'Like being served a sentence': Youth discontent flares as China puts renewed work into raising retirement age

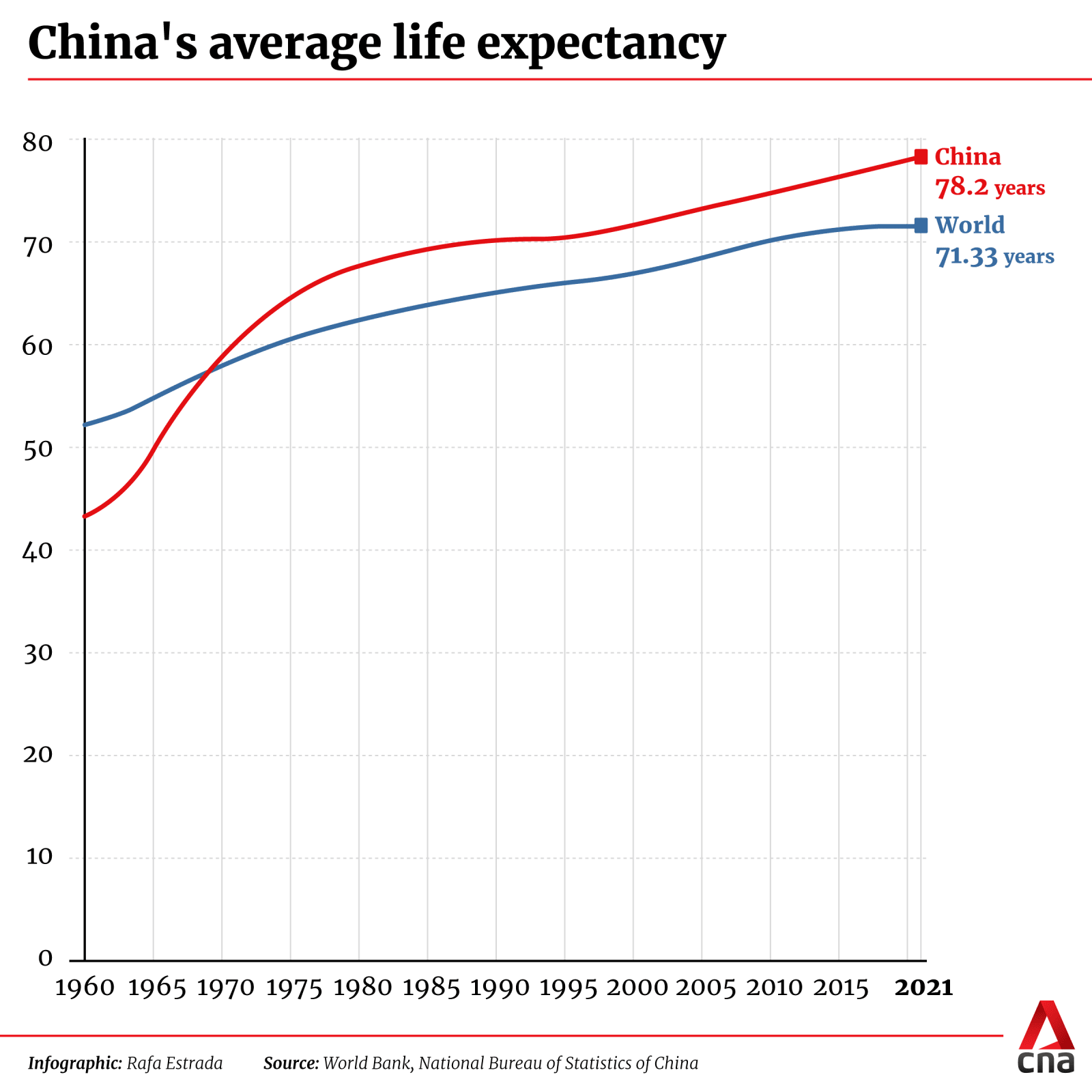

Set in the 1950s, China’s retirement age was a product of the times - when life expectancies were shorter and conditions were vastly different. Fast forward to now and a recalibration appears firmly on the cards, but analysts warn that the government needs to move carefully lest unhappiness over the move boils over.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When Ms Jasmine Chen first heard that China was making a fresh push to raise the retirement age, her initial response was unlike many of her peers.

