commentary Commentary

Commentary: The 2010s – when tolerance and pluralism came under attack

With the mass base of intolerance rising globally, Singapore needs to prepare to attempt to ride out some of what is coming, says Shashi Jayakumar.

People watch artists performing at an event to register their concern against hate and intolerance, at a public park in New Delhi, India. (Photo: REUTERS/Anushree Fadnavis)

SINGAPORE: When I squint back at these last 10 years and think about what it will be remembered for, what comes to mind is the opening lines of W H Auden’s poem September 1, 1939, penned at a dismal time - the German invasion of Poland which marked the start of the Second World War:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Auden saw a decade of lost opportunities, freedom and democracy increasingly losing ground to narrow ethno-nationalisms; people roused by demagogues, and impelled to violence by ideology and political lies.

I wonder whether future generations will look back at the challenges of the 2010s and say the same things.

TERRORISM CIRCUIT CHANGING

The terrorism “circuit” – the space where academics, experts and practitioners commingle - is changing as attention spans, including of those who fund such work, are getting shorter.

Even though the Islamic State (IS) is not beaten in the battlefield of the mind, still studying it, and terrorism in general, is important. But there is the feeling, among those of us in the field of security studies, that we can move on and address seemingly more pressing issues like cybersecurity or disinformation.

This is reminiscent of the myopia we had in 2011. Recall the triumphalism we had following Osama Bin Laden’s killing and the concomitant sense that al-Qaeda was a spent force.

READ: Commentary: The end of the decade – how the world has become a less safe place

Instead, we should be using this time to build deeper understandings of all sorts of violent extremism and its feedstock, intolerance.

I tell my own analysts who study radicalisation we cannot carry on as before. We have to understand society, ethnographic approaches, issues concerning tolerance and dialogue. And then maybe we might have something useful to say when IS 2.0 or new forms of radicalism come along, as they inevitably will.

THE MOOD MUSIC

The decade has seen in various places the nostalgic longing to recapture the (largely chimerical) old days and to restore the “pure” (usually monocultural) nation or a pure ideal. The growing narrative of the Great Replacement being propagated by right-wing groups in parts of Europe of that the indigenous white Christian population is being replaced by immigrants abets this.

This is not something that exists simply at ground-level. People are egged on by leaders of different religious and political persuasions.

READ: Commentary: Despite pressures against it, truth survived 2019

This entire mesh becomes part of the mood music, which does not permit space for the other, for someone who looks, acts, thinks or feels differently or who has a different opinion. This is a very monochromatic point of view and is not healthy for pluralist societies.

Individuals whose lives are irradiated by social media – indeed whose validation comes from the interplay of their private and public, social media lives – are alienated from meaning and thereby seek it even more fervently and in different places.

What the French call anomie. Alienation, sense of worthlessness.

Sometimes, this sense of worthlessness can take on a more serious dimension. For example, in the most recent statistics released by the UK Home Office, the largest proportion of referrals in its PREVENT referral programme concerns individuals at risk of radicalisation exhibiting ideologies which are unstable and not altogether clear.

READ: Commentary: Japan’s ageing social recluses need more love and understanding

These individuals depending on what content they find online can shift between different ideologies.

In North America, where right-wing supremacists’ plots and attacks have eclipsed those of jihadist hue for some time, security agencies are now being forced to take niche groups like the Incels (involuntary celibates) movement – part of an online subculture who have been responsible for attacks in North America - as an actual viable threat. Oddball niche threats are metastasising.

READ: Commentary: 2019 was a year of global unrest and rising inequality. 2020 is likely to be worse

Those responsible may be pursuing violence in their search for meaning. But some, from their own point of view, may see themselves as changemakers or activists who have exhausted all other non-violent means to get their point made.

INTOLERANCE

We’ve seen reciprocal radicalisation rear its ugly head in the West. The far right radicals and Islamists feeding off each other in a negative and reinforcing spiral. Egged on by politicians, whose loyalties are to themselves, then to their party, and only then to their country (completely in the wrong order).

We tend to discount this type of thing happening in Singapore because you don’t really have a defined far-right feeding off issues like immigration or asylum seekers.

But the mass base of intolerance across the board is unfortunately rising. You can feel it in the region. We can’t escape this and it comes into Singapore, either through social media, ideas or people.

MOVING UPSTREAM

We need to address the roots of this risky behaviour, some (but not all) of which clearly lies, far upstream, in intolerance.

The decade has seen important upstream work being done internationally – in mentoring people who are lost, who seek direction, but who might one day fall into the “at risk-of-radicalisation” category. Some of the intervention needed for such individuals is not a direct counter-radicalisation one, but more like the social work being done in areas such as prevention for delinquents.

But should we not be going even further upstream?

Preserving common space is going to be critical. In Singapore, we still talk about resilience, understanding, tolerance and multiculturalism without sniggering. There is a diminishing group of nations like this.

