Why are so many eateries in Singapore closing? Owners cite rent, manpower, competition

Hundreds of eateries are vanishing every month. As Greenwood Avenue stalwart Ka-Soh bids farewell too, the programme Talking Point meets its third-generation owner and others to find out why, and how small players can survive.

Employees of Burp Kitchen & Bar tearing up as its owners announce the eatery’s closure.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: An era is ending on Greenwood Avenue. Ka-Soh, the 86-year-old Cantonese “zi char” stalwart that once drew the likes of Hong Kong’s Four Heavenly Kings, will serve its last bowl of fish soup on Sep 28.

“Defeated” is how Cedric Tang, Ka-Soh’s third-generation owner, feels. “(Though we) have worked so hard for so many years,” he says, “we’ve had enough.”

It was a decision “forced” on him by a “tornado of factors”, the strongest of which is a looming 30 per cent hike in the rent when the lease is up this year.

To pay about $15,000 a month, up from about S$12,000, he said he would need to sell 300 extra bowls of fish soup noodles each month on average.

Raising prices, meanwhile, is out of the question. “For heritage businesses, we try not to increase our prices so much because we want to remain accessible to our long-time customers,” he says.

Instead, Tang has rolled up his sleeves, manning the middle line in the kitchen and even washing dishes in a bid to cut costs. But thrift has its limits. Ka-Soh now joins the ranks of Singapore’s food and beverage casualties.

Among them are Burp Kitchen & Bar, another family-run favourite that was one of 320 closures in July, and the Prive Group, which closed all its restaurants as of Aug 31, a month that saw 360 closures.

More than 3,000 F&B businesses shut last year — about 250 eateries each month on average — which was the highest number in almost two decades.

“Even the fittest can’t survive at the moment,” says former restaurant owner Chua Ee Chien, observing that two restaurants in the Michelin Guide Singapore closed within weeks of this year’s edition coming out.

In a two-part special, the programme Talking Point finds out why so many eateries are bowing out and what it will take to keep local outlets from being struck off the menu.

JUST A CASE OF GREEDY LANDLORDS?

For many owners including Ka-Soh, rent is the culprit, though it is not the only one or necessarily the main one.

“Within our community, a majority of tenants have reported increases (in) rentals (of) between 20 (and) 49 per cent,” says Terence Yow, the chairperson of Singapore Tenants United for Fairness (SGTUFF), which represents more than 1,000 F&B and other business owners.

“This is something that we’ve not seen over the past 15, 20 years.”

A healthy turnover of eateries is normal, but what is happening now is “unprecedented”, he adds.

WATCH PART 1: What’s killing our F&B businesses? (23:13)

Following recent cooling measures for residential purchases, shophouses in particular have become hot property among investors, both local and foreign, which has “translated into correspondingly high expectations (for) rental yields”, Yow cites.

Yet, landlords face pressures of their own.

“If somebody’s rent is being renewed now, three years after COVID,” says Ethan Hsu from Knight Frank Singapore, “then even with a 50 (to) 100 per cent rent increase, it may not be … where the market level is right now.”

According to the real estate specialist, construction costs have since gone up by about 30 per cent and maintenance costs by at least 10 per cent.

“A lot of people are fixated with this idea of a greedy landlord, which is kind of sexy,” he says. “The reality is that rent is only one component of the costs that the tenants are faced with.”

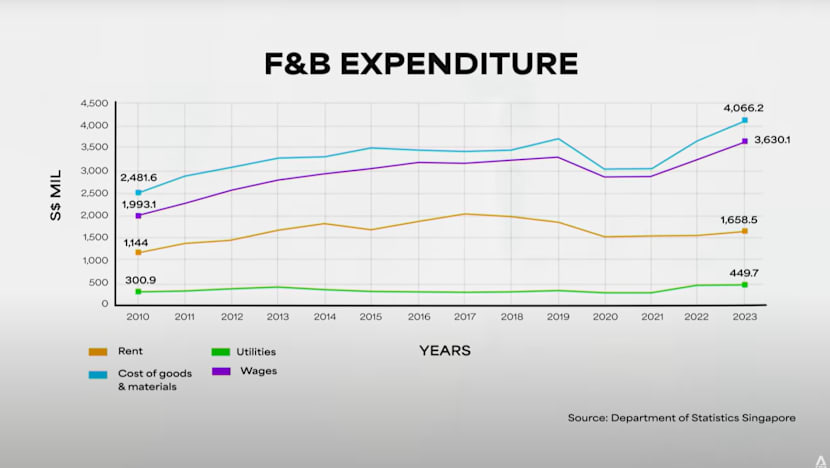

And those costs are higher than ever. At Burp Kitchen & Bar, rising manpower costs coupled with a drop in demand brought it to the breaking point.