“I’m not angry,” the 36-year-old Shanghai native who works as a financial analyst at a Chinese e-commerce platform told CNA.

“I've always been optimistic, and I believe there's always opportunity in a crisis … this is the point in time that has forced me to think ahead about retirement,” she added.

At 36, Ms Chen sits squarely in the centre of China’s working-age population - defined as between 16 and 59 - which at about 61 per cent makes up close to two-thirds of the country’s 1.4 billion people, according to official data.

But that number is set to shrink rapidly as a fast-ageing population, longer life expectancies, and a plummeting birth rate bite.

Coupling this with one of the lowest statutory retirement ages in the world, it essentially means more elderly Chinese dipping into a dwindling pension pot - spelling stark economic implications not just for the world’s second-largest economy, but potentially the wider region as well.

Analysts point out the growing concern from the Chinese leadership, evidenced by the outcomes of a recent reform-focused meeting of China’s Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee.

Among the raft of pledges was one stating that reforms would be advanced to gradually raise the retirement age, as laid out in the resolution document of the third plenum.

The pronouncement has received fierce backlash online - particularly from young people. Still, observers that CNA spoke to say raising the retirement age is more necessary for China now than ever.

Dr Xiujian Peng, senior research fellow with the Centre of Policy Studies at Victoria University in Australia, warned that if action isn’t taken now, “(the government) may not have enough (of a) window of opportunity to increase it when the time comes, and ageing will become a very serious problem”.

WORKING TOWARDS LATER RETIREMENT

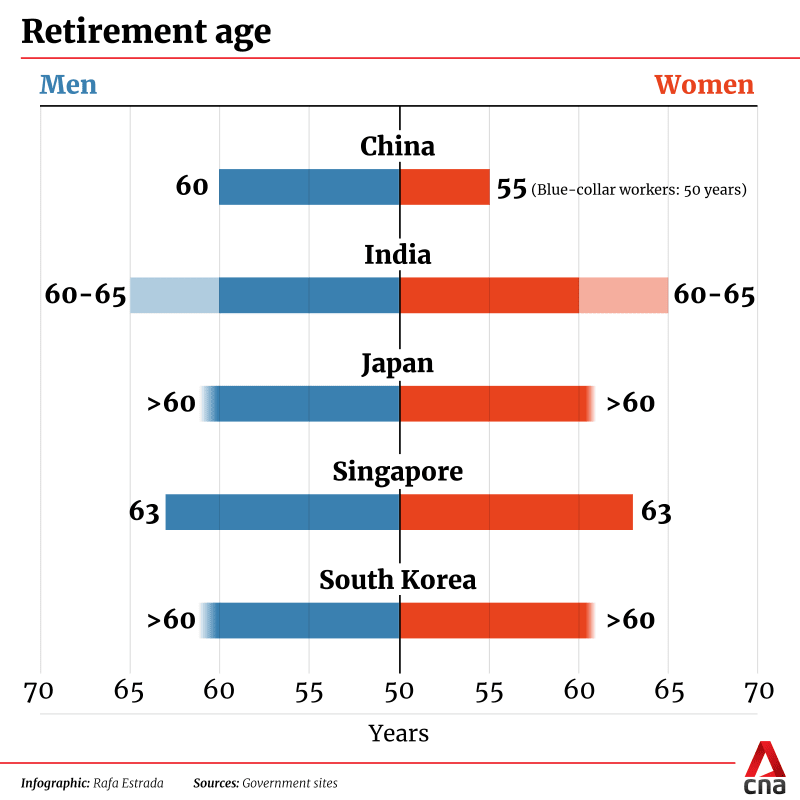

China has one of the lowest retirement ages in the world.

It’s set at 60 for men, while for women it’s 55 for white-collar workers and 50 for the working class. In comparison, the average for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in 2022 was 64.4 years for men and 63.1 for women.

