Can online technologies save youths from suicide? There are solutions, but hurdles too

Is it possible to identify youths searching for suicide-related content online, push support services to them and alert their parents — all at the same time? The programme Talking Point investigates.

Enacted photo of a youngster searching for suicide information online.

SINGAPORE: He was a playful youngster who loved films and bowling. But in February 2018, after a difficult year that left him feeling overwhelmed, Josh Isaac Ng tried to kill himself.

Doctors managed to save the depressed 20-year-old. That was when he confessed to his mother that he had been googling for ways to end his life — and he had found instructions online on how to do it.

From then on, Jenny Teo monitored her only child round the clock. “I literally practised surveillance, diligence, watching him very closely, physically day and night, to make sure that he was physically safe,” recounted the 60-year-old.

She was also angry that there were online guides to suicide. “This information shouldn’t be available to our young people. It can really influence the mind of a suicidal person to make a decision,” she said.

“(With) what he did on social media and all that, it was very, very difficult for me. Because there’s no way to physically monitor 24/7. It’s impossible.”

Four months after Josh’s first suicide attempt, she found him dead in their home.

Last year, Singapore lost three times more youths to suicide than to transport accidents. There were 94 suicide deaths among those aged 10 to 29, the same tally in 2018 for this age group.

READ: Number of suicides among those in their 20s highest in Singapore

READ: Authorities keep ‘close watch’ on suicide rates as experts lay out risk factors for young adults

And research has shown that individuals use the Internet to search for suicide-related information. While the causal link between such Internet use and suicidal behaviours is unclear, Teo thinks technology companies “probably can do more” to mitigate the risk.

She cited an example last year: A 16-year-old girl in Sarawak asked on Instagram whether she should choose life or death — and 69 per cent voted for death. Hours after the teenager had posted the poll, she was found dead.

“The response literally made her do it. I wish that the tech companies would’ve alerted the parents of this girl,” said Teo, one of four mothers who started the PleaseStay Movement to prevent youth suicide.

Can technology help to save these youngsters? Taking up the question, the programme Talking Point goes in search of solutions, and identifies obstacles in the way.

WHAT BIG TECH IS DOING

Worldwide, a life is lost to suicide every 40 seconds, reports the World Health Organisation.

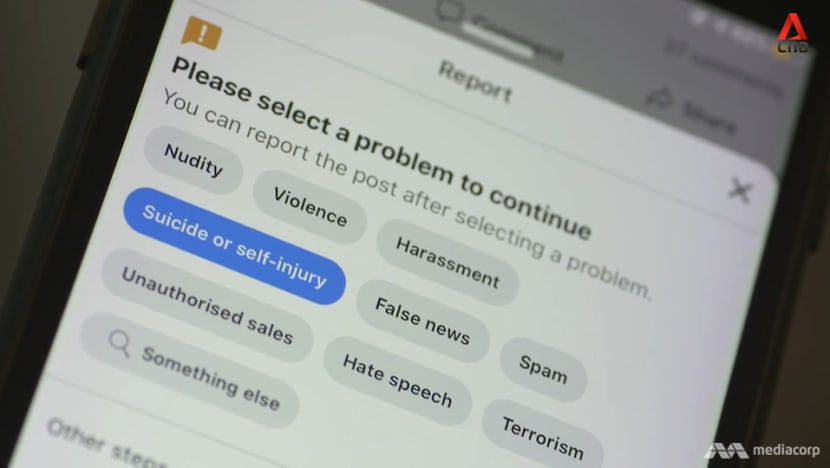

It is a statistic Facebook has highlighted too, which is why its users can report any post or video that may indicate suicidal intent. According to protocol, the company will push support options to the person at risk.

Besides alerts from its community of users, Facebook depends on its artificial intelligence algorithm to pick out words or images that may signal self-harm.

In reply to queries, the company said it would alert the Singapore Police Force when it has “a good-faith belief that sharing the information is necessary to prevent death or imminent bodily harm”.

Posts are also removed. Between last July and this June, Facebook took down almost 10 million posts, including content that violated the platform’s policies on suicide and self-injury, before users even alerted the company.

On Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, suicide and self-injury content has been made “harder to find”.

“We’re applying sensitivity screens to all suicide, self-harm and eating disorder content that’s been reported to us and doesn’t violate our guidelines,” the company also stated. And it is “directing more people” to organisational support.

