From Seoul to Singapore and beyond: The flight of South Korea’s wealthy and what’s at stake

Seoul’s slide down the global millionaire rankings reveals deeper anxieties, while experts warn of a ripple effect on the economy. CNA’s Insight looks at the factors that could decide whether rich South Koreans stay or go or even return.

Seoul has been a magnet for wealth, from luxury stores to luxury cars, since the 1980s. But it is starting to lose its lustre — and its millionaires.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SEOUL: Sitting comfortably in his Singapore office, millionaire Ken Lee reels off the names of his main clientele — Korean giants such as LG, Lotte, Samsung and more.

Out of all his firm’s consulting services, however, what sets him apart is a niche that has grown over the years: helping wealthy South Koreans relocate abroad.

He has moved almost 50 of them to Singapore, says the managing director of Lee Kim Alliance, adding that these are people with a net worth ranging from US$10 million to “a few hundred million dollars”.

When he himself migrated two decades ago, only a small number of high net worth Koreans were moving overseas. But today, the enquiries are multiplying.

His firm typically gets about five relocation enquiries “every year”, he says. In the first half of this year, there were about 10 enquiries.

This is but a small part of a growing trend: Seoul’s status as a magnet for wealth is on the wane.

In the Henley & Partners list of the world’s top 50 cities for millionaires, South Korea’s capital fell five spots to 24th — the steepest drop in the latest rankings.

In fact, Seoul’s millionaire population has decreased from 97,000 in 2022 to 66,000 last year.

Across the country, about 2,400 millionaires are projected to migrate this year, which is double last year’s figure and is the fourth-highest millionaire outflow globally. Relative to population size, South Korea has the second-highest proportion of millionaire emigrants.

Their departure has wider implications for the country. There is a ripple effect on the middle class as the wealthy are “key movers” of investment, consumption and job creation, says Kang Minwook, associate professor of economics at Korea University.

Financial firms typically define “wealthy” as having financial assets exceeding 1 billion won (US$700,000), and some 461,000 people fell into this category at the end of 2023, estimates the KB Financial Group.

They form 0.9 per cent of the Korean population but hold 58.6 per cent of the total financial assets of Korean households. About 70 per cent of them are in the Seoul Metropolitan Area.

“I view the departure of wealthy individuals for other countries as a bad sign for the South Korean economy,” says Kang.

“These individuals care not only about their current wealth but also about their future assets, so their decision implies that investing in Korea is no longer worth it.”

Seoul was once a magnet for those chasing upward mobility and wealth. Why is it losing millionaires, and what would it take to get them back, asks the programme Insight.

WATCH: Seoul is losing millionaires. Why does it no longer attract the rich? (45:45)

WHY THEY’RE PACKING THEIR BAGS

For many of those heading abroad, the driving forces include high taxes, political instability and lifestyle pressures.

The country’s top income tax rate stands at 45 per cent, while inheritances above 3 billion won are taxed at 50 per cent.

“That’s one reason why wealthy individuals are looking abroad,” says Lee Yoonsoo, a professor of economics at Sogang University. “When they get older, they want to pass their assets to their children.”

Their choice of destinations reflects their priorities. “Dubai is probably for asset protection,” he cites, highlighting its safe banking system and zero income tax.

Vancouver and Los Angeles have very big Korean communities, good schools and real estate investment (opportunities).”

Other popular destinations include Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. “Compared to Seoul, they provide better quality of life in some cases,” he adds. “The most important things are the stable tax environment and global networks.”

Migration firms in Seoul are busier than ever. “Last year, we had 100 families join us to start their (United States) immigration process,” says immigration attorney Yuree Lee of Kookmin Emigration Corporation.

“In the first half of this year, we surpassed that number.”

Pessimism about South Korea’s prospects is another push factor. According to Hana Bank’s 2025 Korean Wealth Report, 74.8 per cent of its wealthy survey respondents expected the economy to worsen this year.

“They see … business-friendly environments and the growing opportunities (outside the country),” says Lee Yoonsoo.

Ken Lee agrees. “Nowadays, the Korean economy is a bit down. (It’s) also politically a bit unstable,” he says. “That’s the reason why a lot of people come to (Singapore).”

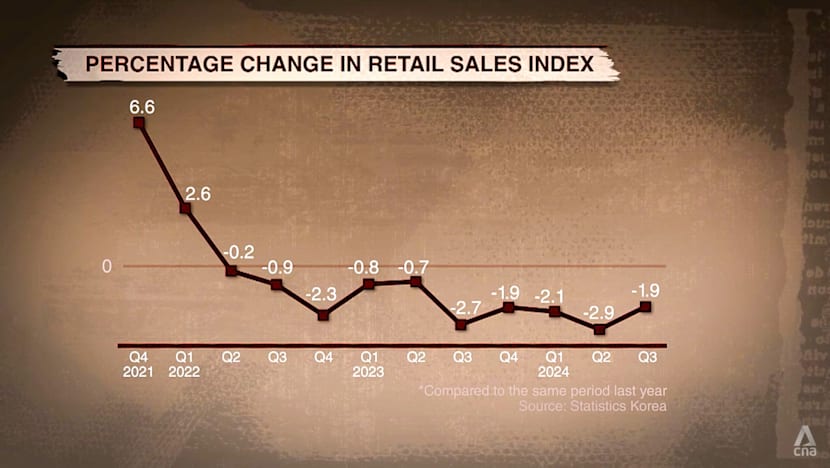

The economy has struggled since the start of the pandemic. Household debt has hovered above 90 to 100 per cent, weighing on consumption. Retail sales are in a three-year slump, the longest since the data was first compiled in 1995.

