Commentary: The untold story behind Max Maeder’s Olympic medal - former national sailor Ben Tan gives an insider's view

Max Maeder’s Olympic medal was won through deliberate engineering - by him, his parents and Singapore’s extensive sports ecosystem, says former national sailor and Olympian Ben Tan.

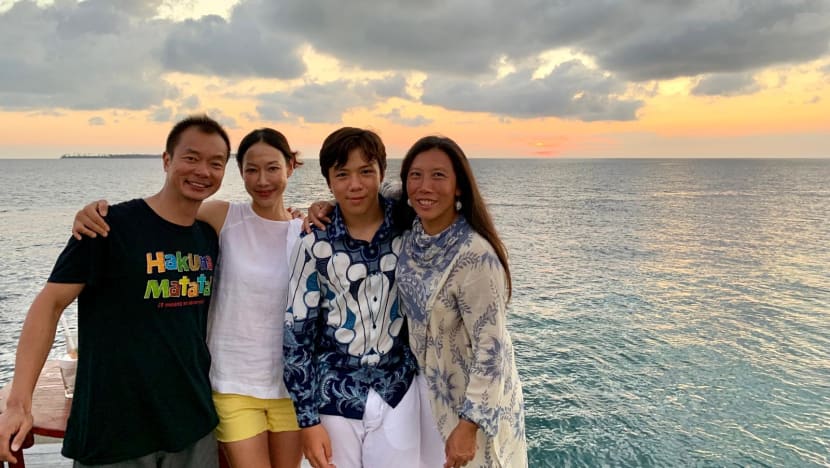

Kitefoiler Maximilian Maeder has won a bronze for Singapore at the Paris Games, making history as the country’s youngest Olympic medallist.(Photos: Hwee Keng Maeder; AFP/Clement MAHOUDEAU)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

MARSEILLE: In 2018, a close friend of the Maeder family and a fellow kiteboarder alerted me to a wonderkid on the professional kite racing circuit.

“Ben, you know Max Maeder? You have to meet him,” the friend said.

The following year in August I headed to Wakatobi, an island off Sulawesi, to “check out” this kid. It’s a remote island accessible only through twice-weekly charter flights from Bali, and a great place for diving and kiting.

There, I was introduced to a 12-year-old Max, a well-dressed, articulate and earnest-looking boy.

The way he handled an oversized kite and foil board with plain ease was impressive to say the least. Further conversations with Max and his parents, Valentin and Hwee Keng, as well as my observations of Max’s training ethic and approach to life convinced me that I had stumbled upon someone special.

THE ROAD TO KITEFOILING

How does one become a kitefoiler?

You start by learning how to kiteboard. A background in sailing, surfing or wakeboarding would be useful but not essential. The first component is launching, steering and landing the kite. The second is getting up on the kiteboard (a flat board with small fins at both ends) and staying on top of it.

Most would be up and riding within five days. Then, with lots of water time, one gets comfortable enough to start learning tricks like riding toe-side and jumps. Perhaps a year or more later, you’re ready to transition to a foil board.

In kitefoiling, the hydrofoil beneath the board generates lift to elevate the board above the water, greatly reducing drag and increasing speed. The powerful foil kites and low drag hydrofoils allow riders to fly over the surface of the water at speeds faster than the wind, sometimes exceeding 40 knots (75 kmh).

Controlling the height of the board above the water is crucial and unique to foiling. A mistake could lead to a nasty fall. Note that Max wears a helmet, goggles, impact vest and a wetsuit for protection.

Kiteboarding is one of the fastest-growing sports in the world. You don’t encounter that many of them because kiters mostly use designated kite beaches. It’s too dangerous for kiters and swimmers to share the same beach.

On my kitefoiling trip to Tarifah at the southern tip of Spain last November, there were hundreds of kites on the water, and that was off-season. The competitive kitefoilers you saw during the Olympics represent the tip of a very big pyramid.

MAX’S EARLY BEGINNINGS

In this elite field, the current world champion and Olympic bronze medallist is Singapore’s very own Max Maeder.

He began kiteboarding at age six, thanks to his parents Valentin and Hwee Keng, who were also kiteboarders. A ride on a kitefoil soon after with professional kiter Marvin Baumeister turned Max’s attention to kitefoiling.

From age 11, Max honed his skills on the professional circuit, racing against adults. Six world youth titles and two senior world titles later, Max delivered Singapore’s very first Olympic medal in sailing, and Singapore’s sixth Olympic medal, all at the tender age of 17.

There are no shortcuts to nurturing a sailing champion. The first ingredient is water time, which Max had plenty of growing up on Wakatobi. Homeschooling meant his academic lessons could be wrapped around his training, while plying the professional circuit added the intensity.

Next is his upbringing and parental influence. The Maeders’ parenting style might be counterintuitive to some - major life decisions are answered with a “why not”. Homeschooling was a natural decision for the Maeders, and so was racing (sometimes unaccompanied) on the professional circuit among adults.

