Life on the outside, after 35 years in a mental ward

Committed to the IMH for schizophrenia, Sim Kah Lim receives an unexpected discharge thanks to his sister and his art — of which he's holding an exhibition today (Nov 16).

SINGAPORE: Like clockwork, he is up by 7am daily and spends most of his day in his sister’s flat, catching up on his Channel 8 dramas, reading or writing his diary.

It sounds like a mundane life, but these are the best of times for a man who, for 35 years, had only known the routine of life behind the walls of a mental institution.

Until recently, you see, Sim Kah Lim was one of the longest-staying patients in the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) — those who have been warded for more than a year, where all possible discharge options have been explored and had failed.

There are now about 1,000 long-stay patients, who mostly have major mental health conditions “that interfere with their ability to lead independent lives or integrate well into the community”, said the IMH’s advanced practice nurse, Goh Ai Sze.

Kah Lim, however, received an unexpected reprieve and was partially discharged late last year — free to return to the world he left behind in 1983.

He was 15 years old when he was institutionalised for schizophrenia.

“Got freedom, very happy … Like a pigeon, I can fly away,” he mumbled with a grin to CNA Insider.

“I take my bag. I can bring it all around Singapore to go and paint, like (the painter) Vincent van Gogh.”

The 51-year-old is something of an anomaly now, as it is not common for long-stay patients to be discharged.

Said younger sister Cindy Sim: “The day when (the IMH) told me that he could go out, I was very happy for him because he wanted this to happen for many years.”

ROAD TO RECOVERY

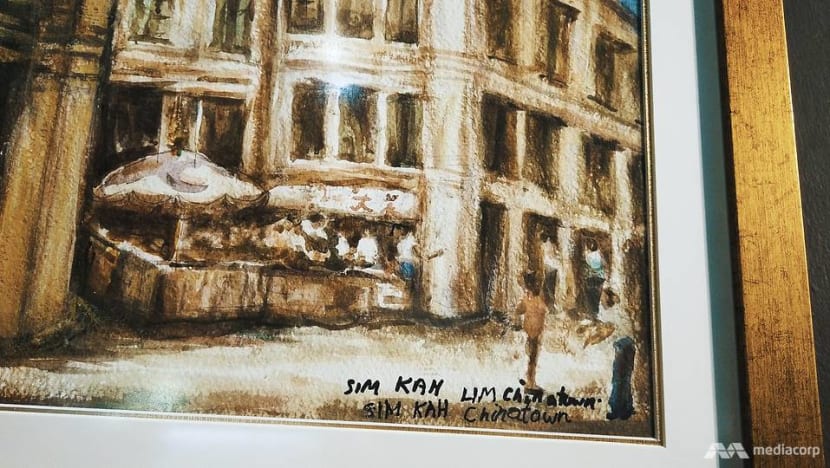

From young, Kah Lim had loved painting, and his father used to take him to the Singapore River and Kampong Glam to paint and learn from the artists who gathered there.

His behaviour started to change, however, when he became a teenager. He started talking to himself and refused to leave home.

He was subsequently admitted to the IMH, but he never stopped painting even behind the confines of its walls.

READ: In a mental ward for nearly 35 years, he paints old Singapore from memory - and he dreams

His sister understood the importance of family support and made sure that she remained a constant in his life. She even moved to Hougang, to be nearer to the IMH so that she could visit him regularly.

“Family members play a big role in a patient’s recovery,” she said, adding that she visited him almost weekly over the 35 years, unless she had to travel for work.

“Everybody needs family to visit them. They want to talk about their daily life … (and) about the old days.”

He would constantly reminisce to her about his childhood. “Family members are the ones who bring back their memory and help them to think, ‘I still have a sister, a brother, a father, a mother,’" she said.

Mental health patients do need family support to experience kinship, bonding and to help them towards recovery, said Dr Lim Boon Leng, a psychiatrist at Gleneagles Medical Centre.

Cindy also thinks her brother’s recovery was partly thanks to his dream of showcasing his art coming true.

In July last year, some of his works were selected for an exhibition highlighting the importance of mental health. Two months later, he held his own exhibition, organised by Goshen Art Gallery.

That people appreciated and bought his paintings helped him to regain his confidence, said Cindy.

READ: Flood of interested art buyers, and a job offer, for artist living in IMH

READ: A dream unfolds for artist living in IMH, with a special exhibition and meeting

“Since young, he'd wanted to show his art to many people. But his dream wasn’t fulfilled for so many years, so his condition also didn’t really improve,” she added.

Goshen co-founder Faith Lum-Yu had hoped his solo exhibition would help him reintegrate into society. And during the event, she saw how excited he was — talking to people, shaking their hands and taking selfies with them.

“It means a lot to him that people admire his work and ask questions about it,” she said. “We could see the change in him as well. He was definitely connecting with people more.”

When Cindy noticed the changes in her brother, she explored with the IMH the possibility of his release.

“When he got his art exhibition, he felt good — he felt that he was useful. That’s how he got his confidence back,” she said.

