Commentary: Why are these PSLE maths questions so hard?

The big stressor of COVID-19, a natural focus on PSLE’s sorting role and investments in tuition combine to make PSLE maths papers a flashpoint each year, says NIE’s Jason Tan.

Examination venue for students on quarantine. (Photo: Ministry of Education)

SINGAPORE: This year’s Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) mathematics papers have been at the centre of controversy over the past few days.

Parents have reportedly claimed their children have burst into tears over the perceived toughness of the papers. Media stories speak of some students also requiring emotional support from school counsellors.

These complaints, some of which have been posted on Education Minister Chan Chun Sing’s Facebook page, have focused on the needless stress on students amid challenging times.

So widely talked about was this PSLE examination angst that local blogger Lee Kin Mun, popularly known as mrbrown, produced a video offering advice and urging students to remember their PSLE grades do not represent the totality of who they are as individuals, and that their parents love them unconditionally.

BIG STRESSES SINCE COVID-19 HIT

Why are these PSLE mathematics questions so hard?

We’re naturally inclined to feel huge empathy towards our 12-year-olds after a coronavirus-sized disruption over the past two years.

Students have had to cope with intermittent school closures and the imposition of home-based learning (HBL) since 2020.

Then there is also the stress brought about by the curtailment of co-curricular activities and restrictions imposed on recess and other socialisation opportunities within schools and between households.

Students have also had to prepare themselves for the uncertainties associated with being the pioneer cohort for the revised PSLE scoring system.

The Ministry of Education (MOE) has publicly acknowledged that HBL is not an adequate substitute for the depth and variety of learning experiences students enjoy by being physically present in school.

And in recognising the impact of HBL imposed over the past two years and to support the wellbeing of students, MOE removed what it terms “common last topics” from both last year’s and this year’s PSLE mathematics and science.

Deputy Director-General of Education (Curriculum) Sng Chern Wei also took pains to assure parents in a forum letter over the weekend that MOE would take these disruptions into account to ensure that students would not be “disadvantaged by these exceptional circumstances”.

SHIFTS IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM TO NURTURE LOVE OF LEARNING

Why have some parents and students experienced such distress? And why despite MOE’s attempts over the past decade to reduce stress levels and nurture what it terms “the joy of learning” in students?

Related:

Then Education Minister Ong Ye Kung had acknowledged back in 2018 the risk of schooling becoming overly stressful.

For that reason, beginning in 2019, all weighted assessments in Primary 1 and 2 were scrapped, with Primary 3 and 5 mid-year exams following suit in subsequent years.

In a similar vein, the revamped PSLE scoring system was touted as contributing to reducing the over-emphasis on academic achievement by reducing fine differentiation and eliminating peer comparisons of scores.

Yet, the fact that this year’s PSLE mathematics papers have yet again been a lightning rod for anxieties testifies to the practical difficulties in securing a match between MOE’s official policy goals on the one hand, and parents’ and students’ perceptions and behaviour on the other.

NATURAL FOCUS ON PSLE’S SORTING MECHANISM

Perhaps the reality for many parents and students is that PSLE remains a high-stakes examination that determines students’ chances for secondary school admission, notwithstanding recent reforms to the educational system.

In many ways, this year’s parental concerns over the PSLE maths papers are not new.

