Commentary: Is Hong Kong now just another Chinese city?

Hong Kong is becoming more Chinese, and as a result may become less of a draw for multinational corporations, says Christian Le Miere.

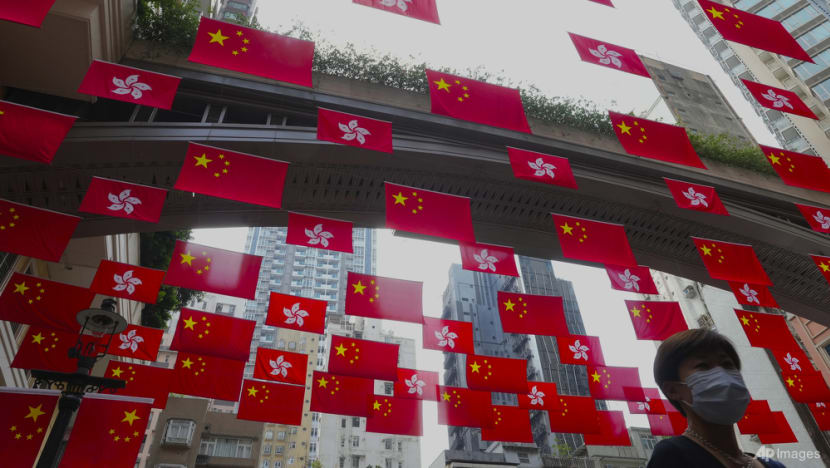

A man walks past Chinese national and Hong Kong flags in the background at a street marking China's 72nd National Day in Hong Kong Friday, Oct. 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Vincent Yu)

HONG KONG: Hong Kong is about to reopen. After a long pandemic that has seen travel collapse, this most international of cities is getting ready to throw its borders open again.

But there’s a catch. The territory is only opening its borders one way – to China. For the rest of the world, entry into Hong Kong is about to get harder, rather than easier.

Last Friday (Nov 5), Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam said she expects Hong Kong’s borders with China to open up on a “large scale” by February.

Yet just over a week earlier, on Oct 26, Lam also announced that visitors from overseas beyond China will have even tighter restrictions for entering the territory.

Hong Kong maintains one of the stiffest COVID-19 entry policies in the world, with almost all visitors subject to mandatory 14- or 21-day hotel quarantines. Exemptions for some travellers, such as diplomats and business leaders, have been cancelled.

It is unsurprising that Hong Kong would prioritise its border with China over the rest of the world – when they are part of the same country and China has been Hong Kong’s largest trade partner since 1985.

But China’s zero-COVID policy means that the decision to open up to China necessarily means closing down to the rest of the world. As such, Lam is reinforcing a perception that has been apparent since the middle of 2020 – that Hong Kong is now a Chinese city, and less of an international city.

HONG KONG BECOMES MORE CHINESE

A shift in Hong Kong to becoming more of a Chinese city rather than an autonomous and international territory has been underway, cemented with the passing of the national security law in late June 2020.

Since then, the protest movement in Hong Kong has been curbed, leading opposition figures and organisations disbanded or driven overseas, and publications such as Apple Daily have been muted.

Elections have been postponed, raids conducted against a suite of opposition figures, protests outlawed, and legislators sympathetic to the protests banned from the unicameral parliament while the rest of the opposition resigned.

Electoral reform has made it harder for political candidates associated with the protests to build momentum by reducing the number of directly elected legislators and ruling that only vetted “patriots” can be candidates for political office.

These new reforms are also touching everyday aspects of society. In late October, the Hong Kong government passed a new movie censorship law that will “safeguard national security”.

Self-censorship has already taken hold of the city owing to the extra-legal arrest and extradition of several Hong Kong booksellers. This atmosphere has also trickled down to education – where teachers can now be fired for “subversive” classes, while all subjects must now include material on national security in order to ensure a patriotic curriculum.

HONG KONG MAY BE LOSING SOME OF ITS LUSTRE

These are significant changes for a territory with a very different history and ethos from much of mainland China that have fuelled concerns for multinational companies.

Hong Kong has built a reputation for an open and business-friendly economy, autonomy from China, a vibrant civil society and a highly international population to enable it to become one of Asia’s key financial hubs.

The city remains a regional hub and its access to China gives it a unique competitive edge over other regional cities such as Singapore. Yet the number of overseas companies with regional headquarters fell from 1,504 in 2020 to 1,457 in 2021, while the number of mainland Chinese companies with regional headquarters increased from 238 to 252, according to census data.

The territory’s population is also shrinking – by 1.2 per cent in the first half of the year, as residents vote with their feet.

This is partly owing to the pandemic and departure of foreign residents seeking to spend more time with families back home, but there are signs showing many residents are also leaving.

More than 450,000 British National Overseas passports were issued to Hong Kong residents in 2019 and 2020, in a city with a population of just over 7 million, peaking in late 2020 at more than 50,000 issued each month after the UK government announced new visa rules granting the right to live and work in the UK with a BNO passport.

At least 8,000 residents leaving Hong Kong withdrew £2.1 billion (US$270 million) from the Mandatory Provident Fund pension scheme in the second quarter of 2021.

This figure is up 112 per cent from the same period in 2020 and accelerating: In the first quarter of 2021, 7,700 claims were made and HK$1.93 billion (US$250 million) withdrawn, a 49 per cent year-on-year increase.

Inflows have also been falling, with the total dropping to HK$10.5 billion in the third quarter of 2021, according to Bloomberg, the lowest since 2018 as more residents retired early or left the city.

Meanwhile, more mainland Chinese are arriving and sinking roots. Over 30 per cent of luxury property purchases in the city in the first half of 2020 were by mainland Chinese.

A one-way visa scheme allowing 150 mainland Chinese to enter Hong Kong each day and be reunited with their families has seen more than a million migrate since 1997, making up just under 15 per cent of the city’s population.

HONG KONG’S FUTURE

These trends are troubling for Hong Kong’s future as an autonomous territory, but they have not yet undermined its status as a regional hub.

It is still early to say if the city’s zero-COVID policy or the political changes over the past year are a bigger driver.

The territory’s access to China’s capital markets still make it an attractive location to access mainland China while still benefiting from an international city with a separate legal system.

The preservation of judicial independence will be critical - the primary reason multinationals have enough trust in the city to base headquarters there.

Being able to rely on the rule of law to ensure contracts are upheld or disputes resolved apolitically makes Hong Kong a stable and predictable place to do business, combined with its unique position as part of China.

Should there be an indication that judicial decisions or appointments are being swayed by mainland Chinese concerns, then firms might ask why not just move to Shenzhen or Shanghai for your China headquarters and have a regional base in Singapore?

Already, international companies and migrants in the city are worried they may fall foul of the broad-based national security law.

In the wake of COVID-19, as Hong Kong opens to China first before the rest of the world, the Sinification of Hong Kong will likely continue. The effects, though, are not just practical but also symbolic.

Effectively, Hong Kong is now signalling that its future lies within and as part of China, and less as an international city.

Christian Le Miere is a foreign policy adviser and the founder and managing director of Arcipel, a strategic advisory firm based in London.