After last December’s martial law crisis, the won tumbled to its lowest against the greenback since 2009, during the global financial crisis. And the outlook for exports, the country’s traditional growth engine, is now cloudy amid global trade uncertainty.

With these headwinds, keeping assets in South Korea has cost the ultra-rich. The collective net worth of its 50 richest people this year dropped to US$99 billion from US$115 billion last year, reported Forbes.

The strains are also visible in the property market. “Because we deal in high-end residential properties and … offices in Gangnam, the departure of the wealthy isn’t great for my business,” says real estate agent Kim Jun-gon.

“Rental prices decrease, but there’s no demand and so the real estate market continues to decline. … Korea is becoming an environment that’s less appealing to the wealthy.”

WHY SEOUL MAY NOT SEE MANY NEW MILLIONAIRES

Among middle-class South Koreans, meanwhile, there is pessimism about moving up the ladder. A Korea Development Institute survey in 2023 found that only 30 per cent of respondents believed their children would have a higher socio-economic status than themselves.

“Upward mobility is becoming hard,” says Lee Yoonsoo, adding that young people are most concerned about paying higher tax rates to support the older generation as the population ages and declines.

For 26-year-old Cho Hanbin, who entered the workforce over a year ago and earns a little more than 50 million won annually — “a bit more than (his) peers” — the goal is to achieve millionaire status by age 40.

But he fears it is an uphill battle. “Maybe only people in their 60s who are retiring from a big company … will be able to achieve this,” he says.

He tried investing, but that has been rocky. “I suffered quite a bit of losses,” says the credit management manager, citing how stocks tanked after the recent political turmoil.

Property, which has long been a ticket to wealth in South Korea, has become harder to access. Housing prices in Seoul rose more than 16 per cent between January 2023 and this April.

“Apartments are the most important investment vehicle in Korea, so … (young adults) push their borrowing to the max,” says Lee Yoonsoo.

Even so, “they can’t get into the very affluent areas of Seoul, where the price appreciation is the highest”. And they feel “they can’t catch up in the housing market”, he adds.

Many of Cho’s peers, meanwhile, are struggling to find a job. According to a Korea Enterprises Federation survey, only 60.8 per cent of companies planned to hire new employees this year, the lowest figure since 2022.

Some 565,000 young Koreans (aged 15 to 29) have remained jobless for more than a year after graduation, and about 230,000 of them have been looking for employment for more than three years, data from Statistics Korea showed in July.

Many of them will have to depend on contract work, which may offer “low salaries and three-year contracts”, says Lee Yoonsoo.

As you get older, you should get (a higher) salary. But if you stay in a contract job, and your growth profile isn’t good, then those young people won’t make as much as their parents made.”

Cho, who is working on contract, agrees. “I’m looking for a permanent position so that I can continue working (with a measure of) stability,” he says. “I also tried to … live on my own, but this keeps getting delayed.

“I think our generation will become poorer than our parents.”

As the middle class struggles with stagnant incomes, the precarity of jobs, rising housing costs and investment setbacks, South Korea may not see many new millionaires anytime soon.

KB Financial Group’s annual Korea Wealth Report shows that the number of South Koreans with financial assets exceeding 1 billion won rose 10.9 per cent to 393,000 at the end of 2020 but by only 1 per cent in 2023.

CAN SEOUL APPEAL TO THE RICH AGAIN?

Since June, however, South Korea has had a new leader, President Lee Jae Myung, with new plans for the country’s future — his election victory coming after his predecessor, Yoon Suk Yeol, was impeached for the martial law fiasco.

“When a new president takes office, there’s a sense of hope,” says Korea University’s Kang.

The Lee administration’s 31.8 trillion won stimulus package was approved in July, and a task force was launched in August to develop a mid- to long-term economic growth strategy.

“If we redefine policy direction,” says Kang, “Seoul can transform into a city favoured by the wealthy again.”

The country’s ageing population remains a big challenge, however. Already, 20.3 per cent of South Koreans are aged 65 and over. This figure is projected to exceed 40 per cent by 2050.

Almost 40 per cent of these seniors are living in relative poverty, that is, living on less than half of the median income. It is the highest rate among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

The Bank of Korea has warned that each percentage point increase in the elderly population will reduce the effect of state spending on gross domestic product growth by 5.9 per cent.

“So the GDP growth of Korea will be a lot worse as time goes on,” says Lee Yoonsoo, adding that fiscal spending on welfare and pensions will increase even as the tax base shrinks.

And spending tax money on helping an “ever-increasing” number of seniors is not what the rich want, says Woo Yoonseuk, the vice president of strategy at the Korean Association for Policy Studies.

Indeed, following an investor backlash against plans to hike corporate tax and expand capital gains taxation, the Lee administration has rolled back on the latter proposal. Last month, the president also ordered that additional inheritance tax relief should be given.

Yet, the complexity of South Korea’s inheritance tax rules is partly why it “lags far behind its peers in attracting wealthy individuals”, says Lee Yoonsoo. “And the … visa system isn’t suitable for rich people to reside in the longer term.”

In the region, Malaysia, Thailand and Japan have introduced golden visa and long-term residency schemes, he highlights. “And Singapore leads the race with low taxes.”

Much is at stake for Seoul as other global cities also vie to attract the rich. The total investable wealth of South Korea’s migrating millionaires this year is US$15.2 billion, estimates Henley & Partners.

Will they return anytime soon? Ken Lee, for one, turned a secondment into a 20-year stay.

“If I go back, … (with) all the wealth I’ve accumulated in Singapore, I’d have to pay half in Korea when I pass my wealth to my daughters,” he says. “I just regularly visit Korea. … I don’t think I’ll go back.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.