Trolls for hire in Philippines: The concealed political weapon used in a social media war

Trolling has become lucrative for more than a few Filipinos, and it went into high gear for this year’s Philippine elections. The programme Undercover Asia gained access to the shadowy networks spreading falsehoods for politicians.

Online engagement has been crucial in reaching Filipino voters. Increasingly, however, social media in the Philippines has become a breeding ground for disinformation.

MANILA: It is an “easy job” she has done full-time since the pandemic. All she needs is a SIM card and she can work from home, or anywhere for that matter.

Sharon (not her real name) does not know who her bosses or fellow workers are, however. She is “not interested” in knowing them either.

“What’s important is we get our pay cheques, and we deliver on what they ask,” she said.

Her job mission: To spread lies to as many people as possible. Using fake profiles — and various SIM cards, as a matter of fact — to infiltrate social media groups, she has a daily target of at least 150 shares.

Sharon, who is in her early 30s, is a paid troll. She is part of a large troll army available for hire in the Philippines, where politicians have allegedly shelled out for manipulating political discourse and swaying public opinion.

A troll in the Philippines can potentially earn anywhere between 30,000 to 100,000 pesos (S$740 to S$2,480) a month, according to news reports in the country.

That makes trolling financially lucrative compared with the average monthly wage rate, which was about 16,500 pesos across all monitored occupations and industries in 2020.

And this is how “politicians are weaponising disinformation now”, said De La Salle University professor of communication Jason Cabanes.

“It’s not just one camp, but many different political camps. Everyone seems to be in on it. They feel that they need to be part of this new political game.”

It is a social media war. And as it went into high gear for this year’s Philippine elections, the programme Undercover Asia gained access to these networks of disinformation, in a look at the unseen force behind the country’s politics.

WATCH: Internet trolls — the unseen force behind Philippines’ politics (46:06)

THE TROLL

According to a report by humanitarian organisation Mercy Corps, political disinformation campaigns play out in three phases: The development of core narratives; onboarding of influencers and fake account operators; and dissemination and amplification on social media.

In Sharon’s case, she said she received instructions to “promote a certain person” on social media for the election season.

“Our leaders suggest joining groups that have more than 3,000 members. The ones we joined have 50,000 members,” she said, citing the Facebook pages of overseas Filipino groups, for example, and the “broken-hearted groups”.

To get as much engagement as possible, she targets their emotions.

“I reply sarcastically so they get more emotional when they respond,” she said. “That’s our strategy. That’s the better way to encourage more comments.”

Her job supports her family financially, but they do not exactly know what she does. “They know that I’m busy commenting on social media,” she said. “But they don’t know the real agenda of my work.”

Three years ago, she was working in a hotel in Manila. And her introduction to the work of a paid troll came from a colleague who happened to be one herself.

“I’m still doing this job as it’s helped me a lot financially, especially during the pandemic,” said Sharon.

THE ‘ARCHITECT’

Paid trolls are at the bottom of the money tree, however. Cabanes estimates that most of the money — around 75 to 80 per cent — remains in the pockets of the “chief architects of network disinformation”.

These masterminds were identified in a 2018 report titled “Architects Of Networked Disinformation: Behind The Scenes Of Troll Accounts And Fake News Production In The Philippines”, which he co-authored.

“They’re mostly ad and PR people. And some of them (are) … former journalists,” said Cabanes.

Through connections in the local media, Undercover Asia tracked down a chief architect, “Rosa”, who agreed to speak by phone on condition of anonymity.

“Usually, in our industry, (and) specifically for our team, there’s no need for us to approach certain politicians,” she said. “It’s the other way around. They need us more than we need them.”

She said she runs an independent public relations agency and had been hired by two candidates in the presidential elections.

“We implement national campaigns, usually parallel to their official operations,” she said. “We complement this and amplify this on social media.

“Perhaps it could involve artificial boosting of followers (and) content. We can also create pages in support of the person or groups.”

Her political clients prefer to pay in cash, using local currency, she said.

A “minor social media engagement” for a “local client from a key city” could range from 300,000 to 500,000 pesos a month, while “moderate” operations for a “national client” could range from 800,000 to a million pesos a month.

Asked if her political clients are aware that she hires people to spread disinformation to help them, she replied: “Exactly why they’re hiring us.”

It is a growing international business, she noted. “There are troll farms … in China, in Russia, in Croatia, in the United States and the Philippines.

“Every country has its own share of keyboard (armies). Denial of such would be a lie.”

