commentary Commentary

Commentary: The invisibility of the poor in Crazy Rich Hong Kong

The complexity in measuring poverty in Hong Kong, as well as the social stigma of poverty, often cloak the destitute in obscurity, says one China expert.

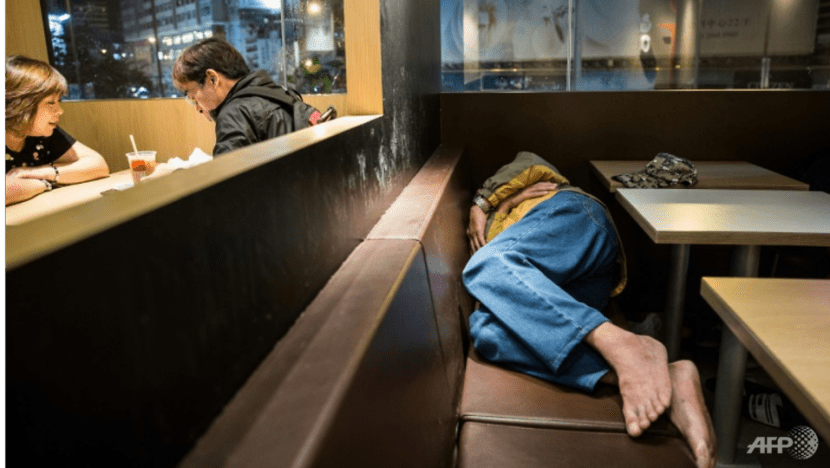

A man sleeps at a McDonalds outlet in the Kowloon district of Hong Kong. (Photo: AFP/Anthony Wallace)

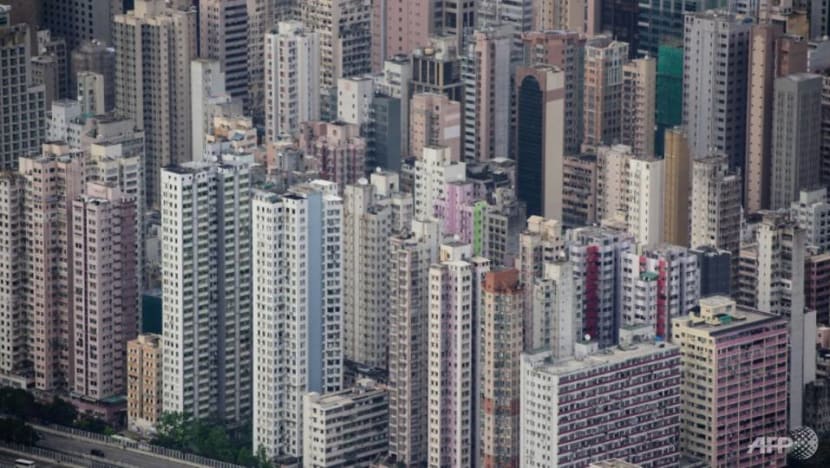

SINGAPORE: Singapore may be the setting of the movie Crazy Rich Asians, but the Asian city that has overtaken New York as the city with the largest population of the “ultra-rich” is Hong Kong.

A research firm finds that with a 31 per cent increase last year, there are now around 10,000 ultra-rich people worth at least US$30 million in Hong Kong, where the number of billionaires has also grown remarkably by almost one-third in 2017.

The former British colony is now second to New York with 93 billionaires, whereas Singapore takes the 7th spot with 44 billionaires.

In this age of the Internet and the social media, it is probably not an exaggeration to say that at no point in history have the rich and their riches been so visible.

The young and well-heeled have taken to flaunting their lavish lifestyle on Instagram; the who’s who of the world’s top billionaires are revealed in Forbes’ annual ranking; there is even a Bloomberg Billionaires Index of the world’s 500 richest people that is updated on a daily basis.

READ: Once the Pearl of the Orient, Hong Kong poised to regain its shine, a commentary

Whereas identifying and ranking the rich according to their net worth seem quite straightforward, the same cannot be said of the poor.

“How poor is poor” in any society is often debatable.

In assessing the poverty situation, policymakers and experts argue about the pertinence of absolute versus relative poverty, the income approach versus the deprivation approach and so forth. Many governments are loath to set a poverty line.

The complexity in measuring poverty, as well as the social stigma of poverty, often cloak the destitute in obscurity.

That is to say, while many of us would be able to name real estate magnates Li Ka-shing or Lee Shau-kee as the richest men in Hong Kong, most of us know very little about the poor in one of the world’s most expensive cities.

READ: Behind the brain drain in Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan, stymied aspirations and growing rootlessness, a commentary

WHO ARE THE POOR?

In 2013, the Hong Kong government drew its first official poverty line at half the city’s median household income. Those who fall below it are considered poor.

