Can a millennial hawker rejuvenate her great-grandfather’s zi char stall?

Fourth-generation hawker Debbie Yam uses social media marketing and tweaks classic dishes to help her family’s 74-year-old food business. But the passing of the baton comes with reservations, the programme Belly of a Nation finds out.

Debbie Yam, 30, has a few ideas about how to take her family’s legacy to the next level.

SINGAPORE: When aspiring hawker Debbie Yam started working at her family's zi char stall, she was forbidden from cooking for customers after she burnt even simple dishes, like fried rice and hor fun.

Tang Kay Kee Fish Head Bee Hoon was a household name serving traditional Cantonese-style fare, and Yam was a business graduate who ended up being relegated to basic kitchen work, such as cutting up vegetables and seasoning the food.

“For hor fun or fried rice, you need to have wok hei (wok ‘breath’ in Cantonese). Mine was just black,” she recalled.

“In the beginning, when I was learning how to cook, I burnt a lot of my hair, my eyebrows and a lot of food. My friends who came to support me had to eat my burnt food.”

Only after months of training did the matriarch of the family business, great-aunt Tang Yock Cheng, allow her to serve customers a dish of fish head bee hoon that she cooked herself.

It was the same for her undergraduate cousin, Kamen Tang, who worked there at weekends and over the school holidays.

“She made us first cook for ourselves to eat and then for her to eat, and then for our friends,” said Yam. “So by the time we could serve customers, it’s been fine-tuned to perfection, according to her.”

The 30-year-old is among a small number of young hawkers answering the call to carry on the trade. And she has a few ideas about how to take her family’s legacy to the next level.

But even as a new generation has hopes of transforming the business to appeal to new customers, the current generation has certain reservations due to old practices, the programme Belly Of A Nation finds out.

WATCH: Singapore hawkers and those keeping the trade alive (47:31)

STALL WAS NEARLY SOLD

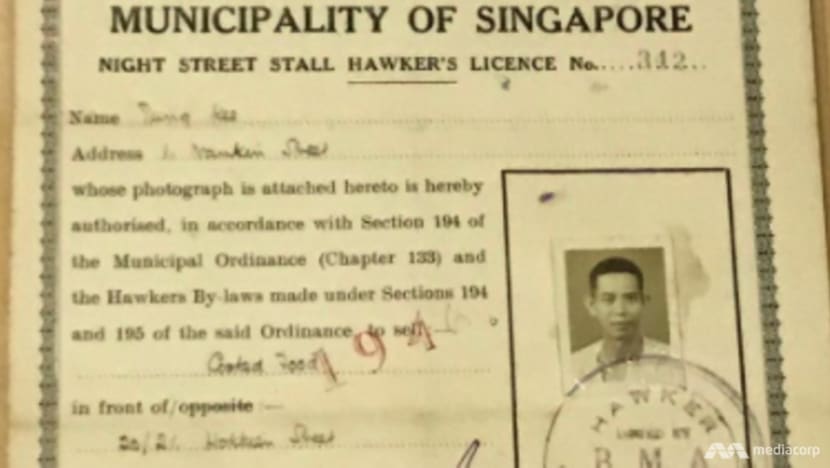

Tang Kay Kee Fish Head Bee Hoon was started in 1946 by Yam’s great-grandfather Tang Pak Kay, a pushcart vendor who peddled his food along Upper Hokkien Street in Chinatown. And he had a little peculiarity — he went around barefoot.

“At that time, a pair of wooden clogs cost 70 cents … But he wasn’t willing to buy them,” great-aunt Tang said in Cantonese. “He was stingy. He wanted to save money because he had a family.”

After he died from old age in the 1970s, she took over his stall, which was then moved to Hong Lim Market and Food Centre in 1978 when the authorities resettled street hawkers in purpose-built hawker centres across the island.

“She took over because she was the only one in the family who wasn’t married,” said Yam. “She was the one with the most time and had no commitments.”

Great-aunt Tang was afraid, however, that the business would suffer after the resettlement.

Previously when she was selling food from the pushcart, many customers who drove used to wait along the road to pick up their orders.

“She was worried that no one would park their car and buy from her at the hawker centre,” said Yam.

Unsure about how business would pan out, she did not even buy a fridge for the stall, opting instead to carry foodstuffs from her nearby flat to the stall every day.

But business improved, so she bought one a few months later.

Yam remembered hanging out at the stall at weekends as a child, helping to wash the dishes. “We’re a very tight-knit family. Our relatives used to help her at the stall — including my parents,” she said.