THE INFLUENCER

The disinformation is amplified by digital influencers who are armed with unique skill sets. “Their role is to kind of translate this … conceptual strategy into actual posts, actual memes, comments that’ll become viral. So that’s their expertise,” said Cabanes.

Take, for example, “Brandon”, who used to work in the television entertainment industry, where he sharpened his skills in content production.

He said he was hired to create videos to boost a congressman’s popularity among voters and hurt the rival candidate’s credibility.

“No problem for me even if I’m called an online troll, as long as I’m getting paid,” said the part-time influencer in his 30s. The employer he works for full-time, however, is unaware of what he does for additional income.

Brandon used to produce “travel and inspirational content” on a Facebook page that he co-created with a friend in 2019. With 98,000 Facebook followers and 2,000-plus YouTube followers, they made some money from their non-political content, he said.

But they realised they could earn more by creating and sharing disinformation.

About 80 per cent of their viewers were Filipinos aged about 29 and over, male and female, so the social media page became a medium for politicians targeting a local audience.

“What I’m doing is wrong … But during this pandemic, when everyone’s in a time of need, I’d choose to support my family knowing that I’m not the only one doing this,” said Brandon, the main breadwinner.

“Many people are doing this. Too many.”

He said he knew vloggers and YouTubers who were “supporting their respective candidates” by providing content “just for money” during the election season. “Many politicians are indeed using (them),” he added.

THE FORMER FACEBOOK EMPLOYEE

Irregular behaviour on social media does not go unnoticed, however. For example, a YouTube channel called Showbiz Fanaticz built a following based on celebrity content but then switched to videos focused mainly on politics.

“We’ve seen that being used to basically bait audiences … and grow the reach of YouTube channels, Facebook pages and so on,” said Gemma Mendoza, one of the pioneers of news platform Rappler, where she spearheads efforts to address digital disinformation.

Rappler’s research has led her to conclude that politicians are buying and hijacking these social media pages for the purpose of pushing disinformation.

One way to discern such manipulation on Facebook, for example, is to click on the transparency tab of the page to see if a group has changed its name, she advised.

Such groups were among a network of more than 400 Facebook accounts, pages and groups that parent company Meta Platforms took down 33 days before polling day in order to tackle disinformation.

A former employee based in Manila, who did not want his identity revealed, said that Facebook accounts should be authentic and that those reported as suspicious would be reviewed.

Part of his job was to monitor and identify these accounts, and “Andy” cited some of the protocols for combating trolls. For example, the authentication process requires one’s phone number and email address to be linked to one’s Facebook account.

And to counter trolls who buy multiple SIM cards and register multiple accounts using different phone numbers, Facebook users are identified by their Internet Protocol (IP) addresses to track where the accounts are created.

If the IP address is the same but there is a new contact number, that account would be disabled, said Andy.

Even without the system filters, he can spot trolls and inauthentic accounts, he added. They do not use their own pictures, for example, and there is no account activity other than comments.

On presidential candidate Leni Robredo’s official Facebook page, Andy pointed out a commenter who “only (had) 14 friends”.

Still, tech companies are struggling to keep pace with disinformation networks that are becoming more skilled in covering their tracks.

“What (social media platforms) are looking for is co-ordinated inauthentic behaviour. But … it’s not co-ordinated because (disinformation networks) distribute the work to different people who don’t necessarily know that they’re working on the same project,” said Cabanes.

“It’s these kinds of disinformation tactics that are well thought of that often evade regulations … and that’s a real big concern.”

THE LAW (OR LACK THEREOF)

There have been paid trolls in the Philippines as early as 2016. A year after his election, then President Rodrigo Duterte admitted to hiring trolls during the 2016 campaign period.

Mercy Corps noted the use of Facebook, for example, to reinforce positive narratives about his campaign and to silence critics.

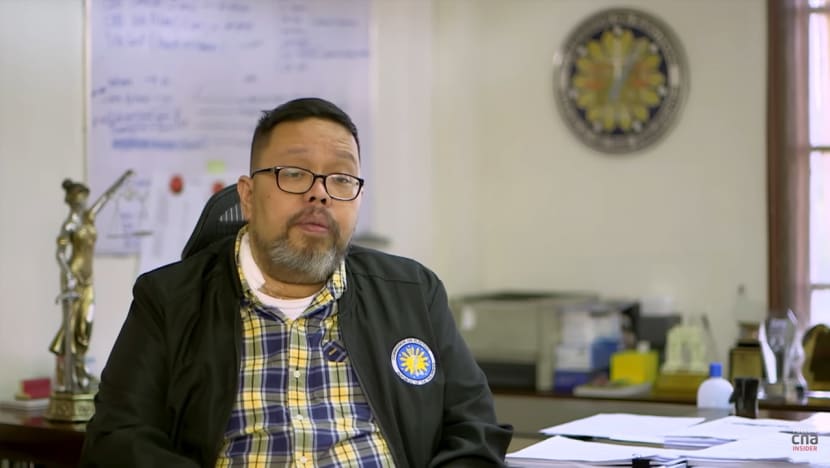

Even with paid troll activity becoming more widespread since then, the Commission on Elections has not taken legal action “because there’s no law that penalises trolling in the Philippines”, said James Jimenez, its current director for education and information.