With a shrinking pool of cooks, bigger players were dangling up to double the normal pay to secure staff. A smaller outfit like Burp Kitchen could fight for only so long, even after raising salaries and trimming hours.

The Restaurant Association of Singapore sounded the alarm in March on a “serious manpower crisis” and called for foreign worker quotas to be reviewed. But authorities see the crunch as a problem of oversaturation.

Singapore was bursting with nearly 23,600 retail food establishments as at last year, up from almost 17,200 in 2016. While 3,047 businesses closed last year, almost 3,800 new ones opened. Deep-pocketed chains, however, are elbowing out small independents, says Chua.

According to the Department of Statistics’ F&B Services Index in June, caterers and fast-food outlets enjoyed a year-on-year sales increase, whereas restaurant turnover decreased by 5.6 per cent. Cafes, food courts and other eateries saw a 0.1 per cent decrease.

“It’s a drastic change that we’ve observed in customer behaviour,” says Burp Kitchen co-owner Ronald Chye, referring to the drop in spending.

“There are so many choices out there,” adds his wife and co-owner Sarah Lim. “The frequency (with which) you’d see a person coming … dropped from three, four times a week to maybe once a month.”

For Tang, the impact goes beyond balance sheets. “I’ve known (my staff) for 20 years,” says the 40-year-old, “and to lose that part of friendship … (is) not easy to deal with.”

RECIPE FOR SURVIVAL?

When it comes to discovering new restaurants, more than half of Singaporeans — including 59 per cent of Gen Z — rely on social media, showed a 2023 survey produced by hospitality technology firm SevenRooms.

And there are professionals who help F&B operators to sharpen their online presence. Talking Point roped in one, Craft Creative co-founder Dylan Tan, to work with 62-year-old Christopher Lim, who runs Marie’s Lapis Cafe in Bedok North.

It has been five years since the cafe started serving handmade Peranakan food and desserts, passed down through generations.

“We’re just surviving … on a tightrope,” says Lim, who sold his house and cashed out his Central Provident Fund savings as well as his insurance policy to keep his cafe alive.

Under Tan’s guidance, the cafe rolled out short videos highlighting its heritage and signature dishes.

Lim was also encouraged to post on social media at least once a week, actively reply to comments, launch occasional promotions and eventually team up with influencers or host themed events.

After two weeks, the cafe was booked up for its Sunday lunch service — and the month ahead too. Business jumped by about 30 to 40 per cent, and Lim is determined to “keep that going”.

Still, likes and shares cannot fix all problems. Member of Parliament for Holland-Bukit Timah GRC Edward Chia, a former F&B owner himself, has called for short-term increments in the number of foreigners businesses can hire.

But he also sees the need to help small businesses “find ways to improve productivity” with the same number of staff “or perhaps even (fewer)”.

WATCH PART 2: How can we help small local restaurants survive? (23:43)

Some businesses are already adapting. Third-generation “zi char” chain Keng Eng Kee Seafood has invested in customer relationship management software and membership systems.

“These (give us) feedback (on) how we can improve (customer) experience,” says co-owner Paul Liew, 44. “We also find out certain (staff) preferences … to help decrease the resignation of employees.”

Chia believes small businesses could also benefit from human resource support such as a chief HR officer as a service, where certified HR practitioners can serve several small and medium enterprises at once, which makes it cost-effective.

Tenant groups like SGTUFF, meanwhile, are lobbying for fairer rental in the form of rental renewal caps pegged to inflation or gross domestic product growth.

“(This ensures) that after a tenant has put … two or three or more years (of) effort (into) building the business,” Yow says, “that tenant isn’t subject to a sudden, big 50, 60, 70 per cent hike.”

WATCH: Our last day as a restaurant — What made us give up after 11 years (9:40)

Even when a business faces closure, it is not always the end. Tang, for example, will try to pivot towards a home-based business selling frozen fish soup.

“With this frozen soup, he’s attempting to enter the market for … a new crowd,” says his new business partner, Park Tan. “So it’s a bit different from what his grandfather left behind.”

But for Tang, the revamp is his way of continuing his family’s legacy. “It’s also an opportunity to regrow and rebuild,” he says.

Watch part one and part two of this Talking Point special. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.