Commentary: Recent clashes at Chinese companies in Indonesia might be fodder for political manipulation

A fatal incident in January involving a Chinese-owned mining company raises the spectre of political opportunists exploiting anti-Chinese sentiments in the run-up to Indonesia’s 2024 elections, say these writers.

File photo. People cross a main road outside a shopping mall in Jakarta, Indonesia on Nov 30, 2022. (Photo: Reuters/Willy Kurniawan)

SINGAPORE: On Jan 14, an Indonesian and a Chinese worker were killed during protests at the Gunbuster Nickel Industry smelter. The smelter, owned by China’s Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry, is in Morowali district, Central Sulawesi.

Conducted by workers demanding better safety conditions and pay, the protests were the latest in a string of industrial clashes in Sulawesi. These have occurred as the island experienced an investment boom in nickel mining, as nickel is a vital component of batteries for electric vehicles, an industry that Indonesia is keen to develop.

These incidents highlight the importance of government monitoring of work conditions. When violence occurs, this aggravates broader negative sentiment about Chinese investments in Indonesia.

As the 2024 elections approach, there is a risk that such incidents can be exploited by elements who may be eager to inflame anti-Chinese sentiment for political gain.

CHINA IN CAMPAIGN RHETORIC

As China’s economic rise has proceeded apace, recent electoral campaigns in some Asian recipients of Chinese investment have featured anti-Chinese rhetoric. In 2018, oppositions in Malaysia and the Maldives won elections after criticising their incumbent governments’ pro-China policies.

During Indonesia’s 2019 election, then presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto lamented the government’s decision to permit a large influx of Chinese workers into Indonesia. This was a precarious electoral strategy, as voters could have conflated his criticism with longstanding resentment against ethnic Chinese Indonesians’ perceived and actual economic dominance. Especially for Prabowo’s conservative religious supporters, such a conflation would have reinforced their sectarian agenda.

Sectarianism, especially that caused by prejudice against Chinese Indonesians, is irrational. More than 50 per cent of respondents in the Indonesian National Survey Project 2022, for example, believe that Chinese Indonesians “may still harbour loyalty towards China”. This finding suggests that stereotypes about Chinese Indonesians remain strong.

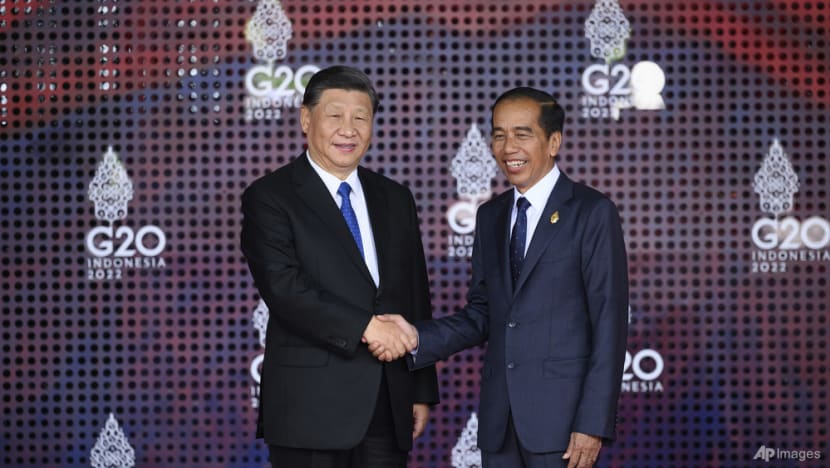

As criticism of President Joko Widodo’s pro-China policies drove some of the opposition’s 2019 campaign rhetoric, it is possible that such tactics will be used against any 2024 presidential candidate who shares his outlook. Detractors might disregard the risks of inflaming ground sentiment to stoke support for their own candidate.

Shortly after the January incident, Deputy Chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council, Anwar Abbas, a Widodo critic, suspected that “what the Chinese extracted is much more than what they have reported to the government”, essentially alleging that Chinese companies might be engaging in misconduct. In 2020, Abbas alluded that the Omnibus Law (on job creation) was an attempt to attract foreign investment from China.

Separately, the Prosperous Justice Party’s member of parliament Mulyanto claimed that the government was “soft on Chinese investors and hard on local workers”. He urged that Gunbuster Nickel Industry’s licence should be revoked if it has violated regulations.

INFLOW OF CHINESE GUEST WORKERS TO INDONESIA

China is one of Indonesia’s largest investors, with US$3.2 billion of investments in 2022, and has been Indonesia’s largest trading partner for the past nine years, with 2022’s trade volume reaching US$124.3 billion. These trends have led to a steady inflow of Chinese guest workers, who now make up about 44.34 per cent (about 42,900) of all foreign workers in Indonesia.

Some naysayers have linked the concern surrounding such numbers of Chinese workers with anti-Chinese sentiments.

In 2021, the aforementioned Mulyanto, whose parliamentary commission supervises the energy and industrial sectors, alluded that Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Panjaitan was responsible for the influx. Mulyanto’s claim that these workers were unskilled was echoed by other Prosperous Justice Party politicians who also lamented the government’s decision to permit their entry amid COVID-19 restrictions.

In mid-2022, former Jakarta governor and former head of the State Intelligence Agency Sutiyoso expressed “concern” that these Chinese workers would never return to China. He added that they would multiply in Indonesia and that people of Chinese descent would dominate the country, mentioning Malaysia and Singapore as examples.

Sutiyoso considers himself a nationalist and had joined the National Democratic party in 2021. Whatever Sutiyoso’s motivations, his past jobs would mean that he understands the dangerous implications of making such claims.

There has been some pushback against Sutiyoso’s rhetoric. The Indonesian Solidarity Party’s Chinese Indonesian politician Grace Natalie considered his remarks racist ones, which could cause a rift in Indonesian society. Garuda Party politician Teddy Gusnaidi suggested that Sutiyoso might have violated Law No 40 (2018) on the Elimination of Racial and Ethnic Discrimination.

OLD NARRATIVE OF A COMMUNIST THREAT

Such anti-Chinese fearmongering illustrates a persistent obstacle in Indonesia’s management of ethnic issues. For as long as some political elites treat Chinese Indonesians as outsiders whose number and access to certain jobs or resources should be curbed, sectarianism will persist.

Separately, the Chinese workers issue has fed into the hoary narrative of a communist threat. About 46.4 per cent of 1,000 respondents in a 2021 poll believed it was possible communism could be revived in Indonesia.

While the survey question may be biased, with mostly China-related options, respondents linked this possibility to the large number of Chinese workers (chosen by 12.3 per cent), Indonesia’s dependence on Chinese COVID-19 vaccines (11.8 per cent), China wanting to annex the Natunas waters (9.4 per cent), and China’s control of Indonesia’s economy (9 per cent). Earlier, 26 per cent of 1,203 respondents in a 2020 poll by a different institute believed that China-Indonesia relations could revive communism.

It is possible that some politicians and their supporters could exploit anti-Chinese ground sentiments to gain votes come 2024. It is incumbent on the central government to prevent or limit the fallout from recent and future Chinese-related industrial clashes that could aggravate such sentiments.

Deasy Simandjuntak is Associate Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore, and an Assistant Professor at National Chengchi University, Taiwan. Aswin Lin is a PhD candidate at the International Doctoral Program in Asia-Pacific Studies, at the National Chengchi University, Taiwan. This commentary first appeared on the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute's blog, Fulcrum.