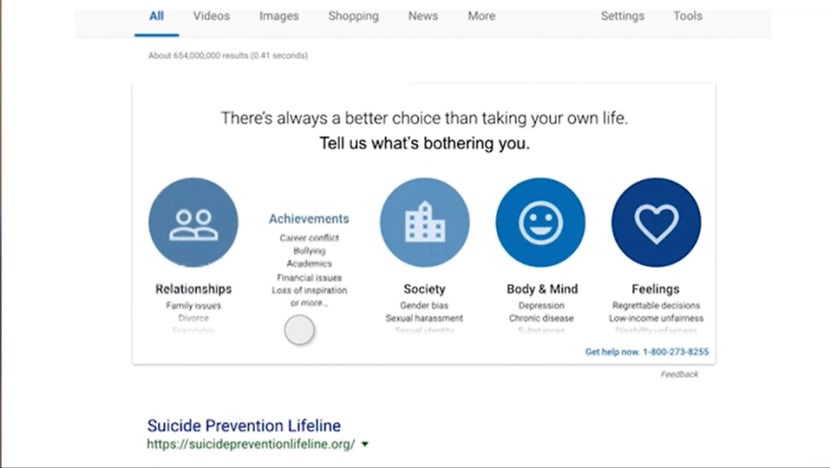

Search engines can also play a part in averting suicides, more than they are currently doing, thinks Lucas Chae, a user experience designer in South Korea.

One time at university, “stressed out from all the workload” on a day that was “just a little too demanding”, he made a suicide-related search online on the spur of the moment.

The message he got at the top of the search results page was: “You’re not alone. Confidential help is available for free”, along with a crisis management helpline number. He felt the response was impersonal.

“I can’t even begin to imagine how it would feel to people who are actually on the verge of committing suicide,” he said. “It’s going to be a very ineffective way to change their minds.”

He found out that the click rate for the top suicide prevention link presented in search results was about 6 per cent, which spurred him to come up with an alternative interface in response to searches suggesting suicidal intent.

His design asks users what is bothering them, and they can choose between relationships, achievements, society, body and mind, and feelings. “Any user can relate to at least one of the five categories,” he said.

Users would finally be prompted to click on a page with a “motivational or helpful” quote and a “lived experience of someone who went through something similar”.

“And then a resource or support system that they can directly reach out to,” Chae added.

With suicide the leading cause of death among those aged 10 to 29, this is why he thinks user engagement is important. “These are the people who have grown up (with) the Internet,” he said.

“When they have problems, they go online to find answers … Having a display that shows there are people who care out there online (would) be the most accessible way to reach out to people who need the help.”

AN APP TO FORGE CONNECTIONS

Chae’s interface still relies on youngsters reaching out for help when their suicidal thoughts are detected. There are apps, however, that have the potential to be early prevention tools for people in distress.

READ: The challenges young people face in seeking mental health help

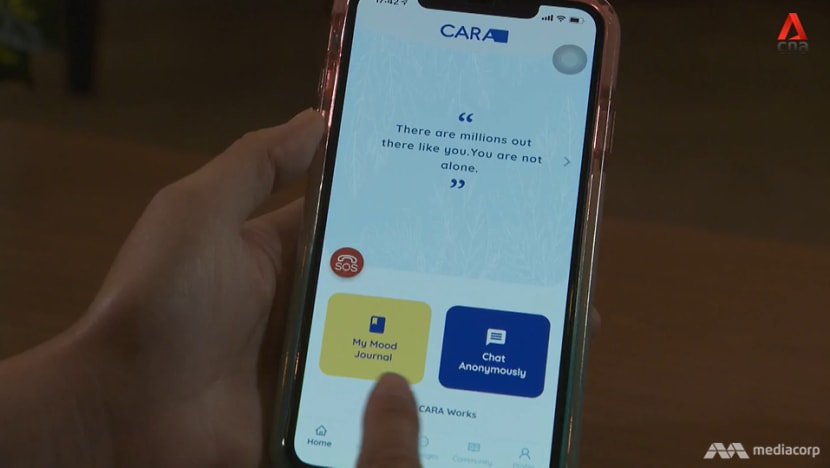

CARA Unmask, for example, is targeted at individuals who struggle with mental health and is a platform that connects them to peer and counselling support as a first step towards mental wellness.

Users can select a trained volunteer with whom they feel comfortable having a text chat. They can also turn to a list of therapists for professional help.

“Most of our volunteers, or CARA Friends, are people who’ve been through mental health issues before. So they can share lived experiences,” said co-founder Orapan Hongchintakul.

Mental health advocate Sabrina Ooi, who helped Talking Point to assess the locally developed app, thought it would be useful for when an individual wants “someone to talk to”, for example.

“There are also other features, like the journal and the community. So it helps to be an outlet for my own thoughts,” said the 29-year-old, who had experienced bouts of major depression from 2013 and attempted suicide in 2016.

Although the app is not designed to be a crisis management platform, its algorithm can detect keywords that suggest a suicide risk when the user is chatting.

CARA Unmask then triggers an alert that enables the user to call the Samaritans of Singapore. The volunteers can also intervene if they feel that they cannot “de-escalate the situation”.

