Are BPA-free plastic bottles really safe? Here’s what you need to know

Reusable plastic bottles and food containers may carry a BPA-free label but are they as safe as claimed? The programme Talking Point investigates whether they still leach chemicals that affect our bodies and looks at some alternatives.

Bottles labelled “BPA-free” have flooded the market in recent years. But how safe are they really?

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Look at the bottom of any reusable plastic container or bottle you have bought in recent years, and it is likely you will see a label declaring it “BPA-free”.

Indeed, BPA has developed a bad reputation over the years. It is known as an endocrine disruptor, and many scientists believe it can cause cancer and reproductive harm.

“Simply put, (it’s a chemical) that can mimic certain hormones or block certain hormones,” said Ben Ng, an endocrinologist at Mount Elizabeth Novena Specialist Centre. There is a worry, he added, that long-term exposure can affect children’s growth.

BPA (short for bisphenol A) can be found in many household items. It is used to make polycarbonate, a hard plastic that looks and feels like glass but is light and nearly unbreakable.

While it is found in items like clothes, toys and even thermal paper receipts, Ng said “more than 90 per cent of our exposure to BPA comes from ingestion”, that is, from plastic food containers and bottles that could leach chemicals into food and drinks.

While Singapore’s food regulations stipulate that all food packaging imported for use in Singapore do not migrate any harmful substances to the food, there is no specific ban on BPA.

Canada, however, banned BPA from baby bottles in 2008. The European Union followed suit in 2011. The United States Food and Drug Administration prohibited BPA in baby bottles and sippy cups in 2012 and infant formula packaging in 2013.

In the years since, BPA-free products have flooded the market.

But how are these bottles made? Are they really safe? As the programme Talking Point discovered, the replacement chemicals in some BPA-free bottles may also get leached out — and affect human health in a similar way to BPA.

WATCH: Are BPA-free plastic water bottles really safer for your health? (22:11)

WHAT IS IN YOUR BPA-FREE BOTTLE?

BPA-free bottles often replace BPA with other bisphenol compounds that are structurally similar, such as bisphenol F (BPF) and S (BPS).

But these bottles are not necessarily safer than BPA bottles, said Tong Yen Wah, a National University of Singapore (NUS) associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

“Some of these bisphenol-type compounds could still leach into the drinking water. And we could be drinking (them).”

To find out if this is the case, Talking Point sent 11 reusable bottles from a variety of brands for a laboratory test. The bottles were made from different materials, including three types of plastic, stainless steel and glass.

Nine of the bottles had a BPA-free label. The remaining two were labelled “food-grade”, which meant they were safe for food storage.

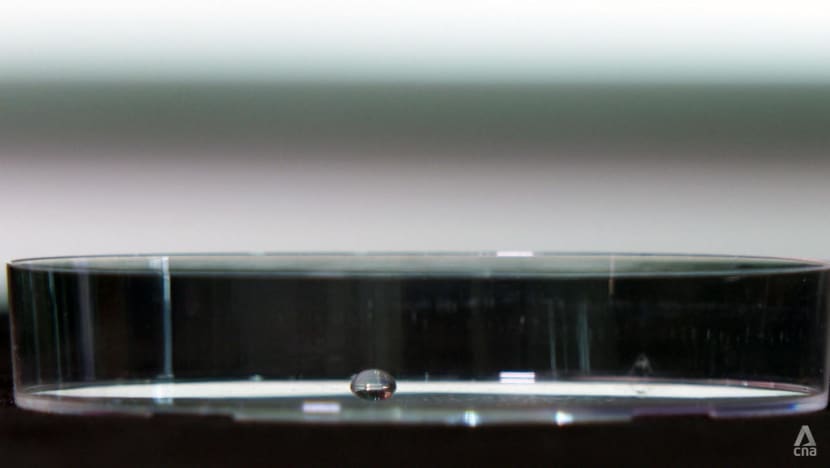

The bottles were filled with water at room temperature for two hours to test for leaching of bisphenols into the water.