China’s retirement ages were established in the 1950s when the national life expectancy was shorter and hovering below 50. The average life expectancy rate has skyrocketed since, hitting 78.2 as of 2021, higher than the United States, and is projected to exceed 80 years by 2050, according to a 2023 report by international medical journal The Lancet.

Through the years, the country’s retirement ages have stayed the same. One consequence has been the growing strain on the pension system as the workforce shrinks and payouts are made to more retirees.

Against this backdrop, China watchers have singled out the mention of raising the retirement age in the recently concluded third plenum, as a signal that Beijing is taking action to arrest the trend.

“In line with the principle of voluntary participation with appropriate flexibility, we will advance reform to gradually raise the statutory retirement age in a prudent and orderly manner,” stated the resolution document, without specifying any implementation details.

China has indicated a deadline, stating that all 300-odd reform tasks in the document should be completed by the time the People’s Republic of China marks its 80th anniversary in 2029.

While the document did not specify what the retirement age would be revised to, hints have previously emerged. A report published in December by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a leading state-run think tank, estimated that everyone would eventually retire at 65.

Mr Huang Tianlei, research fellow and China programme coordinator at Peterson Institute for International Economics, told CNA it suggests the government is “making a compromise”.

“It's basically letting people decide if they want to retire later. If they do decide to retire later, they will probably receive a higher pension; and if they decide to receive (the pension) on time or even early, they will get less,” he said.

“It’s to provide an incentive of sorts for people to retire a bit later.”

RILING UP THE YOUTHS

The plans have struck a nerve in the country - particularly among young people, with many expressing unhappiness online.

“Those who want to retire are those working in miserable conditions, and those who don’t want to retire are working in high-paying jobs while doing much less. How can young people live?” lamented one user on Chinese social media platform Weibo.

Another had concerns about job security. “As long as the government creates a good working environment for the ordinary people, we are all willing to work for a few more years, and earn our own keep without letting our children worry too much.

But the question is, can a person in his 50s or 60s find something to do in this era of involution?”

Ms Chen, the financial analyst, is similarly concerned, citing “challenging” prospects due to factors like the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and the possible displacement of jobs.

She is mulling multiple backup plans instead of relying on one job.

“We have to adapt to change. I am thinking of starting first by investing and then upgrading my skills. Or I could take on a coaching role to help others pass the certified public accountant exams,” she told CNA.

Referring to the likelihood of later retirement, 24-year-old logistics supervisor Woody Zhu told CNA it feels like he is being served a “sentence”.

“I'd say even if it's voluntary, maybe at most 10 per cent would actually do that on their own will,” he said.

Mr Zhu pointed out how many of his friends have turned to humour to channel their frustrations, and one way is through the sharing of memes on WeChat.

“PEOPLE MUST ACCEPT THIS PEACEFULLY”

Mr Huang feels that the uproar among youths is “understandable”.

“Many young people are struggling to find work. Keeping older people in the market will inevitably mean fewer opportunities for younger people who are desperately looking for jobs,” he said.

“My guess is that the policy will continue to face huge obstacles from the people and may not become a reality anytime soon. Even if it becomes actual policy, people may not be as responsive as the government expects them to be,” he added.

The national jobless rate for the 16-24 age group - excluding students - was at 13.2 per cent last month, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, which noted that it was the third straight month of improvement.

But that’s against a sharper-than-expected growth slowdown in the second quarter of this year.

Beijing has also been under pressure to create more jobs, with more than 11.7 million new university graduates set to enter the labour market this year.

Victoria University’s Dr Peng said while the latest push by China to raise the longstanding retirement age sends a “very positive signal”, she cautioned that the issue remains very sensitive, highlighting it as a reason why the government has hesitated to do so for “many, many years”.

China raised the prospect of raising retirement ages as far back as 2013. Then, a report by the state-run Global Times quoted officials as saying it would be done “in progressive steps”. Also, that the public would be notified “a few years prior to the actual implementation”.