“We can retrieve the user’s IP address and notify the authority. And for users who registered their details, we do ask for emergency contacts whom we can reach out to,” said Orapan.

One of the things the app needs, however, is to pick up the new vocabulary youths are using to “communicate that they’re going through negative thoughts”, pointed out Ooi.

“For example, on TikTok … youths are sharing their favourite pasta recipe and even talking about shampoo and conditioner. They’ve actually been saying all these things to communicate how they themselves feel suicidal,” she said.

For the keyword crawler and algorithm to keep up with these trends, the app needs “a bit more users and a lot more conversations to happen”, acknowledged Orapan, so that its team of creators can “learn more”.

The app was launched about two months ago and does not have many users yet, she added. This may also be why the team has not yet had to notify the authorities of any imminent emergency.

WATCH: Can technology save our children from self-harm? (22:55)

There are other limitations too: CARA Unmask works only if those at risk download it and share their feelings on the app; and users must be 17 years old and above.

PARENTAL TOOLS AND THE NEED FOR BUY-IN

For Talking Point host Diana Ser, whose children are younger, she “certainly would like to know” if they display any suicidal behaviour online. “That’s why it’s crucial that a parental monitoring tool is available in Singapore,” she said.

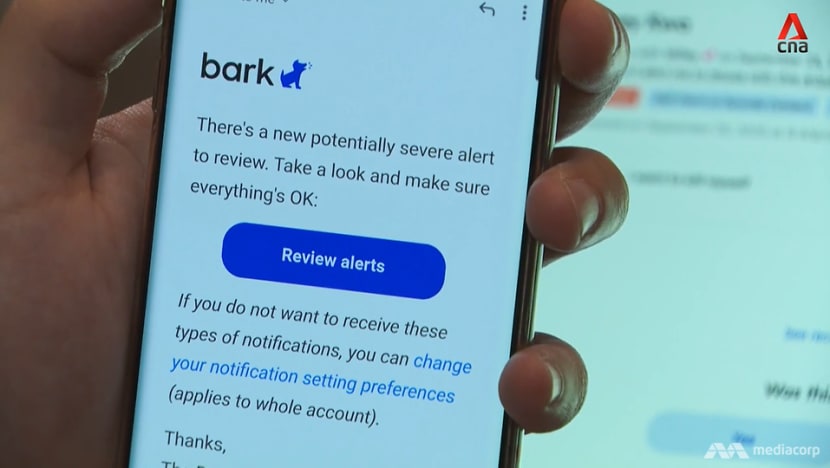

With help from Lester Law, the founder of app developer Sleek Digital, she found out that there are many parental monitoring apps. But only one, called Bark, can send automatic alerts to parents when its algorithms detect suicidal thoughts.

It tracks interactions, including text messaging and email, on more than 30 apps and social media platforms, and has detected 75,000 “severe self-harm situations”. But it is available only in the United States.

Law was able to code a “simple app” similar to Bark, however, to demonstrate how parental notifications can be sent if children use suicidal search terms on their phones with the app installed. Detecting these keywords was “the easy part”.

“The biggest challenge is to reach out to multinational companies — like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat — and get their data on our third-party app,” he said.

It would take “probably six to 12 months” to develop an app like Bark. “But at the same time, I can’t guarantee that we can build it unless we have the approval from all these different platforms,” he added.

When it comes to getting buy-in in the mental health landscape, big tech companies are not the only challenge, as Orapan found out.

While she managed to update CARA Unmask over a two-week period with the help of Ooi, who had suggested improvements to its navigation and emergency pop-up, she had difficulty ramping up downloads because organisations were not that forthcoming.

“We emailed a few potential partners, for example an organisation that provides peer listening services and therapists for youths. It hasn’t progressed very far,” she said.

“We’re quite new in the market, and we need to get more understanding in terms of how the app could supplement their services. So we’re keeping the conversation open.”

Ooi, a co-founder of Calm Collective Asia, a community for good mental health, thinks organisations are also “wary” of giving focus to youth suicide “because it’s still a very thorny issue in our society”.

But this is precisely where Orapan thinks technology comes in.

“We believe in our hearts that if more people use apps like ours and other mental health apps, the more data we can gather, the more we learn about our users and the more we can do to prevent suicide,” she said.

Ooi agreed that “it’ll be able to help youth manage their mental health”. But at the same time, “when you talk about youth suicide, it’s really about being able to normalise the conversation around suicide and mental health”, she added.

Having previously googled “many times” about committing suicide, her message to struggling youths is this: “Don’t be afraid to ask for help, whether it’s from your family, from your friends or online. There are a lot of support groups out there that can help you.”

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. New episodes on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.

If you need help, call:

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444

Institute of Mental Health helpline: 6389-2222

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

Care Corner Counselling Centre (Mandarin): 1800-353-5800

Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788

Silver Ribbon: 6386-1928