Is the US creating an Indo-Pacific version of NATO to deter China?

Amid the Ukraine crisis, China warns of a similar tragedy in Asia as it accuses the US of ‘bloc politics’ in the region. The documentary When Titans Clash examines Beijing’s claim and concerns — and the possibility of a future war.

Marines from Indonesia and the United States taking part in an exchange programme. (Source: US Defence Department Video and Images)

SINGAPORE: It was last June when a British destroyer entered Black Sea waters claimed by Russia since its 2014 annexation of Crimea. In response, Russian Coastguard fired shots into the distance.

Days later, the warship joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) naval exercise in the region involving 32 countries and co-led by the United States and Ukraine.

Some analysts point to events like this as examples of Russia’s fear of NATO and claims of provocation, and of why the military alliance was one of President Vladimir Putin’s justifications for war on Ukraine.

The Chinese government’s narrative also attributes responsibility for the Ukraine crisis to NATO and the US — while other governments and analysts deem the invasion of Ukraine illegal and say NATO expansionism is not a valid reason for invading a country.

Amid the unfolding crisis, China has gone further and drawn a parallel between NATO and the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy announced by the Biden administration in February.

Chinese State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in March: (The strategy) seeks to maintain the US-led system of hegemony, undermines the Asean-centred regional co-operation architecture, and compromises the overall and long-term interests of countries in the region.

“The perverse actions run counter to the common aspirations of the region for peace, development, co-operation and win-win outcomes. They’re doomed to fail.”

Key thrusts of the new US strategy include a free and open Indo-Pacific; supporting India’s continued rise and regional leadership; strengthening the Quad; strengthening extended deterrence with Japan and South Korea; expanding US Coastguard presence; contributing to an empowered Asean; and closing the region’s infrastructure gap.

As regards China, the US stated in its strategy paper that Beijing’s “harmful behaviour” — coercion, aggression and undermining of human rights and international law — spans the globe but is “most acute” in the Indo-Pacific.

At his recent annual media briefing, Wang did not mince words either, saying the US’ strategy in the region is “becoming a byword for bloc politics”.

“The US professes a desire to advance regional co-operation, but in reality it’s stoking geopolitical rivalry,” he said, citing moves like “peddling the Quad”, piecing together Aukus and “tightening” bilateral military alliances.

“This is by no means some kind of blessing for the region but a sinister move to disrupt regional peace and stability.”

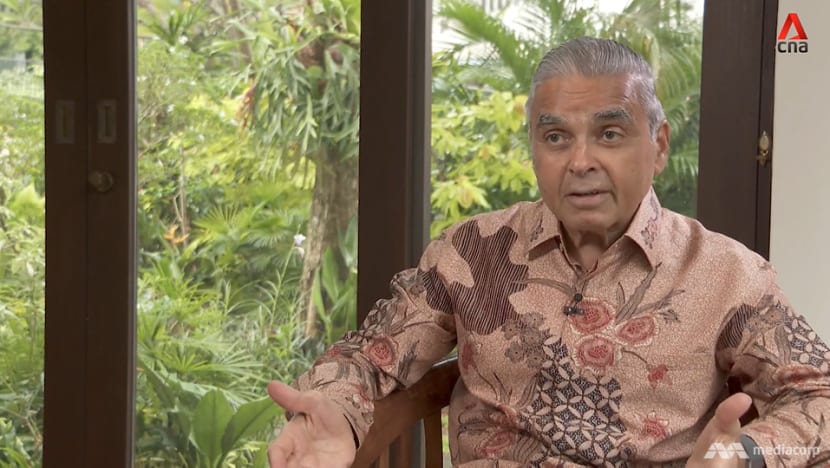

To former Singapore diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, one thing is “very clear”: The “biggest geopolitical contest of all time … has just broken out between the US and China”.

“Whenever a major geopolitical contest breaks out, watch out. There’s definitely a danger of war,” he told the programme When Titans Clash.

That’s precisely why everybody has to be very careful and work hard to avoid the war before it breaks out. And we mustn’t put our head in the sand like an ostrich and say, hey, everything’s okay. No, everything isn’t.”

AUKUS

Last month, China further warned of a Ukraine-style “tragedy” for Asia in the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy.

But in Australia, one of the country’s top intelligence chiefs warned instead that China was intent on establishing “global pre-eminence” and that its “troubling” strategic convergence with Russia would pose new threats to liberal democracies.

When Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison spoke about this possible new world order, he said: “A new arc of autocracy is instinctively aligning to challenge and reset the world order in their own image.”

