Commentary: Singapore was built on Lee Kuan Yew’s ideas - which are still relevant today and which are not?

As Singapore marks the 100th anniversary of Lee Kuan Yew’s birth, former veteran newspaper editor Han Fook Kwang – who authored several books on the late founding Prime Minister – reflects on Mr Lee’s enduring vision for the country.

File photo of Lee Kuan Yew. (Photo: AFP/Toshifumi Kitamura)

SINGAPORE: When Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore, was once asked how he would like to be remembered in history, he replied in typical fashion that he would be dead by then and it would not matter to him.

He was not one to care about what others thought of him, least of all when he was long gone.

But he was concerned about Singapore’s future and in his later years he wrote and agreed to be interviewed extensively on what was needed to ensure it could continue to thrive and prosper.

He lamented that a younger generation took for granted Singapore’s success and did not understand how it overcame the odds to become the thriving city it is today.

As Singaporeans commemorate the first centenary of his birth, eight years after his death in March 2015, it is fitting to pose the question: Which ideas of the man about nation building are still relevant today and which are not?

SINGAPORE’S EVOLVED FROM THE COUNTRY LEE KUAN YEW GOVERNED DECADES AGO

The answer to the first is a long list: Incorruptibility, meritocracy, exceptionalism, leadership, openness to the world, multiracialism.

He had strong views about each of these and all of them were important in shaping Singapore’s development through the years.

But there are questions and issues now over every one of these ideas, as new challenges emerge.

Singapore is no longer the same country Mr Lee had governed for more than 30 years and the world has changed.

Meritocracy isn’t as simple as just choosing the best for the job. What if the best are perceived to have had an unfair advantage over others because they had wealthier parents able to give them a head start in life?

Also, the meritocracy that Mr Lee championed was based largely, though not completely, on academic credentials and he was famous for highlighting a person’s past school results as a mark of his superiority over another.

Today, such a narrow definition would be considered elitist in nature and not politically correct.

Singapore’s exceptionalism was largely a result of Mr Lee’s conviction that it had to be better, more efficient and productive than its neighbours or it would not survive.

He was single-minded about pursuing economic growth believing that it was the prerequisite to achieving all the other finer things found in advanced societies.

Even in his later years when we interviewed him for the book Hard Truths To Keep Singapore Going, which I co-authored in 2011, and put it to him that growth at all costs had undesirable side effects such as being overly reliant on cheap foreign labour and had to be tempered with redistributive policies to help narrow the income gap, he was adamant there was no other alternative.

“We should grow as fast as we can sustain that growth. If we can make that growth and we choose not to, then we are stupid … We get slow growth and we will have fewer jobs and lower pay, less this, less that, less everything,” he said.

Today, much of the political discussion is not over growth per se but how to do more to help lower-income workers, even as those at the top continue to accumulate unimaginably large wealth.

It is not that Mr Lee was not concerned with those at the bottom. He and his team lifted an entire generation out of poverty within the first 15 years of independence.

But he favoured the simpler idea over the overly complicated.

He wasn’t interested in theory or the elegance of an argument. Building a nation was too important and urgent a task, and he was impatient for results.

He put it this way in the book Lee Kuan Yew: The Man And His Ideas, which I co-authored in 1997.

“We were not ideologues … I’d read up the theories and maybe half believed them. But we were sufficiently practical and pragmatic enough not to be cluttered up and inhibited by theories. If a thing worked, let’s work it, and that eventually evolved into the kind of economy we have today … Our test was: Does it work? Does it bring benefits to the people?”

THE FORCE OF HIS PERSONALITY

Perhaps the simplest of his ideas was on leadership. A country needs the best to govern, so go out and get them, and pay them well to make it an attractive proposition.

You can’t argue with the cold logic, and he used the force of his personality to bulldoze his way, introducing a formula to pay ministers top salaries.

It worked only while he was around, and there have been changes to the formula since to take into account public unhappiness over the issue.

But ministers are still relatively well paid.

The idea that political leadership was critical to Singapore’s success persists.

It is testimony to the power of his influence, even today, as are his ideas on meritocracy, multiracialism and incorruptibility.

Their raw edges may have been refined and the policies associated with them changed to take into account changing circumstances and the needs and expectations of the people.

Mr Lee recognised this. In Hard Truths, he would demur whenever we asked him for his views on current policies.

Ask the younger ministers, he would say, sometimes adding that he wasn’t in touch with what was happening on the ground.

He wasn’t fixated on one way of doing things just as he wasn’t enamoured with theory.

But engage him on the fundamental issues of leadership, meritocracy, incorruptibility and multiracialism, and he would be unyielding.

He wasn’t right on everything, of course. He was quite wrong on the value of early preschool education to help children of low-income families.

I can remember at least once when he gave editors an earful over a newspaper report of one kindergarten offering some new way of teaching young kids.

You’re encouraging parents to waste money sending their children to these schools, he would decry. He was of the view that by the time they were 10 years old, their innate intelligence or lack thereof would determine their school grades never mind whether they attended these preschools.

Later research proved him wrong, the government changed course, and early education is now receiving the attention it deserves.

DIFFERENT, BUT STILL THE SAME

The one thing he would most want to remain unchanged is the idea of Singapore itself.

What is this unlikely country that he was instrumental in transforming from Third World to First?

Has the Singapore idea changed with this transformation?

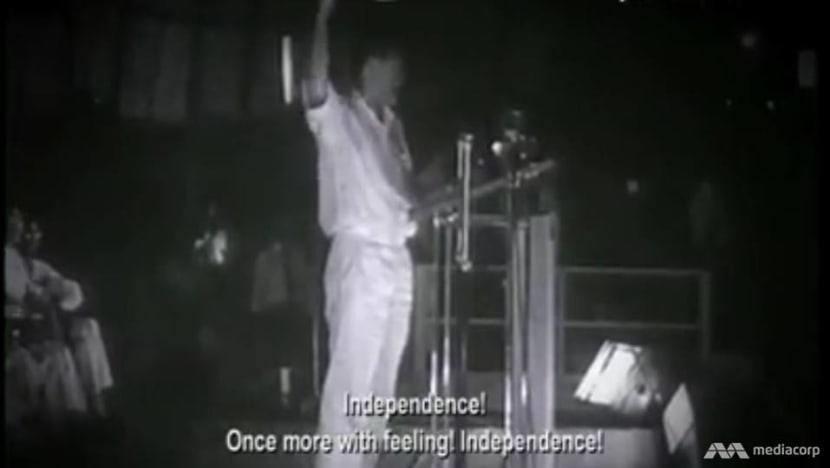

Is its identity different from what it was when it gained independence in 1965, now that it is wealthier, more secure and less vulnerable?

Amid the uncertainty of a rapidly changing world, Singaporeans need to be even clearer what the answer is.

I think Mr Lee would have replied that it has not changed.

In Hard Truths, when we asked him what it was about Singapore he most dearly wanted Singaporeans to identify with, he said: “This is a near miracle. When you come in, you are joining an exceptionally outstanding organisation. It's not an ordinary organisation that has created this. You’re joining something very special.

“It came about by a stroke of luck … plus hard work, plus an imaginative, original team. And I think we can carry on. Singapore can only stay secure and stable provided it’s outstanding.”

Everything else flowed from this one central immutable idea.

Depart from it, and he would, as he famously once said, jump out of his grave to put it right.

Han Fook Kwang was a veteran newspaper editor and is Senior Fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.