Commentary: What does it matter if Singaporeans spend their CDC or SG60 vouchers on ‘frivolous’ items?

For those who are still in two minds on how government vouchers ought to be spent, one approach is to donate a portion and spend the rest as they wish, says SUSS’ Terence Ho.

A CDC voucher sign at a heartland shop in Yishun on May 13, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Jeremy Long)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

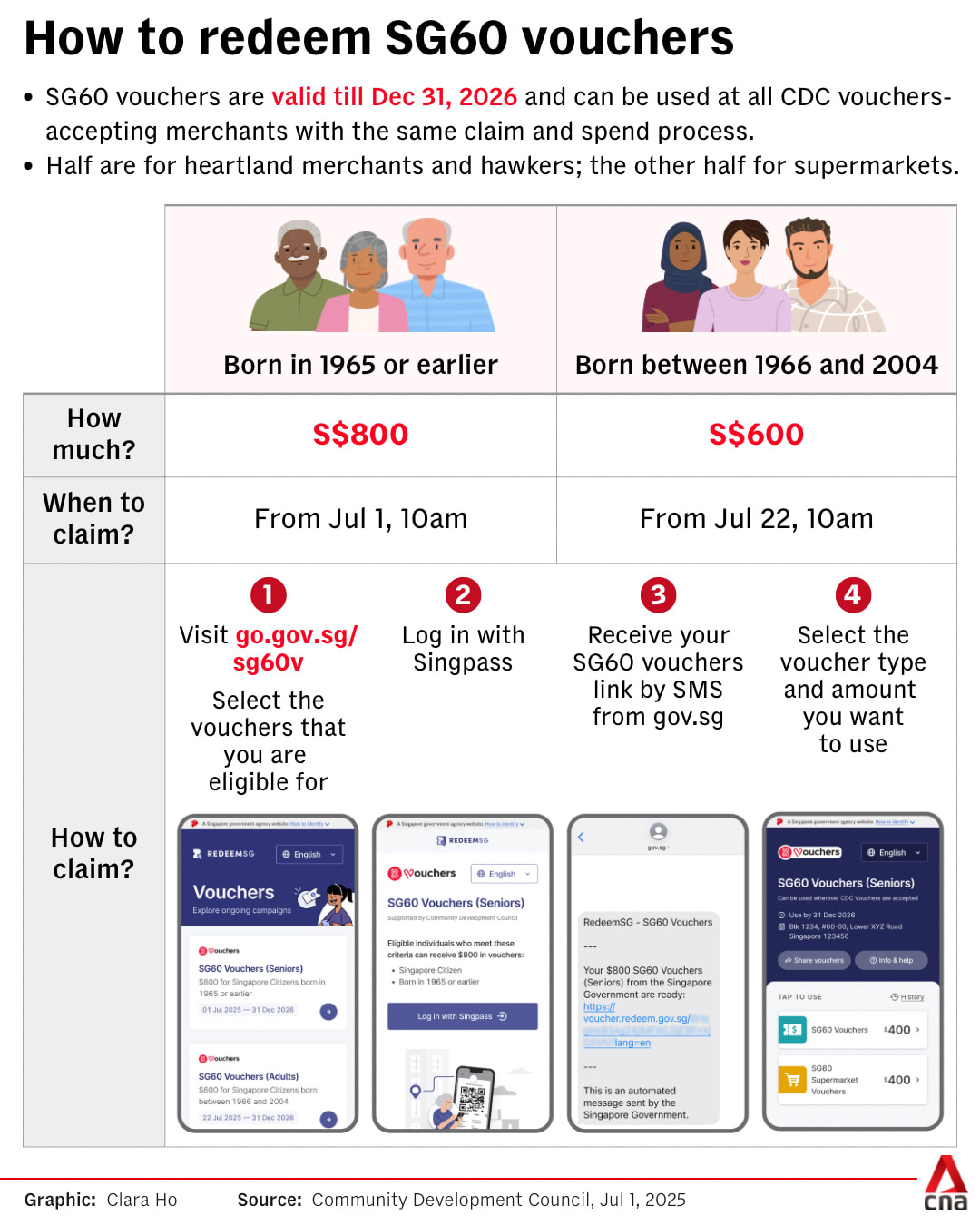

SINGAPORE: From this month, Singaporeans can start claiming their SG60 vouchers. Each adult citizen will receive S$600 in vouchers, while those aged 60 and above can claim S$800. This comes on top of S$800 in Community Development Council (CDC) vouchers which were given to each household earlier this year.

Retailers have lost no time in offering discounts and promotions to entice Singaporeans to spend their vouchers on their products and services.

However, a newspaper article published in May suggesting fun ways to make use of CDC vouchers – such as on dance apparel and craft workshops - prompted a flurry of online responses from netizens who felt that spending the vouchers on “frivolous” items went against the stated intent of the vouchers, namely to help Singaporeans with the cost of living.

IS THE ANGST JUSTIFIED?

