Commentary: 20 years after 9/11, US is finally leaving the Middle East alone

America has lost the will and perhaps the power to achieve reforms needed to stem this form of radical extremism, says a professor.

WASHINGTON DC: It is one of the ironies often played by history that America’s hasty and humiliating exit from Afghanistan occurred on the eve of the 20th anniversary of 9/11.

It was this massive attack on two pillars of American government and society that brought the United States and its armed forces into the country. 20 years, thousands of lives, and trillions of dollars later the Biden administration decided correctly that America’s Afghan venture had to be brought to an end.

The Bush administration’s decision to respond militarily to 9/11 and to destroy Al-Qaeda and its Taliban host was justified and successful. But the decision to stay in Afghanistan and to try to build a functioning local government was America’s first major mistake in formulating its post-9/11 policy.

It is easy to understand the thinking that underlaid the decision to stay in Afghanistan after the initial military success.

Leaving the country to its own devices was likely to end in a return to the status quo ante. But what could and should have been realised in 2002 and 2003 was that the notion of state- and nation-building in Afghanistan by an external power was bound to fail.

BLUNDER OF IRAQ INVASION

The second and greater error was the decision to invade Iraq in 2003. We now know that the claim that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was associated with Al-Qaeda was unfounded. We also know that he had no stockpile of weapons of mass destruction.

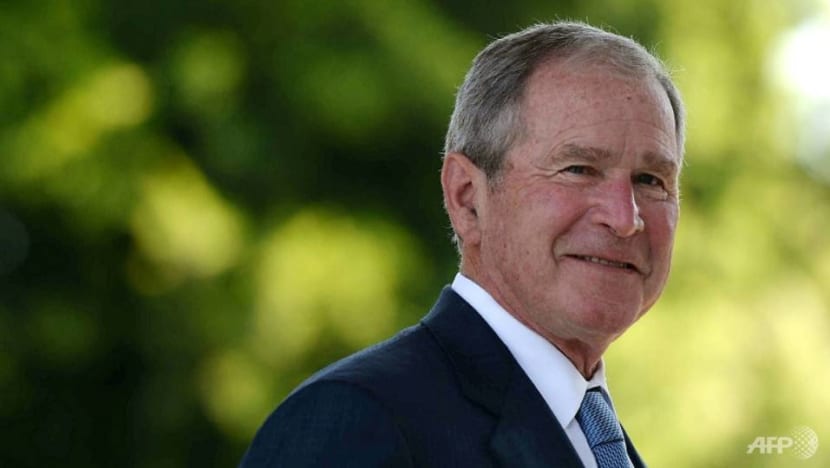

The three principal decisionmakers, President George W Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, were motivated in part by the sense that the military operation in Afghanistan was not a sufficient retaliation for the blow inflicted on the US homeland as well as the expectation that the toppling of Saddam would prompt a wave of positive changes in the Middle East.

We also realise now just how detached from reality the vision of importing democracy to Iraq and from there to other parts of the region was.

We know as well how enormous the cost to both Iraq and the United States would turn out and we are aware that contemporary Iraq is struggling to remain a viable state. The main beneficiary of the Iraqi blunder is Iran.

The Iranians were rid of their nemesis, Saddam, and the road was opened for them to project power and influence into the Levant. Tehran’s quest to build a land bridge to the Mediterranean Sea would not have been feasible without the US invasion of Iraq.

BOOST GIVEN TO EXTREMIST MOVEMENT

A third major outcome of 9/11, the boost given to the jihadi movement, was not a product of American miscalculation.

Al-Qaeda had of course existed prior to September 2001. It had launched effective attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in August 1998 and on the USS Cole in Yemen in October 2000.

The group sought to inflict damage on the hated West and its positions in the Middle East. It also calculated that since it could not accomplish its main aim, toppling the existing regimes and order in the Arab world, it should shift to attacking their major external supporter.

As an act of terrorism, 9/11 was a resounding success. The US responded by decimating Al-Qaeda, but the organisation survived in a weakened form. The Syrian civil war and the weakness of the Iraqi state provided new opportunities.

Three offshoots of Al-Qaeda – Al-Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamic State group, and Jabhat Al Nusra – came to play major roles in the first two decades of the 21st century.

Abu Musab Al Zarqawi’s group contributed to turning the US occupation of Iraq into a quagmire and sharpening Sunni-Shia tensions in the country and region. Islamic State used territorial control on both sides of the Iraqi-Syrian border to declare a caliphate and launch or inspire deadly terrorist attacks from the region to Europe to North America and the Indo-Pacific.

A large international coalition built and led by the United States destroyed that “state”, but as we have seen the extremist group is still with us. And in Idlib province in Syria, a large contingent of Jabhat Al Nusra fighters controls a significant swath of land.

Meanwhile, 20 years after 9/11 and the invasion of Afghanistan, a local branch of Islamic State poses a significant terrorist threat, as its Aug 26 attack on Afghan civilians and US troops at the airport in Kabul shows.

Clearly such extremism is not a product of Western acts and policies. It is nourished by the problems of societies and political systems beleaguered by poverty, overpopulation, corruption and bad governance. Reform will have to come from within and not from without.

In any event, the United States has lost the will and perhaps the power to help bring such reforms about.

Its drift away from the Middle East derives from several sources, but the huge wasted investments in Afghanistan and Iraq and the recognition that such militant extremism is here to stay have played important roles.

Itamar Rabinovich is professor emeritus of Middle Eastern history at Tel Aviv University and distinguished global professor at NYU. This commentary first appeared on Brookings’ blog, Order From Chaos.