Father Valentin is an accomplished glider pilot, and brings with him a deep understanding of aerodynamics, meteorology, and physics and risk management. Meanwhile, Max’s mother Hwee Keng, with a degree in psychology, ensures that her parenting decisions, even those that may seem reckless (for example, allowing a child to travel alone), are carefully considered.

NOT YOUR TYPICAL TEENAGER

Their parent-child relationship has strengthened through what for others are the “terrible teen” years. I don’t think they’ve even encountered the “terrible teens” as Max does not behave or think like a typical teenager. He doesn’t party or let his teenage curiosities get the better of him. He is highly responsible, self-sufficient, independent, and safety conscious. When he was 12, I witnessed him diplomatically lecturing a much older kiter over a kiteboarding safety breach.

He talks to his father daily, even when he is racing somewhere in Europe while his father is in remote Wakatobi. Time zone differences don’t matter. Max knows he can call Papa anytime, and Valentin doesn’t mind being woken up at 3am for a chat. No topic is taboo.

Digging into Max’s psyche, I asked him why he talks to his father daily, despite his packed routine. His answer was that he genuinely is looking for advice and that his father provides a safe space. Pressing further, I asked Max how he handles it when he knows his father’s feedback might be tough to hear. His answer? “I’m a rip off the band-aid kind of guy.”

While on the circuit and during the Olympics, these daily chats serve as pre-race “framing” sessions and post-race debriefs. The pre-race chats are short, designed to get Max in the optimal frame of mind. They cover the day’s objectives, priorities, the controllables and non-controllables, and technical information from Max’s team.

The post-race debrief is more detailed, with Max sharing what he did well or not so well. Valentin acts as a sounding board and does not tell Max what to do. Max is trained to make his own decisions on and off the water, and over the years has been consistently imbibed with mantras like, “know thyself”, “regulate thyself”, “certainty brings ruin” and “question your constructs”.

THE SLINGSHOT

Sailors deal with elements that they cannot control, but they can make educated predictions and calculated moves based on whatever is thrown at them.

Max is excellent at calculating and managing probabilities. I like the phrase Valentin often uses, “probability cloud”. No sailor can get it right 100 per cent of the time - there is an element of chance and luck, especially in light wind conditions. That’s why sailing outcomes are decided over many races and days.

During the Olympics, 16 races were scheduled for the opening series, of which races eight to 16 were cancelled due to lack of winds. For the finals, only three races were held.

In his extensive racing experience, this is the first time Max has encountered so many cancelled races.

Despite being the youngest in the fleet, Max pushes the boundaries in sailing manoeuvres, kite handling and board handling.

Max already has a signature move - the slingshot. This is where he approaches the windward mark high (at a closer angle to the wind) to build line tension (the lines of the kite are attached to the harness around his waist) and slingshots (or catapults) around the mark, overtaking a few kiters at one go. Max started it, and now everyone copies it.

SINGAPORE’S SAILING “MACHINERY” KICKS IN

Upon returning to Singapore from that trip where I first met Max, I started triggering our sailing “machinery”.

In 2010, as then president of the Singapore Sailing Federation (SSF), I had launched a long-term strategic blueprint called The Next Leg to develop our pipeline of sailing champions.

The plan aimed for progressive benchmarks, from just qualifying for the Olympics in 2012, to mid-fleet finishes in 2016, top 10 finishes in 2020, and medalling in 2024.

Opportunities arise when new sailing events are first introduced into the Olympic slate, such as the 49erFX, where the pecking order is not as established yet. We identified the 49erFX early as a focus area and campaigned early, and that strategic approach paid dividends at the Tokyo Olympics, with a top 10 finish.

Likewise with kitefoiling in this edition of the Olympics. The Kitesurfing Association of Singapore, whose activities prior to 2019 was limited to recreational kiting, was tasked by SSF to take on high performance functions to support Max and others daring to follow him.

The National Youth Sports Institute, the Singapore Sport Institute (SSI) and the Singapore National Olympic Committee (who sent Max to the World Beach Games in Doha for exposure to multi-sport games formats in 2019) bandied around him, and the SSI placed Max on spexScholarship, the highest tier of support for Singapore’s athletes. The Journey to the 2024 and 2028 Olympics Taskforce took Max under its wing, ensuring a comprehensive and coordinated support system.

In the years that followed, I also kept Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Edwin Tong in the loop about Max's progress.

It was not difficult for me to advocate for Max - his results did all the talking.

These behind-the-scenes insights demonstrate how Max’s Olympic medal was won through deliberate engineering, by him, his parents, and Singapore’s extensive sports ecosystem.

There’s more to come from Max and I hope that Singaporeans are inspired by Max to chart their own paths towards the pinnacle of sports, knowing that Singapore is behind them.

To aspiring athletes, if you have not already done so, take that first step now.

Dr Ben Tan is an Olympian, Asian Games gold medallist and four-time SEA Games gold medallist in sailing. He is also Honorary Advisor and founding Chairman of the Olympic Pathway Taskforce at the Singapore Sailing Federation, Singapore National Olympic Council vice president, Sport Singapore board member, co-chair of the Journey to the 2024 and 2028 Olympics Taskforce and a member of the spexScholarship Selection Committee.