. I’m so sad to see them all deteriorating.”

One elderly woman with dementia at another FaithActs centre would call her just to hang up, repeatedly. Previously, the woman would send her videos periodically as assurance that she was well, Ng said.

“When we first told (the residents) the centre was closed, they all felt completely helpless. The main thing was fear: They want to come here because most of them live alone, and if they had problems, there’d be no one to communicate with.”

“And of course, the other thing is that they missed their friends.

Related: COVID-19 and the elderly

During the ‘circuit breaker’, FaithActs made meal deliveries and called up beneficiaries regularly to check on them – “panicking a bit”, she laughs, when their calls went unanswered by those who had taken their hearing aids off.

Those in the new estate also have the Pacific Activity Centre and Esther Seniors Activity Centre to look out for them.

The latter, which is run by Presbyterian Community Services, is keen to reach out to new residents and “help ease them into the community”, said assistant director for senior services Tristan Gwee. But efforts have been hampered by the COVID-19 restrictions.

In response to queries, the Health Ministry said the Agency for Integrated Care “has encouraged and facilitated collaborations” between all three centres, and “FaithActs is working closely with these centres to serve the relocated seniors from Tanglin Halt and help them settle into the new estate”.

Esther SAC told CNA Insider it offers exercise sessions, table games and language classes among other things, and manages the pullcord emergency alert system for elderly residents of some studio apartments.

Meanwhile, Ng says FaithActs plans to make transport arrangements for seniors who wish to continue visiting their centre at Commonwealth.

VANISHING FAMILIAR FACES

In Tanglin Halt, FaithActs wasn’t the only one looking out for elderly folks. Stallholders and shopkeepers have been doing so for decades, in this close-knit community.

The history of Tanglin Halt

One of Singapore’s oldest housing estates, Tanglin Halt was one of the five initial districts within Queenstown, Singapore’s first satellite new town.

The estate got its name from the trains that used to stop at the former KTM station located there.

The distinctive rows of 10-storey flats were completed between 1962 and 1963 and even feature on the back of the old one-dollar note in Singapore’s orchid series.

Take Alice’s Hair & Beauty Shop, run by Alice Tan and open since 1976. The round table in the centre of the salon is a gathering spot for regulars to stop by, sit down for a chat, even peel beansprouts together.

“It’s like one family,” said Tan. “Some will even bring breakfast over for everyone to share.”

Then there is the Chinese medical hall which has been around since 1964.

Second-generation owner Jasmine Zhang says the children and even grandchildren of her regulars continue to stop by to pick up their herbs. They tell her, “You know exactly what I need, what is suitable or not suitable for me to take.”

Market stallholders too, are part of this kampung network. “The old folks come to connect (with us) every day,” said hawker stall assistant Loh Sau Lai. “If they don’t come for a while, I’ll get worried and start wondering why.”

Residents’ Committee (RC) member Alice Lee echoed this. “In a kampong, we feel for one another,” she said. “When you see someone every day and always greet them, then suddenly you don’t see them anymore, you will ask about them or go look for them.

But most of these small merchants will not be continuing with business at the new estate.

It came as a shock to Lee, 73, and her friend Shirley Soh when they looked at a model of the new sites and realised there was no wet market.

“Where can we go if there’s no market?” asked Lee, insisting that buying from a supermarket was not the same. “We are already old, it is difficult for us to travel to Ghim Moh or Redhill.”

They started a petition in 2015 for the wet market to move with them, submitting the signatures of 1,000 residents to the HDB and their Member of Parliament at the time, Chia Shi-Lu.

But as it turns out, most of the stall-owners had indicated that they did not want to move to a new market should one be built. Chia told CNA Insider in a 2019 interview: “Because the support was not even 50 per cent, it was hard for us to justify to HDB to carry on.

Many of the shopkeepers and hawkers were getting old and wanted to retire, explained Kwek Li Yong, executive director of the non-profit heritage group My Community.

Kwek added: “The loss of all these familiar community actors adds to the difficulty (elderly residents) face in acclimatising to their new environment."

Put another way, many old folks depend on these daily social interactions with people in their immediate neighbourhood, because decreasing mobility makes it harder for them to venture beyond it. “When we get older, the size of our social networks get smaller,” said Assistant Professor Yi Huso from the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health.

And when even such nearby touchpoints vanish, that increases the risks of loneliness and social isolation.

“Globally, the evidence is clear - social isolation and loneliness increases all types of physical and mental conditions.