More recently in 2021, Chinese authorities said they would delay the legal retirement age over the next five years, but offered no further details.

“This reform is not as easy and is very complicated. The government needs to consider all the people's thinking and prevent any potential trouble. People will need to accept this peacefully,” said Dr Peng.

She brought up what happened in France as an example. Early last year, a government proposal to increase the retirement age to 64 from 62 sparked nationwide protests, paralysing public transport and municipal services.

Heaps of garbage in the streets of the capital Paris became a protest symbol. Despite vehement opposition, the reforms were eventually pushed through by French President Emmanuel Macron.

Dr Peng referred to Australia’s model as one that China could potentially take notes from. Australia does not have a set retirement age. Rather, citizens can get access to their pension upon hitting a stipulated age, which was raised to 67 from 65 last year.

“(Australia) also said they would do this gradually, and based on the people’s willingness.

“In Australian universities, if the professors would like to stay on for longer, they can, and not be forced to retire. I believe China can learn from this,” Dr Peng said, highlighting that her PhD supervisor is still working at the age of 78 - for six days a week, no less.

Here in Southeast Asia, countries are also taking action as the region faces the tough challenge of a fast-greying population.

Since 2021, Vietnam has been gradually raising its retirement ages, targeting 62 for men and 60 for women. Meanwhile, Singapore’s retirement age will go up by one year to 64 in 2026, as part of a progressive approach to raise it to 65 by 2030.

PENSIVE OVER PENSIONS

Online critics of a potential raising of the retirement age have also brought up the prospect of delayed access to their pensions.

While analysts point out that details are vague, with no specifics about implementation, they note that raising the retirement age would go some way in taking some heat off China’s buckling pension system.

“Because (China has) a fast-ageing population, the pension fund could run a deficit and the deficit will grow larger with the current pension system. This will put a high pressure on the government. This is not sustainable,” said Dr Peng.

State-run think tank the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences said in 2019 that the country’s main state pension fund would run dry by 2035. The estimate came before the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacted a heavy toll on China’s economy.

Raising the retirement age would mean that fewer people can dip into the pension pot while simultaneously having more worker contributions, Dr Peng pointed out.

“It’s good for the sustainability of the pension system, reducing the financial pressure on the government.”

Even so, not all analysts are convinced that raising the retirement age will be a game changer as they pointed out the raft of challenges confronting the world’s second-largest economy.

While Dr Peng believes it will be a “very effective policy” over the short to medium term, she noted that for the longer term, “the government must increase the fertility (rate), to work hand-in-hand with this move.”

Referring to the recent third plenum, Mr Huang pointed out that the resolution document is “very much focused on tech, self-sufficiency, indigenous technology, supply chain resilience and national security”, which he believes is “just the wrong approach”.

“It does not seem to place households, employment front and centre, and that, frankly, should be the strategy of the Chinese state in dealing with its current economic challenges.”

Mr Huang also noted that China, like other major economies such as the United States, is entering the age of AI, something he believes the country is not prepared for as the technology replaces “a lot of jobs”, and lower-skilled workers could potentially get pushed out.

“Among all policy options, if you think of the cost-benefit analysis, I don't think (raising the retirement age) is the most effective solution to deal with the slowing economy,” he said.

“Maybe they want to put this out and see how the public will respond, and if the public doesn't like it, they'll just forget about it.”

Regardless of what’s decided at the top, Ms Chen and Mr Zhu are focused on best playing with the cards they’re dealt - later retirement or not.

“Everyone should start having their own plans for their futures now,” said Ms Chen.

As for Mr Zhu, he’s taking a sanguine view of the road ahead.

“If I can't find any decent job, I can just teach guitar as a part-time job to survive…(but) my company currently supports me, and I think I can sustain a steady career for as long as I want,” said the 24-year-old.

“In China, we have such fierce competition, and as a rather young guy, I accept that, because having a job matters more than the stress that comes with it. So I’m now working with my 120 per cent effort.”

His father, just one year shy of the retirement age, has these words for him: “Break a leg, young man, the future is yours.”