Young people in Singapore have of their own accord come together to do this kind of work including the numerous interfaith dialogues and platforms we have.

I have talked to these people – they are committed, they know what is at stake, and they are keen to engage people, away from the crowd of people who usually turn up, in more personal and face-to-face interactions. Efforts such as these are going to be critical in sustaining the bedrock of diversity we have.

(DIS)INFORMATION

George Kennan, the first Director of the US State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, observed: “We have been handicapped however by a popular attachment to the concept of a basic difference between peace and war, by a tendency to view war as a sort of sporting contest outside of all political context."

Kennan wrote this in 1948.

READ: Commentary: Undecided UK voters feel overwhelmed with information

READ: Commentary: Deterrence, retaliation and arms control - a guide to tackling information warfare

When it comes to disinformation and cyberattacks, there are no red lines, with states routinely impugning the sovereignty of others through disinformation and real world interventions.

We need an international treaty that clearly reaffirms what sovereignty means in the information age, but given the lack of international norms, we are not likely to even come close for decades.

In the meantime, the states trying to shore themselves up against these threats will continue to play defence.

Too many studies talk in a general and airy fashion about the panacea. Serious studies are needed to understand what these actually are, how they can be introduced into societies, early, and what real effect they have.

In this respect, funders and policymakers need to understand that not everything that has value can be measured. These things are hard to measure and quite often they slip in between interagency cracks, particularly when no one is looking, or, when we assume someone else is taking ownership.

In other locations, the constant attrition leads to poor political hygiene, enabling all sorts of things – groupthink, demagoguery, the manufacture of outrage, to name some.

The philosopher Sissela Bok, whose life’s work has been the study of lying and deception, observes that lies use deception to narrow our choices in political societies. Lies about politics are therefore, she argues, the “most dangerous body of deceit of all.”

Bok observes differences between states that understand the principles of veracity and honesty and those, on the other hand, that harness the energies of the state to the enterprise of lying. Such societies, she argues - where truth and falsehood are hopelessly jumbled – inevitably implode.

THE SINGAPORE MODEL

Singapore has been spared from a great deal of the world’s vicissitudes. Some people think therefore that it has all the answers. It doesn’t.

Singapore has always thrived in equilibrium and seen the world prosper in such times. How can it counsel otherwise, even if it is targeted, as it increasingly will be, I suspect for failing to take sides?

READ: Commentary: Challenging racism starts in the family

Foreign dignitaries come to us in the wake of domestic events tragedies as they are interested in the “Singapore model” of tolerance.

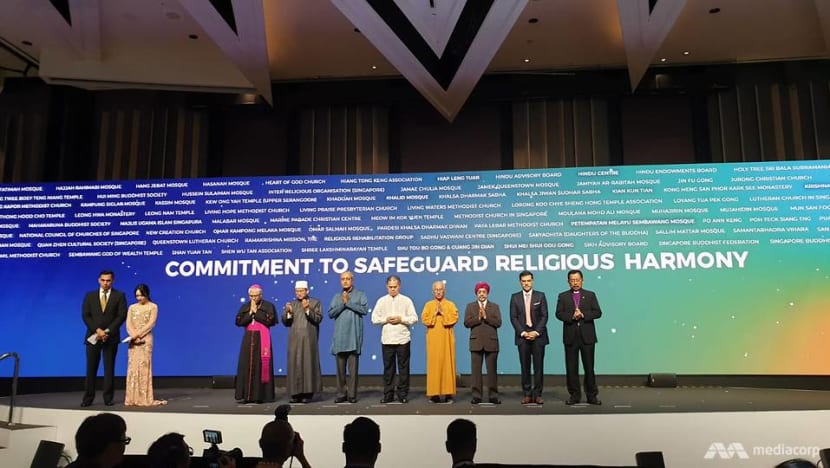

This is why events such as the International Conference on Cohesive Societies (ICCS) organised by the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) with the Ministry of Community, Culture and Youth (MCCY) are going to be very important in time to come – nodes where experts, practitioners, religious leaders and youth ambassadors can come together in an unforced atmosphere, to share notes and experiences.

When the history books are eventually written, if people do indeed look back on this decade like they did the 1930s, I wonder what they will say about states which prized tolerance, veracity and pluralism.

Singapore cannot avoid all of what is coming. But we need to think seriously about building a rugged generation, battening down the hatches, and attempt to ride out some of what is coming.

As our first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, observed in 1965 talking about the Konfrontasi – which was a sort of political warfare mixed with bursts of kinetic action: “We’ve got to build up men and troops who can meet this kind of warfare – you know, constant harassing, constant pressure, no real war as such but international thuggery. This is what it is. And we’ve got to train our men to meet this sort of situation.”

Shashi Jayakumar is the Head of the Centre of Excellence for National Security and Executive Coordinator of Future Issues and Technology at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.