The truth is that while the vouchers are a lifeline for some households and individuals struggling with high living costs, they are for others no more than extra pocket money or even spare change.

So is the angst over how the vouchers are spent justified? There are those who feel that SG60 vouchers should be distinguished from CDC vouchers in that the former are a celebratory gift while the latter are aimed at easing hardship.

Others are not bothered about how vouchers – whether CDC or SG60 – are used. Their view is that once public money passes into private hands, people should be free to do whatever they want with it. After all, whether the vouchers are used to buy bread or a fancy meal, the spending will ultimately benefit businesses and boost the economy.

Some have asked: Could the government have ringfenced the use of the vouchers to daily necessities?

It is hard to draw a clear line between essential and discretionary expenditure. Moreover, money is fungible – saving on any kind of purchase frees up financial resources for spending on other items.

There is a strong consensus among economists that giving assistance in cash or near-cash does more to improve consumer welfare than support that comes with conditions or restrictions because it offers recipients greater freedom of choice.

DIFFERING SOCIAL BENEFIT PARADIGMS

The crux of the issue may lie in differing concepts of what is prudent use of government money.

On the one hand, there are Singaporeans who prefer not to receive cash handouts or vouchers as they feel that such support ought to be channelled to the lower-income. This group is more likely to take umbrage at the use of vouchers for non-essential purchases.

Targeting government support at those who need it most is still the approach adopted for most forms of social support in Singapore. These include means-tested housing and healthcare subsidies, as well as permanent social transfers such as the Workfare Income Supplement, Silver Support and the Goods and Services Tax Voucher.

This paradigm of social support contrasts with models of universal welfare where social support is seen as a citizenship right. The latter, however, necessitates high taxes to enable extensive redistribution.

In Singapore, the government’s priority is to keep taxes on the middle class low in order to encourage work and enterprise. Under what is known as a “progressive” system of taxes and benefits, the rich bear a larger burden of taxes, while those with lower income receive more in social transfers or benefits.

Consistent with this approach, the Ministry of Finance estimates that the bottom 20 per cent of households by income receives around S$4 in benefits for every dollar of tax paid, while the top 20 per cent receive just S$0.30 for every tax dollar.

On the other hand, there are Singaporeans who feel that all citizens who contribute to the state’s coffers should be entitled to a range of benefits, and not just limited to public goods such as national security or infrastructure.

Some may feel aggrieved if they are excluded from certain benefits on account of their income or wealth, particularly if they are contributing a significant amount in taxes.

Like wealthy donors at a charity dinner who take pleasure in good food and a door gift, these high-income earners derive satisfaction from receiving vouchers and other Budget goodies, even if these offset only a small fraction of what they pay in taxes.

AN INJECTION OF UNIVERSALISM

Singapore’s approach towards social benefits is in fact evolving.

An early foray into universal benefits was the Pioneer Generation Package (PGP), introduced in 2014. The PGP provided a generous package of medical benefits to seniors born in 1949 or earlier, regardless of their income or wealth, to honour these pioneers for their contributions to nation-building in Singapore’s formative years.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic saw the government disburse a “solidarity payment” of S$600 to all adult Singaporeans in recognition of the broad impact of the pandemic on the population, with additional support given to seniors and families with children.

Rebates on utilities and service and conservancy charges, however, were tiered according to Housing and Development Board (HDB) flat type. Those who lost jobs or saw a significant fall in income could apply for further financial help through the COVID-19 Support Grant or COVID-19 Recovery Grant.

Taken together, Singapore’s COVID-19 support can be seen as a form of “progressive universalism” – where everyone receives some benefits, but those with greater needs receive more.

Following the pandemic, supply chain disruptions saw inflation shoot up across the world, including in Singapore. The government responded with a series of payouts to all Singaporeans in the form of CDC vouchers – the vouchers having the dual aim of providing cost-of-living support while giving heartland merchants a leg-up.

Notwithstanding these examples of universal benefits, most social support is still means-tested or tiered according to income or home value. There are advantages to having a mix of benefits – some universal and others means-tested with differing qualifying income thresholds.

This approach avoids a “cliff effect” where benefits drop off suddenly when one’s income crosses a particular threshold, which could discourage career and income advancement. Some elements of universality also make for greater inclusivity and sense of solidarity among citizens.

A MIDDLE WAY?

As inflation has receded from the post-pandemic highs, we may see fewer CDC vouchers disbursed in future. But for this year at least, vouchers are very much a part of the conversation.

Singaporeans who have no need for this support can easily donate unused vouchers to their preferred Institutions of Public Character via the CDC voucher website; they will even qualify for a 250 per cent tax deduction.

For those who are still in two minds on how government vouchers ought to be spent, perhaps a good strategy would be to set aside a portion of the vouchers to give away, and then spend the rest on whatever you wish with a clear conscience.

Terence Ho is Associate Professor (Practice) at the Institute for Adult Learning, Singapore University of Social Sciences. He is the author of Future-Ready Governance: Perspectives on Singapore and the World (2024).