China’s small cities defy housing slump as young buyers seek affordability

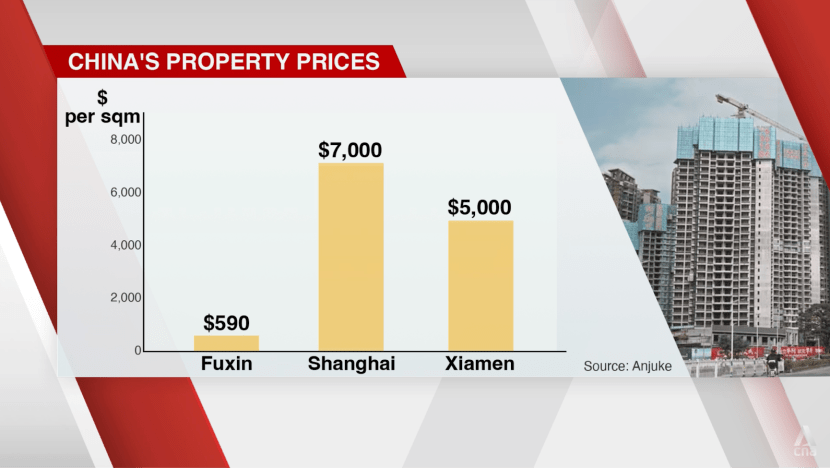

Secondhand flats in fourth-tier city Fuxin cost an average of about US$590 per sqm, compared with around US$7,000 per sqm in first-tier city Shanghai, according to a real estate platform.

Unhurried streets and shops that shutter by sundown. Life moves at a gentler pace in Fuxin, a city tucked away in the northeast or China’s so-called Rust Belt, just a two-and-a-half-hour train ride from Beijing. (Photo: Tan Peng Guan/CNA)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

FUXIN: Unhurried streets and shops that shutter by sundown.

Life moves at a gentler pace in Fuxin, a city tucked away in the northeast of China’s so-called “Rust Belt”, just a two-and-a-half-hour train ride from Beijing.

Yet, in this former mining hub’s quiet corners, a growing community of young newcomers is breathing new life into its streets, drawn from across the country in search of something different.

Among them is 29-year-old Xiao Du, who moved from over a thousand kilometres away from Luoyang, a city in Henan province in Central China.

She bought her 28qm flat for just under US$3,500 in 2024, from online secondhand marketplace Xianyu.

“The housing prices there are really cheap. If you’re looking for a place to live, it’s a good option,” she told CNA.

But she warns that a higher standard of living comes with a higher price tag.

“At this price, you can basically only buy a top-floor unit there, which is more prone to water leakage and is in an unfinished condition. So I feel that people might have a misconception about its low housing price,” she added.

AS CHEAP AS "CABBAGES"

Housing prices such as those in Fuxin have gone viral on Chinese social media, with many netizens describing rock-bottom property prices as being as cheap as “cabbages".

According to data from Anjuke, one of China’s largest real estate platforms, secondhand flats in fourth-tier city Fuxin cost an average of about US$590 per sqm. That is compared with an average of US$7,000 per sqm in first-tier city Shanghai, and about US$5,000 per sqm in third-tier city Xiamen.

Fuxin is also known for its relatively cheaper cost of living. A common feature in social media videos about life there are the city’s morning markets, where vloggers flaunt their grocery bargains.

When CNA visited the Fuxin Power Plant Morning Market, around three dozen stalls lined the area, offering essentials ranging from fresh meat to pickles.

With 10 Chinese yuan (US$1.30), shoppers could walk away with five apples or 10 cabbages.

CATCHING THE EYES OF YOUNG PEOPLE

Fuxin is among a handful of fourth-tier Chinese cities that have caught the eyes of those seeking respite from the pressures of modern life on a limited budget, including Hegang further up north and Hebi in central China.

Coupled with their low cost of living, these cities offer a viable option for those with modest savings to build a new life or to simply “tang ping” (lie flat in English), a mindset where people reject the pressure to achieve traditional success.

There are many reasons young people choose to move to these cities, according to Fuxin resident Ms Du.

“Some are due to sexual orientation, while others are because of work. A lot of it actually comes down to job-related factors," she said.

"Some people move to Beijing for work, while others simply can’t afford to buy a home in their own city after many years. Family circumstances also play a big role."

For Ms Du, owning a home has given her a newfound sense of freedom, in a culture where women have traditionally depended on family or male partners for financial security.

BUCKING THE TREND

For decades, the development of China’s old industrial base, like Liaoning province where Fuxin is located, lagged behind other regions.

The housing crisis hit the region especially hard, unlike cities with stronger appeal, said Professor Lan Deng from the University of Michigan's Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

“Their population has been shrinking, and the jobs have also declined. So now, you build a lot of housing, and then you have a much larger housing stock than what you know your population or economic opportunities can absorb,” she said.

In recent years, efforts to revive the local economy began to pay off. Last year, Liaoning logged gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 5.1 per cent, beating the national average.

In 2023, the province saw net population growth for the first time in more than a decade, with a net inflow of 86,000 people.

According to Fuxin real estate agent Xiao Zhang, the city’s location also plays a part.

“With transportation options so convenient, the distance to another city becomes very short,” said Mr Zhang, who works at real estate firm Fu Jia Fang Chan.

“People might say they can earn money from there and then look for a place not too far from their capabilities. In this case, they might be able to rent a place outside the city or even the company-provided accommodation,” he adds.

“However, if they live in a more prosperous city with higher wages, they still face the reality of higher living expenses and greater pressure right?”

Still, the influx of young people from outside Fuxin has stirred mixed feelings among its residents.

One resident told CNA that “a larger population helps a city develop further”, while another highlighted that “it could also drive up property prices, making it more expensive for locals to buy".

AFFORDABILITY AS A DEFINING FACTOR

Yet, the shift toward lower-tier cities reflects a deeper change – one where affordability is becoming a key factor in how young people decide where to live.

Young people are also snapping up older, smaller and dilapidated houses in first-tier cities like Beijing.

This trend contrasts with the Chinese government’s push for higher-quality housing, which it defines as “safe, comfortable, eco-friendly and smart”, according to the government work report unveiled during this year’s Two Sessions.

That is on top of earlier pledges to expand subsidised housing to meet the needs of young buyers. Presented by the housing ministry late last year, it is courting the younger crowd in a bid to improve housing demand and stabilise China’s real estate market.

Still, analysts believe there are other factors at play including job and educational opportunities, or even the lack of.

Associate Professor Laura Wu from Nanyang Technological University’s School of Social Sciences noted that difficulties finding a job in big cities can also drive people to smaller ones.

“But if this is going to happen at a large scale, I’m sure it’s something the Chinese government is going to monitor very closely,” she said.

“Because after all, I think this is to a large extent, a waste of talent … If they have a better job opportunity, they could make good use of their education and human capital rather than just ‘tang ping'.”