Commentary: 10 years after Lee Kuan Yew’s death, have Singaporeans abandoned his staunch belief of Singapore’s vulnerability?

After Lee Kuan Yew's death in 2015, the vulnerability narrative has lost its appeal among Singaporeans today, especially among the young, says veteran newspaper editor Han Fook Kwang.

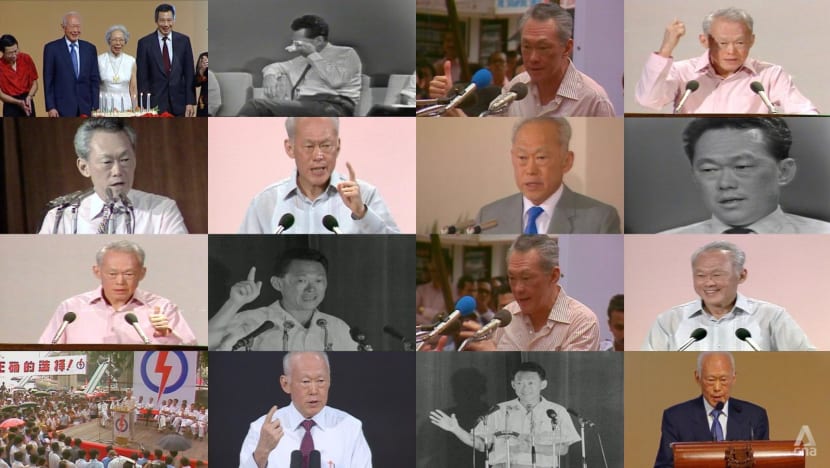

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's founding prime minister.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: If Lee Kuan Yew were alive today, would he jump out of his sick bed as he famously promised and try to stop the downward slide he feared Singapore could head towards? Or would he afford himself a satisfied smile that the island state was in good hands and doing as well as could be expected?

Ten years after his death in 2015, contrary to the claims of some of his critics, Singapore has not followed him to his grave. That might give him some satisfaction, though, being the country’s worrier-in-chief when he was alive, he would never be completely satisfied.

And there is one nagging concern about Singapore today that he would be distressed about; but more on this later.

On the plus side, according to various measures of success, such as economic wealth, life expectancy and educational attainment, Singapore has become better and stronger.

These achievements were made in ways that have not departed much from the principles that he held dear to and which guided his 25 years as prime minister of independent Singapore.

There has been no fundamental change in the approach of the 3G and 4G leadership towards nation building.

This is not to say it has been entirely smooth sailing for the Singapore ship.

PERIOD OF UNCERTAINTY

Economic growth has slowed down sharply compared to the double-digit growths of the 1970s and 80s, incomes have become more unequal between the top and bottom segments of the population and there have been surprising political hiccups in recent years, including on the issue of leadership succession.

As a result, it is not uncommon these days to hear murmurings among the people when things have not gone well, that if “LKY were around….” or “he would have done it this way...”.

No one is saying Singapore needs another Lee Kuan Yew but neither has the intervening 10 years been so stress-free that there has not been the occasional wish for his counsel and vision.

In a period of uncertainty and rapid change - which the world now faces on the geopolitical and technological front - there is always a tension between wanting to break free from the past to chart new paths and a return to the good old days of greater certainty and stability.

Singapore feels this pull more sharply because it has achieved so much in so short a time that memories have not faded completely, including of Mr Lee and his remarkable leadership.

On the 10th anniversary of his death, it is pertinent to ask what was his most compelling idea of Singapore that made it overcome the odds and shaped his thinking about its survival and success, and which might still be relevant today.

Most people when asked would trot out the usual answers: Law and order, corruption-free government, meritocracy and multiracialism. These are important, but they came later.

At the beginning, and more than anything else, was this core idea: Singapore is a highly vulnerable country with less margin for error than most countries, which is why it needs to be constantly tended and closely governed by the best and brightest who have to come forward to serve as leaders.

In the book Hard Truths To Keep Singapore Going, he put it this way: “This place is like a chronometer. You drop it, you break it, it’s finished… I’m not sure we’ll ever get a second chance… If you believe this superstructure is the same as other countries, you are dead wrong.”

This, for him, is the one idea that he would dearly wish would outlast him.

THE VULNERABILITY NARRATIVE

In his last years of his life, he devoted time and energy, through various books and interviews trying to impress on the young whom he felt had taken the country’s success for granted.

I mentioned at the beginning that he would be very vexed today over one development - and it is precisely this because few people now believe Singapore is as vulnerable as he made it out to be.

It is an existential issue for him because it is not just a slogan to rally the people but it drove and shaped policy and philosophy.

He used it to great effect to shake up the public service and get the people to work harder, be better organised and disciplined to make Singapore an exceptional place in Southeast Asia.

For the population, being told they were in a do-or-die mission is a double-edged sword. It can light a fire in them or make them lose heart resulting in an exodus of the best.

For the latter not to happen, leaders have to offer hope and a vision for the future. Mr Lee and his team did that.

The vulnerability narrative was also necessary to attract capable people into politics, appealing to their sense of public service for a higher cause.

But it is a narrative that has lost its appeal among Singaporeans today, especially among the young.

This is not unexpected, and perhaps inevitable, being the price of success.

How can Singapore be vulnerable when it is one of the richest countries in the world measured by gross domestic product per capita, with one of the highest government reserves and a magnet for foreign billionaires?

I have no doubts that were he alive today and asked the question, every fibre in his body would stiffen, his gaze fixed with eyes glistening and his voice would thunder: “If you don’t believe it, we are dead!”

In every one of the interviews I have had with him on this issue, he was unwaveringly consistent.

STILL VULNERABLE, IN A DIFFERENT WAY

If Singaporeans want to remember the man on this day, it is this idea of Singapore’s vulnerability that he would wish they take to heart.

But it has to be narrated in a different way from his because Singapore and the world have changed and the challenges are no longer the same.

Singapore is no longer a Third World country struggling to make it.

It is a different world now though the realities of the island state and its neighbourhood have not changed.

Indeed, many have argued that it has become more dangerous.

The upheaval in the international order wrought by American President Donald Trump’s new vision to remake his country and its consequences on trade, technology, United States-China relations, and ultimately, war and peace, have made it more uncertain for Singapore, given its open economy and reliance on trade and foreign investments.

Singapore is still vulnerable but in a different way.

It requires a narrative with the same theme but different setting, actors and plots.

If the leaders of Singapore, on both sides of the political divide, want to commemorate Mr Lee’s legacy on his 10th death anniversary (Mar 23), they could offer their versions of what this new narrative should be.

Han Fook Kwang was a veteran newspaper editor and is a senior fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.