“These include hypertension, heart-related disease, diabetes, obesity, and depression. Even death,” noted Yi.

TRYING TO STAY NEIGHBOURS

For the elderly, good neighbours are often the first line of defence against loneliness and helplessness.

Lee, who serves as RC vice-chairman, looks out for Uncle Mauricio, who is in his 80s and lives alone next door. Once, walking past, she saw that he had fallen.

“I called the police, called the ambulance,” she said. Now, she reminds him to keep his corridor windows open, and listens out for his footsteps which tell her that he has returned home safely.

Mauricio has even entrusted Lee with his house keys, after she caught him standing on plant pots outside trying to reach in through the window to unlock his door. He laughs at the memory of her scolding him in her brisk, no-nonsense manner.

“She’s a fairy godmother,” he said. “Everybody runs to her when they have problems.”

Indeed, inside Lee’s flat is a box full of keys passed to her by relatives and neighbours for safekeeping.

“Uncle always loses his keys,” she sighed, shaking her head. “Then my other neighbour also forgot his, and I stood on a chair to reach through his window… After that, I said it was better to give me the key. I’m already old, I shouldn’t climb up on chairs.”

She is far from the only neighbour who is a source of support. And the HDB’s Joint Selection Scheme (JSS) allows neighbours who want to continue living near one another to jointly choose their replacement flats.

About the JSS

The Joint Selection Scheme (JSS) was introduced in 1996 for households affected by SERS, to help preserve ties between neighbours.

It allows up to six households to jointly select replacement flats. They may indicate their interest in doing so when they register for a replacement flat – typically several months before the selection exercise.

Their selection appointments would then be scheduled one after the other, so they can select flats in close proximity with each other.

That’s exactly what a resident who only wanted to be known as Vivien, 71, and her neighbour of 50 years did. They now live next door to each other in Dawson.

“The main purpose was so we could look out for each other… but in fact, they look after me,” she said.

If they don’t see her that day, they’ll knock on her door to check on her. Every Sunday, she joins them for walks. “I tell you, if I didn’t have my neighbour, it’d be very difficult,” she said, explaining that the layout of the new flats was not conducive for getting to know new neighbours.

“I would be very lonely.”

But not all residents might be aware of how the scheme works. Wong told CNA Insider she didn’t know about it.

Lee and five friends hoped to get flats on the same floor – but they wanted units of different sizes which the block didn’t have. (Three eventually got units in the same block, while the others, and Uncle Mauricio, got flats in the next blocks.)

According to HDB, 13 per cent – 434 of the 3,252 Tanglin Halt households that registered for a SERS replacement flat – applied for the JSS.

Former MP Chia noted that moving house is possibly the “most stressful thing that could happen” to a person, with many studies ranking it above a death in the family. “And if you look at some of the studies on what mitigates this stress… I think it’s these neighbourly connections.”

MINIMISING THE DISLOCATION

One non-profit group, My Community, had noticed how that stress of tearing up roots had affected the elderly in other relocation exercises.

In previous SERS exercises in Queenstown, the group had visited residents to collect their stories and artefacts. What was evident was their “very strong emotional attachment” to the place, said group leader Kwek.

“I was talking to a long-time resident. You don’t expect grown men to cry, but while he was recollecting his memories of the old Queenstown Town Centre, he just cried uncontrollably,” he said.

And so, in 2018, My Community set up a “cultural mapping” team in Tanglin Halt to collect residents’ stories and chart their social networks. The idea was that once they had moved, there would be a community museum in their new estate where they could meet up with their old group of acquaintances, to reminisce and look at old photos.

But volunteers also noticed that residents were very anxious about a more immediate concern – the impending move itself. They were “not clear about what’s going on”; some couldn’t read the official letters they had been sent.

This anxiety, Kwek said, was “heart-wrenching” to witness. “Some of them just see SERS as an end point in their life,” he said. “But that’s not what relocation should be – it should be a happy thing, because they’re going to move to a brand-new place with a fresh lease and a better living environment.

In response to queries, HDB said it had taken “great care to design a process to handhold our residents through the entire process”, given that many were elderly. On the day of the SERS announcement, it said, officers did door-to-door house visits to explain the scheme and address concerns they might have.

Each household was also assigned a “Journey Manager” to guide them throughout the SERS process from start to finish.

Nevertheless, Kwek said volunteers often encountered confused elderly residents: “The most frequent questions were ‘I don’t know when I’ll be moving’ and ‘I don’t know what to do’.”