In that speech, he also unveiled plans to build a submarine base on the country’s east coast to support its future nuclear-powered submarines. The cost: More than A$10 billion (S$9.57 billion).

Related story:

To some, the announcement marked an acceleration of the 18-month evaluation process that was launched following the Aukus agreement signed last September for the US and Britain to assist Australia in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines.

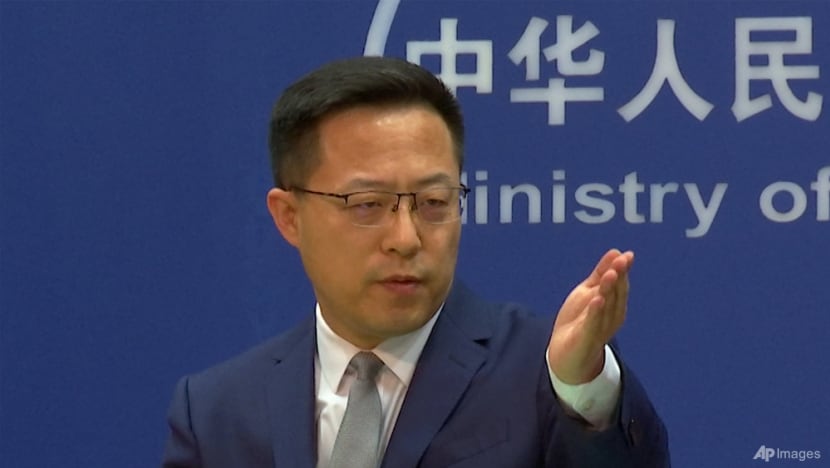

To China, said Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian a week after the announcement, the Aukus co-operation could “create nuclear proliferation risks and shocks to the international non-proliferation system, induce a new … arms race, and undermine regional prosperity and stability”.

Australia is a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and party to the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.

The country has “benefited hugely from this”, noted Victor Gao, vice-president of the Beijing-based Centre for China and Globalisation. But the Australian government “wants to deprive the Australian people of their rare privilege of living in this bubble”, he said.

“This is dangerous for the Australian people as well as for countries and peoples in our part of the world.”

But Charles Edel, the Australia chair at the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), said setting up a nuclear-propelled submarine fleet is not a “gateway” to nuclear weapons and that the Aukus partners “won’t continue if it is”.

He noted that Aukus has “broad bipartisan support” in Australia, a country where 84 per cent of its people do not trust China to act responsibly in the world, according to the latest annual poll by think-tank Lowy Institute.

And as China continues to build up its military forces, “what’s happened in the South China Sea hasn’t stayed in the South China Sea”.

“They’ve continued to push outward and further down … We’ve seen multiple attempts by the Chinese to do a similar spate of building (projects) that they conduct in the South China Sea in the South Pacific,” he cited.

“We’ve seen discussions … about whether or not there’d be a dual-use military-commercial base in Papua New Guinea, in Vanuatu and even just this past month in the Solomon Islands. All of these are much closer to Australia.”

To better protect security in the region, countries should rather focus on “developing patterns of co-operation and interdependence”, said Mahbubani, who spearheads the National University of Singapore’s Asian Peace Programme.

He cited the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership — the world’s largest free trade deal — which entered into force in January and counts Australia and China among its members. “Submarines are stealthy, but trade agreements are stealthier,” he said.

THE QUAD

What is “somewhat of a mystery” to Mahbubani is the Quad, comprising Australia, India, Japan and the US.

“The four countries deny that it’s aimed against China. But the perception is that it’s against China,” he noted. “It creates this rather strange situation.

“Which is why, if you notice, not many other East Asian countries have volunteered to join it … It’s therefore important for the members of the Quad to explain what exactly the endgame of the Quad is.”

The Quad is officially known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. There are joint military exercises in parallel with the dialogue — such as Exercise Malabar, which began in 1992 between the Indian and US navies.

Japan joined the naval exercise permanently in 2015, and Australia participated for the second time in 2020.

Today, Quad co-operation includes climate change action, counterterrorism and infrastructure development. Its members have also collectively pledged to donate at least a billion COVID-19 vaccine doses globally by year end.

“Three or four years ago, it would’ve been focused more on maritime security,” noted Stephen Nagy, a senior associate professor in the department of politics and international studies at the Tokyo-based International Christian University.

“Today, the Quad has evolved to focus on the provision of public goods … connectivity aid to Southeast Asia and South Asia and … investment in the selective diversification of supply chains throughout the region.”