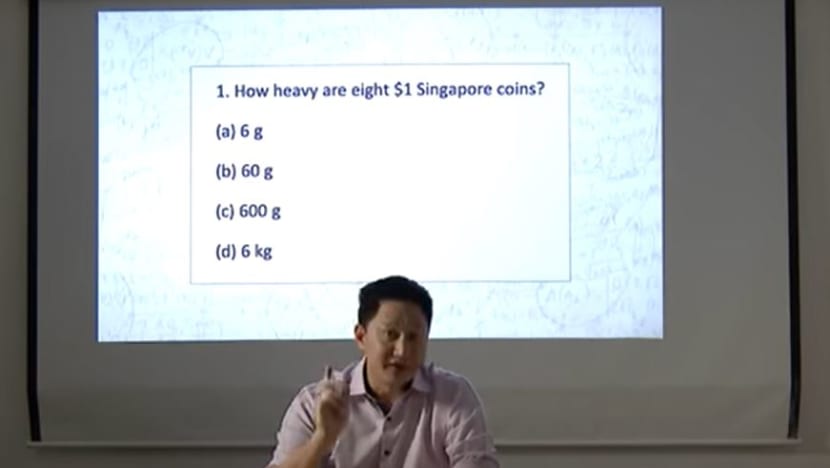

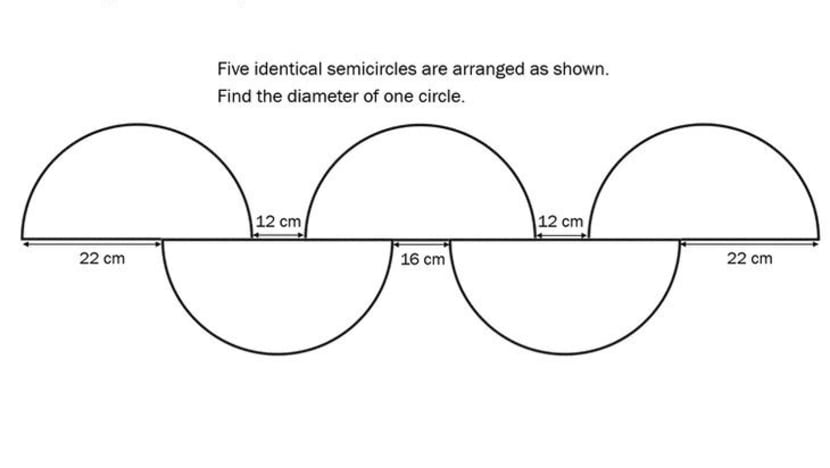

Similar anxieties had surfaced in previous years, like when in 2015, some parents took issue with a question that asked students to estimate the weight of eight one-dollar coins, and again in 2019 when a question about circles and distances got many scratching their heads.

The diagnostic element inherent in the PSLE understandably tends to be overlooked as many parents and students naturally focus instead on the powerful selection and sorting mechanism the PSLE represents.

Most invest a considerable degree of money, time and energy in exam preparation, welcoming moves like the Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board (SEAB) publishing PSLE examination papers since 1993 in a bid to acquaint parents and students with the examination format as well as expected standards.

The ubiquity of the private tutoring industry is both evidence and accelerant of the parental anxiety surrounding the PSLE.

By the time students sit for exams, most have gone through countless hours of revision and practice. The subsequent disappointment some feel when encountering questions they are unable to answer is then all the greater.

It can be difficult to come to terms with the reality that an exam like the PSLE, which serves as a means of differentiating among students, needs to have a system of setting examination papers lending themselves to this purpose.

Even so, the SEAB has attempted to clarify over the last decade that exam papers have a range of questions – easy, average and more challenging – to cater to students with a wide range of abilities and maintain comparability of standards from year to year, with robust processes ensuring coherence between the exam, syllabus objectives and learning outcomes.

Listen to three working adults reveal how their PSLE results have shaped their life journeys in a no-holds barred conversation on CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast:

These worries remain despite MOE Curriculum Planning and Development’s public emphasis on the development of “thinking, reasoning, communication, application and metacognitive skills through a mathematical approach to problem-solving” in addition to the acquisition of mathematical concepts for everyday use and continuous learning.

The last thing anybody wants is for students to lose confidence in learning mathematics or to hate learning the subject because of their disappointment with the PSLE mathematics exams.

It would be regrettable if these larger aims were to be lost amid a public focus on the perceived toughness of some examination questions, even if they were designed precisely with the intention of sieving out top candidates.

But as long as the PSLE continues to play this role of determining a student’s subsequent educational pathways, it is unlikely these sorts of complaints that have emerged this year will disappear.

A caveat is that less is known about how widespread these worries are when parents and students who might not feel similarly high levels of anxiety do not have their views widely highlighted.

But the irony is how such a controversy over mathematical assessment at the end of primary schooling continues locally when Singapore’s primary mathematics curriculum has been long been admired as a model producing top-ranked students in global comparisons and adopted by schools in other countries such as the UK and the US.

For now, the advice from mrbrown for all students and parents to remember PSLE is not the be all and end all seems prescient.

Jason Tan is an associate professor at the National Institute of Education.