In 2016, however, her great-aunt wanted to sell the stall owing to a manpower shortage. Yam, who was in New Zealand in a holiday job, got wind of it and told her to hold off the sale until she returned.

“Her whole life was dedicated to this stall. If there’s no hawker life, her life would be quite meaningless,” she said.

In addition, Yam — who has a management degree from the Singapore Institute of Management Global Education in association with the University of Manchester — did not mind being a hawker.

“I want to learn things. I think it’s a very interesting trade, and I see an opportunity to … gain (some) experience,” she said.

RESISTING CHANGE

Yam’s parents, who are in the construction business, supported her decision but warned her of the long hours and physical demands ahead.

But what she did not expect when she started working there in 2017 was that her great-aunt, who is now 75, and the older workers at the stall would be so resistant to change.

For example, she wanted to introduce plastic takeaway containers, but Tang refused and said it was an additional cost for customers.

“(The older folks) have been doing things their way for so long. They don’t want to change anything, even small things like that,” said Yam.

“They want to keep using paper boxes. But it’s a waste of time folding (these), and we have a manpower crunch.”

When she proposed a lunch service, Tang had her doubts. The stall had never opened that early, as the crowd from the Central Business District seemed strapped for time.

“In the daytime, no one ate zi char because my father took a long time to cook fish head bee hoon,” said Tang.

“For one bowl, he’d take at least 20 minutes. He wanted to cook it till the soup was beautiful.”

Yam managed to convince her great-aunt, however, to let her sell two dishes — fried rice and hor fun — starting in 2018.

“There’d be no loss opening the stall during lunchtime,” she reasoned. “Rental is a fixed cost, and there’s no added labour cost, as I was the one cooking.”

At first, the stall struggled to draw the crowd. But in true millennial style, she turned to social media to market the lunch menu.

“We put up posters and Instagram-worthy photos. That helped to capture people’s attention,” said Yam, who had experience doing social media marketing while working at a cafe previously.

When business picked up, she wanted to revamp the lunch menu with a zi char concept inspired by poke bowls.

Again her great-aunt was sceptical, commenting that those dishes — such as spicy braised pork belly rice and hor fun with sous vide egg — were “nothing special” and would not sell.

“When I tried to introduce different bowls, (the older workers) resisted it and wanted only the traditional flavours,” said Yam. “I’m from the younger generation; I’d know what’s popular with the younger crowd.”

Sure enough, these lunch bowls became a hit, filling a lunch vacuum the business had for decades. However, Tang did not let her introduce the concept for dinner.

“She said that it isn’t going to sell. She still prefers to sell family-style zi char dishes at night,” said Yam.

Another of her suggestions was a point-of-sale (POS) system to make the ordering process more efficient. “(When) one order comes in, they have to shout (the order) at least three or four times to each other,” she said.

“They’re a bit old, their hearing may not be the best, so it gets confusing.”

Tang, however, said no. She was afraid that someone would steal the POS terminal and make off with the takings.

FEELING BURNT OUT

Two years ago, Yam — who was living with her parents in Choa Chu Kang — moved into Tang’s flat in Chinatown to spend more time with her great-aunt and do away with commuting.

“The (working) hours are excruciating. It’s hard for a young-generation hawker. I see my friends going out for dinners and parties, and I can’t join them … I’m leading a different lifestyle,” she added. “And I really miss smelling nice.”

Her toughest period as a hawker was when COVID-19 hit, especially during the “circuit breaker”. She introduced a delivery service to address the drop in customers, and the first week was the hardest on her.

Apart from cooking, she had to manage the delivery orders, the routes and the drivers. “I slept less than two hours every single day because there was a lot of co-ordinating,” she recounted.

“I was very, very burnt out. I remember I broke down at the end of that week. I was like, ‘Oh no, this is only the first week.’ And then at that point, the circuit breaker was two months.”

Her 23-year-old cousin then pitched in to help co-ordinate the deliveries, for example, as she realised she “couldn’t do everything”.

While the pandemic has forced hawkers like her to adapt quickly, the biggest driving force behind the stall, her great-aunt, is not about to change the old ways.

“She’s still going on strong in (terms of) making decisions,” said Yam. “This is her stall — she’s still in charge. If she wants to do it her way, I’ll support her because I’m here (in) a support role.”

Watch the programme Belly Of A Nation here. And read about the 91-year-old hawker behind a historic wonton noodle stall who called it quits.