Without a shift away from “a security view of the Quad”, he said, the alliance “isn’t going to get buy-in” from countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam.

In Southeast Asia in general, the Quad has had a mixed response.

The “main concern” was that the Quad “would heighten tensions in the region, especially vis-a-vis China”, said Lynn Kuok, Shangri-La Dialogue senior fellow for Asia-Pacific security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

But with its moves away from “its more militaristic elements” and towards “areas that Asean cares more about” such as pandemic recovery — which demonstrate “sensitivity to the region’s needs” — she thinks “the position on the Quad dialogue has softened somewhat”.

The most recent joint statement by the Quad’s foreign ministers was released in February.

In it, Asean centrality was “right up at the top”, pointed out Gregory Poling, senior fellow for Southeast Asia and director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the CSIS.

These are engagement efforts taking place in a region that is “much more heterogeneous than NATO”, noted Nagy.

“(NATO countries) have the same political systems … similar economic standards, and they’re well integrated into each other’s economies, whereas (in) Southeast Asia and Japan and Korea, we have a variety of government styles,” he said.

“We have a variety of commitments to democracy, a variety of development levels.”

Hence, on the question of the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy, he thinks it “doesn’t make sense” to equate NATO to the Quad.

WATCH: US-China: Is a new NATO emerging in Asia? (46:57)

BILATERAL ALLIANCES

Quite apart from any parallels to NATO, however, developments in the South China Sea may be giving the US’ strategy a boost.

For example, an hour from Singapore, work on a US-funded Indonesian maritime training centre has commenced.

The centre in Batam will be owned and operated by Indonesia’s Maritime Security Agency, or Bakamla, and will aid the agency in overseeing Indonesia’s territorial waters and its exclusive economic zone.

The project is of significance as Bakamla has intensified patrols in recent years to deal with Chinese fishing boats — escorted by Chinese Coastguard — sailing into what Indonesia regards as its territory.

“Indonesia needs to upgrade its Navy and also its maritime capacity. Having defence co-operation is one of the best ways,” said Klaus Heinrich Raditio, the author of Understanding China’s Behaviour in the South China Sea.

“Batam’s location is very strategic … And we’re aware that the US has a lot at stake in defending the freedom of navigation in the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea.”

According to the US State Department, the US provided Indonesia with almost US$39 million in 2020, mostly in security assistance, plus spending on military financing and military education.

In the Philippines, the annual Balikatan exercise between US and Philippine forces concluded last month. It was billed as the largest-ever edition, and in a first, the US’ Patriot missile system was deployed during amphibious operations.

“We can assume that this is part of the different theatre (of operations) scenarios,” said international relations expert Charmaine Misalucha-Willoughby. “This is likely in preparation for China’s next move in Taiwan, or whatever might happen in the South China Sea.”

The associate professor at De La Salle University in Manila also noted that the US is a preferred partner in the Philippines.

She and her colleagues conducted a study of perceptions in the Filipino strategic community in 2020, for example, and the majority preferred to be partners with Australia, Japan and the US — the Philippines’ traditional partners.

“China is way down on the list,” she said.

Especially after Washington was “blindsided” by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-Americanism when he took office, it is likely that the US is now “much more aware” of how strategically important its alliance with the Philippines is, said Poling.

“The Philippines and the US are now beginning to have the kind of conversations that the US has had with Japan, Korea, Australia and NATO for three decades,” he added.

With specific reference to NATO, Article 5 of its treaty states that there are collective defence obligations in the event of an attack on any member.

To bind countries in the Indo-Pacific to a mutual defence treaty, however, “would be a fool’s errand”, said Kuok.

“The US knows that … Southeast Asian countries in particular all have different interests and different positions vis-a-vis China as well as one another. I don’t think that the US is trying to build NATO in Southeast Asia.”

But as the superpower advances its Indo-Pacific strategy, Gao worries that it may lead to not only miscalculation but also “very dangerous courses of action”.

“Now with Ukraine in the middle of this war … we need to realise the value of peace and stability,” he said. “We don’t want to be hijacked by any single big country.”

Kuok, meanwhile, thinks the choice for Southeast Asian countries is “very clear”.

It is not so much as one between the United States or China, but rather “one that supports a rules-based international order and the rule of law, or a world where might becomes right”. “I choose the former,” she said.

“I wouldn’t like to see the world, and particularly not the region, descending into a situation where might is right. And we’ve seen what happens in a scenario such as that: In the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

Watch this episode of When Titans Clash here.