To give residents more support, My Community has launched a befriending scheme, called the Hello Dawson Relocation Programme, where volunteers go door to door and offer to help residents with things like reading official letters, moving and packing.

After the move, many have needed help settling in. Lee and RC volunteers check in on them, offering decorating or space-maximising advice, or directing them to activities where they can make new friends and reconnect with old ones.

The area’s new MP since July 2020, Eric Chua, says there will be “quite a bit of easing in to do” to familiarise them with the area, like “where they can relax, and the bus services they can use”.

A BETTER WAY FORWARD?

The sizeable role that volunteers have been playing in the Tanglin Halt relocation exercise echoes what happened at Dakota Crescent back in 2016, when residents of the ageing rental estate were resettled at Cassia Crescent.

There, too, grassroots volunteers as well as a group of young heritage enthusiasts – much like My Community – were invaluable in helping the old folks who were bewildered and struggling to cope with the big move into a new environment.

It has led some to ask if there is a better way forward, as more estate renewal exercises loom in Singapore?

What parties involved in both the Dakota and Tanglin Halt relocations agree on, is that the sheer scope of all the issues involved means that it cannot simply be the Government’s responsibility to deal with the social dislocation caused by the process.

The Government cannot do this alone, nor can the ground do it alone,”

said Sim Bee Hia, a grassroots leader who chaired the Dakota Crescent relocation taskforce.

“A resident who is forced to relocate would see the HDB officer as someone that is on the opposite site,” she added. “But when a volunteer team comes in to hold (the residents’) hands, we can help to mitigate issues.”

The HDB too acknowledges the need for “many helping hands”, given its own constraints on resources such as manpower, and aims to “work more closely with institutional and community partners” for future relocation exercises.

Also calling it a collaborative effort was Lim Jingzhou, who founded the Cassia Resettlement Team which has been assisting residents in the new estate since 2017. But he noted that the work of supporting communities undergoing relocation is “not something that can be done for free”.

“We might require people who are doing this on a full-time basis, to be able to do it effectively and sustainably,” he said.

Assistant Professor Ng Kok Hoe of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) suggested providing volunteer groups with more support and funding.

Another idea mooted: A dedicated agency to look purely into relocation issues. Kwek said it could be a “joint community effort” between the authorities, community groups, MPs and residents themselves. “Each of us has our own capabilities to contribute to a relocation programme.”

Ultimately, LKYSPP’s Ng stressed that it is important that everyone takes an “active interest” in the various issues thrown up by the relocation of elderly communities – as most HDB residents will experience relocation “at some point in their lives”.

“We should also be concerned about relocation for our most vulnerable citizens,” he said

EPILOGUE: FROM RELUCTANT, TO LOOKING FORWARD

For now, the COVID-19 pandemic has meant a delay to the final chapter of the Tanglin Halt story.

MP Chua had hoped to hold a “farewell event” early next year to give residents a sense of closure, but plans might have to wait on the easing of COVID-19 restrictions.

The relocation timeline has also been affected because of the impact on HDB’s Build-To-Order projects in general. Lee, whose new flat at Margaret Drive was originally expected to be completed by the end of 2020, was notified that there’d be a delay.

She had spent much of the ‘circuit breaker’ period last year staring out of her window at the bright-lit windows of the new flats in the distance, anticipating the big move. Other residents who were initially reluctant to shift out have also changed their minds.

“At first, they thought they would be sad when they moved out,” Lee said. “But after applying for the flats… everyone also wants to move.

Some of the old people have asked me, ‘I’m already so old, can I move there before I die?’”

Vivien too had once longed to stay on in Tanglin Halt for sentimental reasons. But after moving into her new flat at Dawson, she admits she’s changed her mind. “Everything has to come to an end,” she said.

“It’s a blessing that I’m here now … everything is new, and as I unpacked, I realised that I needed to throw away a lot of my things.”

Wong, however, is still in limbo. After recently suffering a fall, she has been living with her sister; her family plans to get her a live-in helper when she finally moves into her new flat at Margaret Drive.

The 93-year-old could return to her Tanglin Halt flat later this month. But the joy of being home again will be bittersweet: It will be to start packing up her belongings, with the help of FaithActs. In a few short months, she will have to move again.

This is the second of a two-parter looking at how the impact of relocation on the elderly can be better managed, as more estates are marked for redevelopment. Read part 1: The move from Dakota to Cassia.