“To him, everything is about art. When his art is appreciated … he doesn’t think about other things, like his unhappiness.”

In fact, Kah Lim is holding another exhibition at Goshen from today (Nov 16).

PERIOD OF ADJUSTMENT

But before a patient can be discharged, a multidisciplinary team from the IMH must assess his or her mental health condition and rehabilitation potential.

They draw up rehabilitation goals and care plans, including teaching the patient about independent living and vocational skills such as money management.

“It’s not easy for them, as society has changed so quickly. A lot of things were previously done for them (in the ward),” said Lim.

“They have to take care of themselves and get used to a new environment and technology. When staying with family, it’s unavoidable that there’ll be conflict.”

Cindy admitted that her family had to make some adjustments, as they were not used to having Kah Lim around. He sleeps in the living room, so that they can keep an eye on him.

“His behaviour is a bit different — he likes to sing. At home, we’re always very quiet, except for the dogs,” she said.

“We told him not to make so much noise. He’s very co-operative and knows he isn’t allowed to sing so loud.”

What he has struggled with is money. Cindy once gave him S$100, as he wanted to “feel rich”, but he blew it all in one day on his meals, chocolates and shampoo for the family.

He now gets between S$5 and S$10 daily pocket money, enough for some of his meals outside.

WATCH: Life on the outside, after 35 years in a mental institution (4:41)

He once even snuck out for supper at midnight and got lost. It was only in the morning when he was discovered missing.

Thankfully, a Grab driver called to say he had found Kah Lim in the Upper Serangoon area, about 20 bus stops away from home. Cindy now keeps the house keys at night.

These days, her brother is home for about three weeks each time and returns to the IMH for about a week.

“I don’t want him to have hopes (of) … doing anything he wishes. I’m afraid he may relapse,” she said. “I’ve seen some cases where, after years of integration, they relapse.”

A businesswoman, she usually schedules her overseas work trips when he is back in the IMH.

Meanwhile, he makes it a point to buy snacks for his friends inside when he returns. “Once in a while, (I) must go back, (for a) change in environment and (to) see friends,” he said.

THE CHANGING TIMES

Community support is also important for mental health patients who are trying to reintegrate. The IMH said its multidisciplinary team works with family members to support patients, and links them up with the relevant community resources.

Cindy is heartened, for example, to have a nurse call her every night to check on her brother.

In the past, Lim noted, even when institutionalisation was not necessary, “there weren’t enough services in the community to support (people with mental illness)”.

“Family members may not have been familiar with that (illness). If a person was noisy, for example, the neighbours may have discriminated,” he said.

“Now we have much better community services to help this group, and that allows them to go back home.”

Medication for schizophrenic patients also has fewer side effects these days, which “makes it easier for them to integrate back into society”, he added. But they must take their medication, else they may suffer a relapse.

According to the IMH, relapses can happen also because of work and relationship stress, poor coping mechanisms and the inability to adjust to community living. In such cases, the patient may have to be re-admitted.

When he first moved back, Kah Lim’s relatives got him acquainted with the neighbours and shop owners.

(My neighbours) don’t feel that (having) Kah Lim around is strange … They accept him for who he is.

"He’s not the only one with such a condition,” added Cindy.

He has become familiar with the area, and walks alone to a nearby coffee shop for his char kway teow, char siu rice or nasi lemak almost every day.

And since leaving the IMH, he has put on 12kg, his sister complained. “He’s been eating a lot — (in) one day, at least four (or) five meals,” she said. “In his mind is either painting or food.”

To which Kah Lim gave a practical reply: “If you don’t eat now, (when you) die already, (you) cannot eat.”

He does help with the housework, walks the dogs and runs errands for the family, such as buying groceries from the wet market.

Engaging patients with schizophrenia to run errands or do chores helps to improve their confidence and their mental functioning, said Lim.

“They tend not to do much at home,” he added. “They don’t talk much, and given the choice, they’d sit in a corner and not do anything.”

MORE TO LEARN

Kah Lim, however, paints as much as he can. Every Sunday morning, he heads to eminent artist Choo Keng Kwang’s house to be mentored.

Choo used to give him painting tips by the Singapore River when he was a boy, and the two reconnected last year after Kah Lim started exhibiting his work.

“The two men like to talk about art,” said Cindy. "They enjoy each other’s company. Both of them talk about how to improve Kah Lim’s painting."

Going forward, she wants him to learn more, like how to take public transport to her nearby office.

She appreciates that she has more time with her brother these days; she chats to him every morning before work and makes it a point to be home early in the evening.

She thinks that for some mental health patients, giving them a chance to return home may be helpful. But she acknowledged that not all families would be able to arrange for that owing to work commitments or old age.

“That’s why I don’t want to do it (bring him home) when I’m older. I want him to learn to live by himself in case I can’t take care of him,” she said.

“At least he’s experienced life outside, rather than inside the hospital his whole life. He’s already stayed there for 35 years.”