Deepfakes, nudes and the threat to national security

While it seems like a bit of entertaining video wizardry, deepfakes can make people say things they never did in real life and influence public opinion. And the technology has got some people scared.

One of these images is a deepfake. Can you tell which? (Answer: On the left.) (Screengrab: CNA video).

SINGAPORE: It looked, and sounded, like United States President Donald Trump taunting Belgian citizens about climate change.

“As you know, I had the balls to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. And so should you,” he said, looking at the camera. “Because what you guys are doing right now in Belgium is actually worse.”

It provoked hundreds of comments in the first few days from angry Belgians directing their fury at Trump.

But that video last year was fake, created with “deepfake” technology by a Belgian political party that was out to redirect people to a petition calling on the Belgian parliament to take more urgent climate action.

Deepfakes are created using artificial intelligence whereby an existing image is replaced with someone else’s likeness — a manipulated video.

While it seems like a bit of entertaining video wizardry, these forgeries can make people say things they never did in real life, influence public opinion or even affect elections.

And in a climate where misinformation feels rampant, this new technology has got some people scared, as the programme Why It Matters discovers. (Watch this episode here.)

IT CAN BREED DISTRUST

A recent study has shown that the number of deepfake videos almost doubled in nine months. Cybersecurity firm Deeptrace found 14,698 deepfake videos online in September, compared with 7,964 last December.

Deepfakes “play a dangerous game with transparency, authenticity and trust”, creative agency We Are Social says on its website, and the real danger “lies in spreading fake news”.

READ: China seeks to root out fake news and deepfakes with new online content rules

Some states, for example, use deepfake technology to disrupt a target, points out S Rajaratnam School of International Studies senior fellow Benjamin Ang.

WATCH: How to spot a deep fake (3:22)

“They won’t just put fakes on one side of the political story. They’ll put (fakes) on the other side as well,” he says, citing research done on national security issues.

This breeds distrust among the people, and in a worst-case scenario, “anger could escalate into violence, which then creates even more distrust”.

But even when a deepfake is identified as such, why do people get fooled by it?

Lim Sun Sun, head of humanities, arts and social sciences at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, explains that this is confirmation bias: The tendency to favour information and views consistent with one’s pre-existing beliefs about individuals or issues.

The fake Trump video is a successful example of social engineering, she says, because it “taps into the belief that people have about (him) being a climate change denier”.

She adds: “State-funded misinformation to advise (on) a certain position … is an age-old problem”.

For example, during the Japanese Occupation in Singapore, there were staged photographs — published in magazines — of the Japanese doing healthcare work, helping the sick and giving out rations.

“It’s a form of propaganda in the sense that the Japanese Occupation government was trying to ... give the impression that they were doing a very good job of running Singapore,” says the professor.

IT CAN REMOVE CLOTHES

Nowadays, as deepfake technology becomes more accessible, it is being used not only against politicians and public figures, but also to target women.

Arnaud Robin, We Are Social’s director of innovation for Singapore, notes that 96 per cent of the deepfake videos online are pornographic. “The faces of celebrities (are pasted) on porn videos,” he points out.

The earliest application of deepfake technology allowed for face swaps only. But developers, some anonymous, have since come up with apps such as DeepNude, which can remove clothes from women in photos for a small fee.

While it shows inconsistent results, mostly failing with poorly lit or low-resolution photographs, it can be convincing if fed the right images.

Take, for example, the bikini shots and alluring poses of teen model Naomi Huth on Instagram, where she has almost 10,000 followers, mostly men. Her kind of high-resolution photos work best for an app like DeepNude.

She thought nothing of her posts, however, until she learned about the dangers of deepfake from Why It Matters host Joshua Lim.

“If this technology would be run on me, I’d feel very violated,” she says. “A lot of people who wouldn’t know me would probably believe (what they see). And that’s the scary part.”

If such deepfakes were to be shown all over social media, “that can destroy people’s lives”, adds the 19-year-old, who got “goosebumps” finding out that there are deepfake videos too.

That’s how scary that is because people will never know if it’s you any more.

FIGHTING BACK

To combat deepfakes, Silicon Valley's tech companies and social networks are building tools like Google’s open-source database containing over 3,000 manipulated videos. It was released in September to help researchers better identify and take down deepfakes.

Start-ups like Dessa are also working on detection tools, while Twitter is ironing out new rules to protect users from deepfakes.

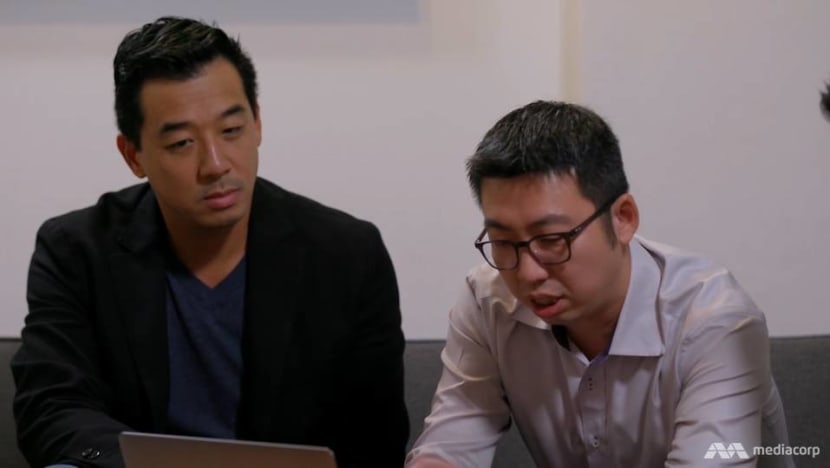

In Singapore, local company Black Dot Research was set up last year to fact-check stories that are shared on social media without a second thought.

Its founder Nicholas Fang says that while it is not hard to dispute and debunk a fake video of an actual person, it is a problem when there is insufficient time to do so.

On Polling Day, for example, a deepfake video could emerge, in which “one of the critical personalities” from one of the parties says something.

“People have a couple of minutes to process this before they go and vote,” he cites. “That could be enough to tip certain people’s opinions over.”

His colleague Derek Low thinks nothing beats the public “having a good, strong gut instinct” for questioning whether something is real.

But there is also a flip side that worries Lim. “We already take what we receive and circulate on the Internet with a pinch of salt,” he says.

“So deepfakes feel like yet another reason to dismiss what we see online. But that’s where the true danger lies, because in doing so, we might just, accidentally, dismiss the truth.”

Watch the episode here. Why It Matters is telecast every Monday at 9pm.