Social network founder turns champion for exploited farmers in Indonesia

Three months after the launch of farm-to-home app RegoPantes (or “fair price”), farmers are already seeing their income nearly double. Is this the future of grocery shopping in Indonesia?

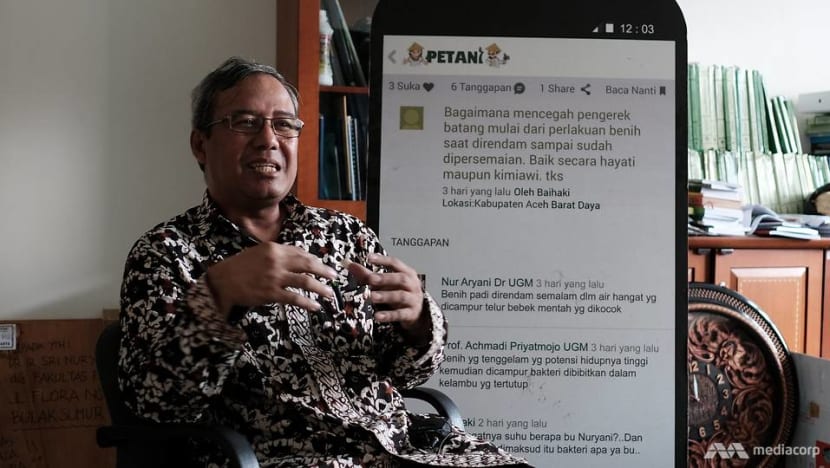

Sanny Gaddafi is the co-founder of RegoPantes, a farm-to-home app that helps small Indonesian farmers sell their produce at better prices by cutting out the middlemen. (Photos: Ray Yeh)

BEKASI, Indonesia: The bustling city of Bekasi, located on the eastern border of Jakarta, has a long history dating back to the fifth century. But demographically, it boasts one of Indonesia’s youngest populations - an attractive asset not just to the sizable number of multinationals based here, but also for local startups.

8villages is a young tech firm that moved here two years ago. The three-storey building it occupies is not much to look at from the outside. But inside, it buzzes with a youthful, creative energy.

Dressed mostly in casual tops and jeans, the majority of the programmers in this open office are in their early twenties. A few are younger still, in their late teens. Their laptop screens are filled with mind-boggling codes only an experienced computer engineer can comprehend.

It is hard to imagine what this young, tech-savvy bunch has to do with rural farmers who live hundreds of thousands of kilometres away.

But the fact is, their work closely intertwines.

EXPLOITED BY MIDDLEMEN

Agriculture is a key sector in the Indonesian economy, accounting for 14 per cent of its gross domestic product.

Roughly 1 in 3 Indonesians are farmers. Some work in large plantations, and some whose land is less than 0.25 hectare in size are categorised as small farmers.

They are also some of Indonesia’s poorest people - making up no less than 30 per cent of the country’s low-income earners.

“The main issue is their farm size,” says Dr Achmadi Priyatmojo, a professor from the faculty of agriculture in Gadjah Mada University. “The land area is simply too small to generate enough income for them."

But that is just one problem. Even for those owning bigger plots of land, earnings from their harvests often fall short of potential.

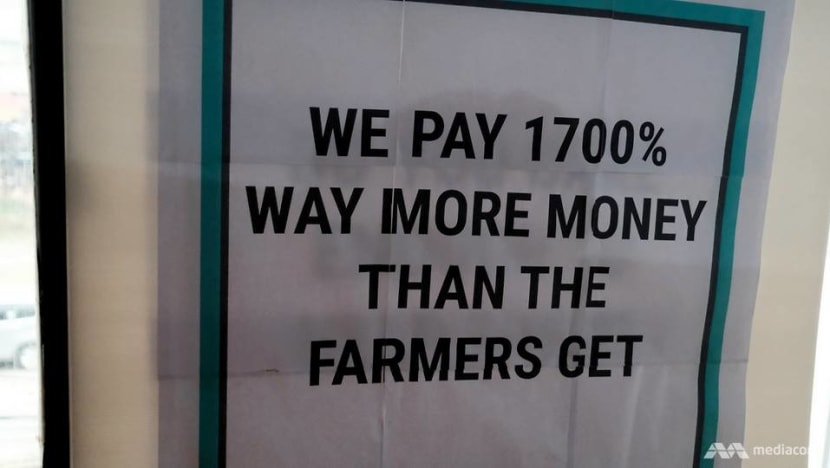

The cause? Farmers’ heavy reliance on middlemen who act as the bridge between them and consumers.

To maximise profits, these merchants pay farmers as little as they can. They do it either by colluding to suppress the prices of perishables, or exploiting the fact that the farmers - many of whom borrow money to buy seeds and fertilisers - are indebted to them.

It is a vicious cycle of poverty that small Indonesian farmers have found hard to break -until now, thanks to a smartphone app developed by 8villages’ young coders.

RegoPantes, which means “fair price”, is a new way to sell - and shop for - groceries that bypasses the middlemen.

The app is an unexpected departure for its co-founder, Sanny Gaddafi, 37, who previously founded one of Indonesia’s most successful social networks when Facebook was still in its infancy.

SOCIAL NETWORK FOR FARMERS

The year was 2004. Sanny was still a university student, and Friendster ruled the social networking space. “As a programmer, I tried to create the Indonesian version of it,” he says.

His social networking project, called FUPEI (Friends Uniting Program Especially Indonesian), managed to register 200,000 users in just two years, an impressive feat back then. Venture capitalists from the United States came knocking on his door.

But the 2009 global financial crisis sent them packing. And Sanny was left wondering: What next?

That was when an acquaintance - French agronomist Mathieu Le Bras, who was based in Jakarta at the time - suggested: “Why don’t we build a social network for farmers?”