Based on the 2016 Hong Kong Poverty Situation report, Hong Kong has a poverty rate of almost 20 per cent, with 1.35 million of the city’s 7.35 million residents living below the official poverty line.

Another study also shows that more than 40 per cent of low-income Hong Kong households or around 71,000 people spend an average of less than HK$15 (US$1.92) on each meal, in order to cope with the city’s astronomical rents.

The amount converts to a meagre S$2.60, which cannot even buy you a meal at a Singapore hawker centre nowadays.

You may also have read about the growing number of “McSleepers” or the “McRefugees” who spend their nights in McDonald’s outlets in Hong Kong.

But you would be wrong to jump to the conclusion that these are the homeless and the unemployed.

More than half of the McSleepers were actually employed, and 71 per cent of them either owned or rented flats.

READ: This is what the face of poverty looks like in Singapore, a commentary

Rising rents and poor living conditions, however, had impoverished and driven these people to seek sanctuary in the city’s fast food outlets instead.

In Hong Kong, 91,787 households live in sub-divided units, which are residential units split into two or more living quarters. For an average per capita floor area of 5.8 sq m, 83 per cent of these households pay a monthly rent ranging from HK$3,000 to more than HK$6,000.

The working poor is an often overlooked group among the destitute, who are commonly stigmatised and seen as lazy.

Yet research using the 2011 Hong Kong Population Census has found that low-paid work is one of the key factors leading to in-work poverty.

Even with a statutory minimum wage introduced in 2011 and adjusted every two years, a worker can hardly afford a meal at McDonald’s with his hourly pay.

With effect from 1 May 2017, the hourly minimum wage has been raised from HK$32.50 to HK$34.50 (which works out to S$6).

A Big Mac meal at McDonald’s costs about HK$36.

The two-yearly adjustment of a miserable HK$2 led Hong Kong low-paid workers to mock the government for giving them subsidies for soy sauce.

Among the various age groups of Hong Kong people living in poverty in 2016, the proportion of the elderly poor aged 65 and above was the highest at 44.8 per cent.

In comparison, the poverty rates of those aged 18 to 64 and those under 18 were 13.6 per cent and 23 per cent respectively.

Even after recurrent policy interventions, there were still 337,400 elderly poor in Hong Kong at a poverty rate of 31.6 per cent.

Although the increasing number of working elders since 2009 has been associated with a lower poverty rate vis-à-vis that of the non-working elderly, it is unrealistic to expect the old to keep working beyond a certain age.

DRIVEN TO LIVE ELSEWHERE

The high cost of living in Hong Kong has driven some of its elderly residents to relocate to mainland China.

As of 2017, an estimated 14,600 Hong Kong elderly aged 65 or above have applied to claim their Old Age Allowance from the Hong Kong government while residing in Guangdong.

More have also been forced to relocate farther inland beyond Guangdong as the cost of living rises in coastal China.

Children aged 17 and below in single-parent households and new-arrival households — that have at least one member from mainland China who has resided in Hong Kong for less than seven years – are also more likely to experience destitution.

The 2016 Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report showed that the poverty rates of single-parent and new-arrival households after policy intervention were more than double the overall rate.

This is chiefly because most of these poor households had to support more children while having only one working member, in comparison to other poor households in Hong Kong.

Despite Hong Kong’s sustained economic development over the past three decades, the economic status of single-parent families has not improved much, exposing the children in these disadvantaged families to a greater risk of intergenerational poverty.

THE RICH-POOR DIVIDE IS HARMFUL

Amidst an ageing population, smaller household sizes and a widening gap in the rates of pay increase between low-skilled and highly-skilled workers, Hong Kong’s Gini coefficient rose to 0.539 in 2016. The post-tax and post-social transfer Gini coefficient was 0.473.

The richest 10 per cent of households earned close to 44 times more than the poorest 10 per cent, a rich-poor gap that is remarkably high for a developed economy.

Some believe that the wealth gap has contributed to Hong Kong’s political polarisation.

READ: A commentary on Hong Kong's cautionary tale for Singapore

A study, for example, reveals how the rich tend to be less generous and collaborative when they know that their neighbours are less well-off than them.

Research also finds that when we mix selectively with people of a similar social status, the lack of interaction with other social groups undermines our ability to empathise with others and to trust them.

This may explain, for instance, why Hong Kong lawmakers representing the business interests had opposed to and held back the introduction of a statutory minimum wage for a decade before its final passage in the legislature.

Ultimately, greater inequality benefits no one over the long run: The unrealised potential of the lower income group is a loss to the economy as a whole, and the growing distance between the rich and the poor stifles GDP growth.

Dr Yew Chiew Ping is head of the Contemporary China Studies Minor at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.