“Other than that, … there’s no easy way to identify these trolls,” he said. “A single person can have as many as 10 separate accounts, with 10 fully formed identities. And that’d be very difficult by itself to police.”

Candidates have to declare their campaign spending, but this has not proven effective in exposing the hiring of paid trolls.

“We imagine the use of money for disinformation would be drastically under-reported, if reported at all,” said Jimenez. “While, technically, there are very few laws that penalise it, everyone knows that it’s bad. And no one would cop to it.”

He believes the government must “step up with new laws”. He added: “Law enforcement has to be abreast of new technologies as well … especially since enforcement has a very technical component.”

THE TROLL HUNTERS

For the moment, however, investigative journalists in the country are the ones hunting trolls.

“We noticed as early as November last year that there seemed to be something off with some of the trending hashtags in relation to (Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’) Marcos (Junior),” said Don Kevin Hapal, who leads Rappler’s digital forensics team.

“The hashtags that (were) specifically promoting Marcos Jr and attacking critics … were mostly created around October, around the same time, which was extremely suspicious.”

Another group of journalists, who founded non-profit news organisation Vera Files, has also been monitoring disinformation campaigns since last year. They found that Marcos Jr “benefited the most from (election-related) disinformation”, said Vera Files online verification team head Celine Samson.

“He benefited a lot from disinformation about his father’s accomplishments or … that all the ill-gotten wealth cases against the Marcos family have been dismissed.”

Vera Files also noticed that Robredo became the “biggest target of disinformation” over the months of campaigning. “A lot of fake quote cards … were attributed to Robredo, made to look like she’s incompetent or she makes nonsensical statements,” cited Samson.

On YouTube channel Showbiz Fanaticz, there were videos accusing Robredo of being behind a petition to prevent Marcos Jr from running, as well as a video claiming that hackers were planning to commit electoral fraud against him.

To help fight against such disinformation, Tsek.ph, a three-year-old pioneer in fact-checking — an initiative of 34 partners from academia, media and civil society organisations — was revived in January for this year’s elections.

There was “a lot of disinformation … to make candidates look like they were disqualified” or that there was “massive cheating going on”, observed Tsek.ph co-ordinator Rachel Khan.

To provide the public with verified, up-to-date information, the group uploaded fact-checked content on its website. Members of the public who detected any piece of disinformation could also inform the group to get it fact-checked.

THE COST

The war against paid trolls comes at a price, however, for journalists like Hapal.

“Whenever we publish stories that expose disinformation … those networks would fight back,” he said, citing messages he has received from strangers who were “making fun of my photos (or) calling me a paid journalist or … other derogatory remarks”.

I was not only flooded with these threats and attacks via private messages, (but) they were also posting my photos everywhere.”

The disinformation networks had been co-ordinating their attacks for more than a year before the elections, according to Khan. “It’s been more of a long-term effort to mislead people.”

While the allegations of disinformation marred the election campaigns, there is no data that proves falsehoods influenced the outcome of the presidential election directly.

On May 25, the Philippine Congress declared Marcos Jr to be the winner with 31.6 million votes, or nearly 59 per cent of the total vote. That was more than double the number of votes for his closest rival, Robredo.

His camp declined requests for an interview with Undercover Asia. He has, however, publicly denied using trolls in his campaign.

In a post-victory event, he made a mock admission of guilt as seen in a YouTube video. But there has been no other evidence that he had hired a troll army.

What remains apparent to Rappler’s Mendoza is that no matter which politician, online disinformation threatens democracy and weakens confidence in public institutions.

“Democracy thrives in a space where, first of all, you have to agree on the facts and then you debate … And there needs to be, at some point, a consensus,” she said.

“Right now, what’s happening is people are being driven into tribes in echo chambers, so there’s no room for debate (and) consensus. It all becomes ‘I’m right, and you’re wrong’ … That isn’t conducive for democracy.”

Watch this episode of Undercover Asia here.