Commentary: Pandemic fails to shift Japan’s attitude to employee well-being

Japan's stance on remote work can be viewed as resistance to broader change, says the Financial Times' Leo Lewis.

TOKYO: In the early months of 2020, as it became clear to the world that the COVID-19 pandemic would require an immediate and radical response, corporate Japan contemplated a near overnight move to remote working.

The prospects did not seem good; the results have been revealing.

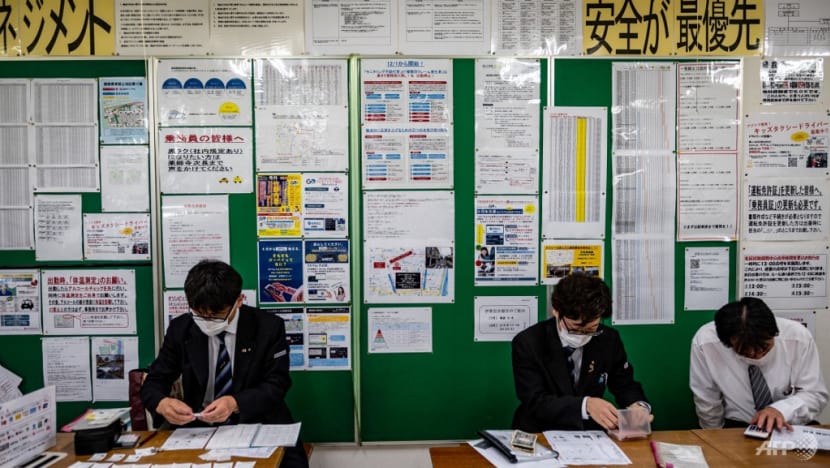

Over decades, the Japanese workplace had established many practices and habits which together helped create a reputation for inflexibility, resistance to change and an institutional dismissiveness over the well-being of staff.

Structural pressure to overwork, presenteeism, the persistence of certain archaic technologies, and a downplaying of mental health issues and abuse are just some of the most-cited factors in analyses of Japanese workplace pathology.

Even as the benefits of remote working to quality of life became clearer and employees sought flexibility to care for children or, increasingly in the world’s most rapidly ageing society, elderly relatives, companies resisted.

DO EMPLOYEES OWE THEIR EMPLOYERS ANYTHING?

A big part of the resistance has involved fear that hierarchies will crumble and the pervasiveness of the idea that something is “owed” by the employee to their employer that goes significantly beyond the work contract.

Expressions of that mindset abound. In a 2019 survey by Expedia comparing the number of paid vacation days versus the number actually used among G7 countries (as well as South Korea), Japan placed last.

In the United Kingdom, Canada, France and Germany, the ratios were all near or above 90 per cent. In Japan, where the ratio was just 50 per cent, respondents described feelings of guilt about taking paid holidays in a time of labour shortage and the fear of being seen not to want to work.

In many cases, workplace inflexibility has persisted despite strengthening public criticism, employee distress, government attempts at top-down reform and even tragedy.

AROUND 3.6 MILLION WORK AT LEAST 60 HOURS A WEEK

The “death by overwork” of a 24-year-old advertising executive at Dentsu in 2015 was widely interpreted at the time as a watershed moment, and prompted many companies to rewrite their rules on overtime.

There has been some progress since then but, say experts on workplace well-being, it has been slow.

In 2017 - the year in which Dentsu was formally charged over the death of its employee - total average hours worked by Japanese fell by five hours from the previous year, to 1,926 hours.

In 2018 the average fell by 25 hours and in 2019 by 32 - a trend cautiously welcomed by advocates of higher workplace well-being standards.

The same government labour force survey found that the number of workers putting in at least 60 hours a week was 3.6 million in 2020 - a decline of 1.57 million from 2017.

The mothballing of many businesses and operations at the onset of the pandemic meant there were significant distortions to those trends during 2020. However, in 2021, the hours began creeping higher again.

CORPORATE CULTURE

The big question, as Japanese workplaces now return to some post-pandemic normality, is whether the past two-and-a-half years will result in permanent change.

The initial surprise, when Japan entered a period of voluntary lockdown in 2020, was how many larger companies were able to make the leap to remote working. The assumption had been that many companies had neither the technology nor cultural propensity to embrace remote work. The fact that it took a crisis to demonstrate it was entirely possible provoked fury in many workplace chat rooms.

In June 2020, a study by Keio University suggested that, in some cases, the transition had been quicker than hoped, though mainly for large companies.

As a national average, the rate of remote working jumped from 6 per cent in January 2020 to 17 per cent in June.

In some professions, such as administrative workers, management consultants and data processors, the percentage rose above 30 per cent; for many others, the needle barely budged. One year later, the study’s researcher, Toshihiro Okubo, found the rate of remote work was essentially unchanged.

The prevalence of remote work, he concluded, remains low in Japan because of corporate culture. Many Japanese companies, he says, have a long tradition of staff working together in the same room within the office and have a hierarchy with tight communication and lots of internal consultation.

“This system works well in team-based tasks, informal information-intensive work, less discretion, less autonomy and more exchange of tacit knowledge . . . however, our findings suggest that all of those are unsuited to remote work,” says Okubo.

The risk to employee health, at this point, is that Japan returns to post-pandemic normality without any significant corporate reset in attitudes towards wellness.

“The past couple of years have highlighted the need to rework the Japanese office workplace and to more rapidly accelerate an understanding of the critical importance of wellness,” says Peter Eadon-Clarke, an adviser to the Asian wellness consultancy Conceptasia.

“Initiatives to reduce long working hours and stress, by both the government and private sector, have been slow and steady, but the need for urgency is now obvious.”

A survey by market research company Intage strongly suggested that workers themselves are even more pessimistic. In a report released in April, it found that just 18 per cent of workers surveyed said their working style had changed during the pandemic, and just 13 per cent predicted that those changes would be permanent.

Japanese workers, better than anyone, know precisely how hard-drawn are the invisible lines in the workplace. They also know it will take more than an unprecedented global pandemic to shift them.