Commentary: Your toilet waste matters more than you think

Every time you flush the toilet, your waste carries valuable pathogen information that can help health authorities detect the spread of diseases early, says Duke-NUS Medical School’s Vincent Pang.

File photo. An NEA officer setting up the autosampler to collect wastewater samples through a manhole. (Photo: National Environment Agency)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Have you ever thought about how your faeces could play a crucial role in preparing for the next pandemic?

Last month, over 200 wastewater and environmental experts from around the world gathered in Singapore for a five-day workshop titled Developing a Regional Agenda for Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance and Research for Epidemics and Pandemics.

Why such a commotion and commitment?

That’s because every time you flush the toilet, the bits and pieces that go down the pipes carry valuable information that can help health authorities detect the spread of diseases early.

WHERE YOUR WASTE GOES

Singapore’s sewerage system has come a long way since the old days when night-soil workers used to go house to house to collect buckets of toilet waste.

By 1997, everyone in the country had access to modern flushing toilets. Today, Singapore boasts a comprehensive sewerage system with advanced wastewater treatment facilities, including the upcoming Deep Tunnel Sewerage System.

But do you know what happens to your wastewater after you flush? Even though we can’t see most of what happens underground, we should never take for granted the ease of sending our wastewater away with just a simple flush.

First, your wastewater travels through the pipes in your home into other underground pipes, eventually leading to public sewers. There are about 3,600km of public sewers and 100,000 sewer manholes in Singapore. Through these sewers, the wastewater makes its way to one of Singapore’s four water reclamation plants.

Wastewater can be collected from manholes either manually or automatically before it reaches the wastewater treatment plant. Hence, wastewater, through these manholes, has gained popularity as a tool for addressing infectious diseases in specific at-risk geographical locations.

Take for example the upcoming Olympics in Paris. Public health experts won’t just be watching the Games, they will also be monitoring wastewater for six pathogens - namely the viruses that causes polio, influenza A, influenza B, mpox, SARS-CoV-2 and measles.

WASTEWATER SURVEILLANCE DURING COVID-19

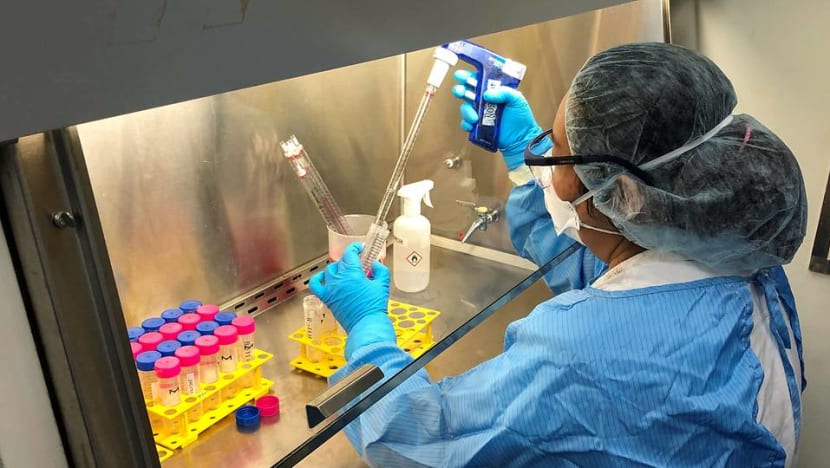

During the COVID-19 pandemic, wastewater surveillance was instrumental in detecting the presence and transmission patterns of SARS-CoV-2 virus and its new variants in Singapore.

By regularly testing wastewater, health experts were able to identify which specific neighbourhoods and dormitories needed more COVID-19 testing.

If virus genetic fragments were detected in the wastewater from one area over a few days, block-wide screening would be triggered and everyone in the area would be tested. Not only did this help identify and isolate infected individuals, it also prevented the virus from spreading further and enabled infected residents to get medical care early to avoid getting severe symptoms.

Regular wastewater testing also helped evaluate how well certain public health interventions - such as isolating COVID-19 cases, vaccination campaigns, and promoting good hygiene and air ventilation practices in places like nursing homes, dormitories and hostels - were working. The baseline signal from regular wastewater testing was used to see if those measures were effective.

Even though the pandemic is behind us, regular wastewater testing remains crucial, especially in these high-risk settings. It helps monitor the transmission risk among vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly or immunocompromised.

FLUSHING OUT OTHER DISEASES

Beyond pandemic management, wastewater surveillance can be used to identify and prevent the spread of diseases such as measles, cholera, typhoid, and polio, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

This has been useful in guiding vaccination strategies and assessing the effectiveness of vaccination campaigns, particularly in polio-endemic countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan. This type of surveillance helps with the early detection of outbreaks, enabling rapid epidemiological investigations, contact tracing, isolation, and infection prevention measures.

Apart from vaccine-preventable diseases, Singapore wastewater sampling today is also used to monitor Zika transmission hotspots. In February, for example, precautionary control measures were stepped up in Boon Lay Place and doctors were alerted to be on the lookout for cases, after persistent virus signals were found in the area.

Similar to dengue, Zika is a virus infection that is spread by the Aedes mosquito. Only about 20 per cent of people infected with Zika display symptoms, and while Zika infection is generally mild, it can cause neurological complications or abnormalities in foetuses. There is currently no specific vaccine or drug against Zika.

Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States is tracking the avian influenza A virus, including its subtype H5N1, in wastewater across 770 sites, amid bird flu outbreaks mainly among the cow herds and poultry farms. Globally, there have been 889 H5N1 cases reported to World Health Organization since 2003 and half of them resulted in death. While there has been no evidence of sustained person-to-person transmission, the World Health Organization has called bird flu an “enormous concern”, urging increased tracking.

KEEPING COMMUNITIES HEALTHY

Compared to nasal swabs, for example, wastewater monitoring is non-invasive and does not rely on testing individuals, thereby complementing traditional healthcare surveillance.

Often, the effectiveness of clinical surveillance relies on a population’s health-seeking behaviour, geographical and financial access to clinics and hospitals. It also depends on how well healthcare organisations can share information with relevant national authorities

But while wastewater surveillance has its advantages, it cannot entirely replace clinical surveillance. It cannot give medical diagnoses nor fully show how many people are sick. Scientists are also still studying ways to use advanced technology to further improve detection of disease from different quality of wastewater and geographical locations.

Wastewater surveillance has the potential not only to prevent future pandemics but also to monitor the health of entire communities. Beyond your flush, many unsung heroes are analysing and ensuring public health is monitored and pandemics are prevented.

As part of an enabling environment, wastewater surveillance programmes need to be understood, supported, and sustained by the community. When the community embraces the benefits of wastewater surveillance, there will then be more motivation for long-term implementation among countries in Asia for pandemic preparedness.

Dr Vincent Pang Junxiong is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Outbreak Preparedness, Duke-NUS Medical School.