The results showed that four of the bottles leached small amounts of replacement BPA chemicals. Three of the four bottles — including the two labelled “food-grade” — were made of polycarbonate. The fourth bottle was made of polypropylene, another type of plastic.

There was no leaching of any bisphenols from the remaining bottles, which were made of stainless steel, glass and a plastic called Tritan.

The amounts of leached chemicals, however, ranged from around 10 to 20 nanograms per litre to about 70 to 80 nanograms per litre.

These are “really minute” concentrations, said research assistant Mauricius Marques Dos Santos from the Nanyang Technological University’s Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute. A nanogram per litre, he said, is equivalent to one drop in 16 Olympic-size swimming pools.

But when the test was repeated with hot water, more bisphenol chemicals leached into the water — three to four times more, depending on the brand of bottle.

ARE THESE CHEMICALS SAFE?

To further understand the safety of these replacement chemicals, the leached chemicals were tested on human cells. While the test revealed nothing toxic enough to kill the cells, it showed that the chemicals had a similar effect to BPA.

“Inside the human cell, we can see that there’s enough of the chemicals present to begin to activate (the) estrogen receptor system,” said Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute executive director Shane Snyder, who led the lab investigation.

“In other words, the cells are responding to the estrogens from the chemicals that leach from the bottles.”

The chemical concentrations are still “quite low”, he added. “You’d have to drink from a lot of bottles to have an effect based on what we see so far.”

For example, one would have to drink eight times the amount of water from the bottle that had the most leaching — at 80 nanograms of BPS per litre — to see a significant estrogenic effect.

Nonetheless, US-based journalist Abigail Davidson said research in the past 25 years has shown that endocrine-disrupting chemicals “don’t always follow that typical belief system of ‘the dose makes the poison’”.

That means that when we’re exposed to even low doses of endocrine disruptors, that can still have an effect.”

Davidson, editor of The Filtery, a website aimed at helping consumers reduce environmental toxins at home, added that while there is less research done on other bisphenol compounds such as BPS and BPF, “most of the information is consistent with the results from BPA”.

“The chemical structures are so similar that they’re going to have similar effects in the body.”

In response to queries from Talking Point, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) said that currently, “no harmonised international standards on bisphenols in foodstuffs” have been established. There is also “no conclusive evidence” that BPA alternatives are unsafe.

“Nevertheless, the SFA is closely monitoring international scientific discussions on the safety of bisphenols and periodically reviews our safety requirement while keeping abreast of the latest developments,” stated the agency.

WHAT SHOULD CONSUMERS DO?

There is, however, some good news for consumers, said Davidson, who highlighted bisphenol’s “pretty short” half-life: about six hours. This refers to the time taken for a substance to halve its original dose in the body.

“If you do start trying to reduce your exposure, you can really make a difference pretty quickly,” she said.

One way of doing this is to look for safer alternative plastics, such as Tritan, which did not leach any bisphenols in the Talking Point lab test.

This plastic is a co-polyester “developed as a safe alternative to polycarbonate”, according to Seager Inc retail merchandising manager Liew Yue Ci, whose company is the exclusive distributor of Nalgene bottles in Singapore — bottles made from Tritan.

Tritan shares similar characteristics with polycarbonate, such as clarity, durability and resistance to impact, said Liew. But it is BPA-free; and it costs more.

While some Tritan bottles are labelled as such, Nalgene bottles carry only the “BPA-free” label, Liew added. “Consumers should be aware of what they’re buying and also do their own due diligence.”

In a consumer advisory shared with Talking Point, the SFA said consumers should use reusable bottles or food containers according to instructions. For example, only containers labelled microwave-safe should be used for reheating food in the microwave.

A product should be replaced when its integrity has been compromised, such as when it is cloudy, discoloured or cracked.

When choosing reusable products, consumers can also opt for other materials, such as glass, porcelain or stainless steel, especially for hot foods and liquids.

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.