That, Sanny says, “felt like a slap on the face”, because he had actually grown up with the children of farmers in Bekasi, and had witnessed their plight firsthand.

“Some got hooked on drugs and overdosed,” he says. “One friend became the security guard of a mall built on the land his parents used to own.”

I was always looking outside Indonesia for ideas. But this guy from abroad tried to convince me to see the problems we can solve inside Indonesia. It totally made sense.

EMPOWERING FARMERS THROUGH INFORMATION

The pair founded 8villages in 2012 to empower farmers by giving them “good information” including agricultural best practices and market prices.

Due to the lack of 3G signal in rural areas, the first platform they built was an SMS-based service called LISA (Farmers’ Information Service).

Subscribers were put into communities based on location and the crops they grow. They received farming tips daily. They could also send in questions that would get answered by experts, all without the need for an internet connection.

Many external partners got involved: Teachers and students from universities, workers from humanitarian organisations, and officers from the Ministry of Agriculture.

Telcos were also roped in to defray the cost of sending and receiving SMSes.

LISA turned out to be a sounding success.

And when the farmers became better at farming, producing better crops in larger quantities, they started to ask the experts: How come I am not earning more?

That was when the problem of the middlemen came into sharp focus for them.

FAIR PRICE FOR CROPS

Two years ago, Le Bras left his role at 8villages to return to Europe, making Sanny the CEO.

“I’m more on the product development side,” says Sanny, “so I had to look for another partner good in business.”

He found that in Wim Prihanto who has a background in agricultural studies. He joined the company as COO in 2016, after pitching Sanny the RegoPantes idea.

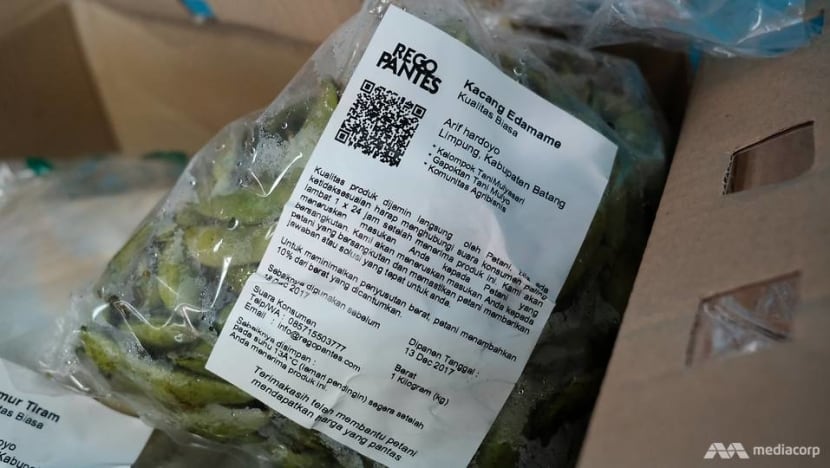

How it works is simple: Before harvesting, farmers post information about their crops on the platform. Consumers hit ‘buy’ and pay. Fresh produce then gets delivered directly to the customers shortly after harvest, without going through middlemen.

And how does the app determine a “fair price”?

“In the offline world, we survey farmer price and market price,” says Mr Wim. “And then the numbers go through a formula to determine the fair price.”

By dropping the middlemen, farmers earn more, yet customers pay less.

But the concept of a farm-to-home smartphone app is not new, even in Indonesia. Two features set RegoPantes apart from their competition.

Firstly, they do not earn through commission, for that would essentially make them the new middleman.

Secondly, consumers can browse each farmer’s profile and decide which ones to buy from. “It is the social awareness that buying is helping,” says Wim.

Sanny adds: “The communities that we approach really want to understand more about the farmers. And if they want to visit them, they can do it, because we show the farmers’ locations.”

GOOD EARLY FEEDBACK

The RegoPantes app went live in September 2017.

To date, seven rounds of shipment have been made to over 100 customers. And around 700 small farmers have signed up as suppliers.

WATCH: How the app is changing farmers' lives (5:11)

As demand goes up, these numbers are expected to increase rapidly. For one, early feedback from farmers appears promising.

Farmers also like that they receive payment upfront through the app, unlike selling to middlemen or supermarkets which can defer payment for up to two months, creating cash flow problems for them.

Reactions from consumers seem equally encouraging.

Buying directly from farmers means they get cheaper and fresher produce, with the added convenience of home delivery.

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Moving forward, the RegoPantes team's immediate hurdle is to get more farmers onboard so that the app can offer consumers more choices, making it truly useful.

To make that happen, mobile phone signal in rural areas and the availability of smartphones to farmers are two pressing issues the firm is working with the government and telcos to address.

In the meantime, farmers share their gadgets. “Maybe only 10 or 20 per cent of farmers have the smartphone,” says Wim. “They borrow a smartphone from their friend and put in their own SIM card. One phone but SIM cards, so many. We call it ‘gadget-tethering’.”

EXPANSION PLANS

Much work also still needs to be done in educating farmers about packaging and delivery. Right now, RegoPantes helps in these areas. But eventually, Sanny wants all farmers to be self-reliant.

Otherwise, given the size of Indonesia and the many islands that comprise it, expansion beyond the West and Central Java regions will be difficult, to say the least.

And Sanny has high hopes.

“At 8villages, we are trying to modernise the villagers by modernising the way they think, so that they become more professional farmers and good decision makers,” he says.

“Or at the very least, they will know how to use technology better.”

Mr Sanny Gaddafi was nominated by reader Rury Demsy as an #InspirAsian. If you know an unsung hero whose story deserves to be told, tell us at this link, or leave CNA Insider a message on Facebook.