Wrinkles, workouts and wisdom: China’s ‘silver-haired bloggers’ rewrite what it means to age

From gym workouts and fashion tips to reflections on ageing, China’s “silver-haired bloggers” are gaining loyal followings with candid, unpolished glimpses of later life.

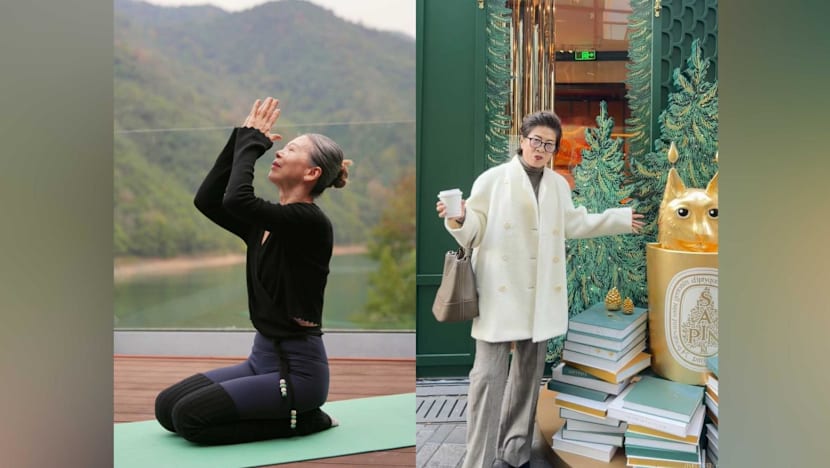

Ping Bao (left) and Grandma Xixi (right) are among a growing number of Chinese seniors who are not just using social media but also creating and sharing content on these platforms. (Photos: Xiaohongshu/hipingbao, Grandma Xixi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: From lifting weights at the gym to practising yoga, Ping Bao regularly documents her fitness routine online.

The Shanghai-based vlogger also shares recipes for healthy meals and styling tips for outfits of the day.

Such content is more often associated with much younger creators. But at 64, Ping embraces her age openly.

“Turning 64 doesn’t mean life is over, my wrinkles and white hair are my badges of honour,” she said in a 2025 wrap-up video posted on Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu.

With her lively and cheerful presence, Ping has amassed more than 180,000 followers on the platform since she began vlogging three years ago.

Ping is far from alone. Across China, a growing number of seniors aged 60 and above are moving beyond social media consumption to content creation, a shift unfolding as the country grapples with a rapidly ageing population.

An enjoyment of sharing with like-minded people, coupled with the ease of using Chinese social media apps, are reasons why more seniors are doing so, say analysts.

“SILVER-HAIRED BLOGGERS”

Known locally as “yin fa bo zhu”, meaning “silver-haired bloggers”, analysts point to the raw, unvarnished nature of their content as a major draw.

“By simply being themselves, such as sharing hobbies, life lessons, or everyday joy, they offer a refreshing contrast to highly produced influencer content,” said Shi Cheng, a professor focusing on ageing and social policy at Lingnan University in Hong Kong.

“Their unique perspectives on history, culture, and resilience also provide meaningful connections across generations.”

State news agency Xinhua, citing data from Xiaohongshu, reported that the platform had more than 30 million monthly active users aged 60 and above by the end of 2024. The number of senior content creators on the platform has also tripled over the past two years.

Meanwhile, a report by Douyin showed that in 2023, around 23 million videos were created daily by users aged 50 and above.

Like Ping, another retiree has also gained a sizeable following on Xiaohongshu.

The 68-year-old, who goes by the handle “Grandma Xixi”, shares fashion and travel content alongside snippets of her daily life caring for her grandchild. She also posts photos of her outfits of the day and documents how she keeps her blood sugar levels in check.

“I’m turning 69 this year, going from a retired granny taking care of young children to becoming an elderly fashion blogger,” she wrote in a post on Jan 15.

“In my younger years, I was often busy with work and taking care of my children, so I never knew how to take initiative and learn new things. It’s only when you’re old that you realise you have to keep learning or your daily life won’t be good!”

Xixi said she began posting on Xiaohongshu about two years ago, describing the platform as a way for her to learn new things, travel more widely and form meaningful connections through her content.

“It has enriched my life. And I would also want to thank my over 50,000 fans and friends. Despite my age, I am still full of positive energy.”

Nobel Prize-winning author Mo Yan, 70, has also made his mark on Chinese social media, with his reflections and vlogs finding a combined following of more than 4.8 million on Xiaohongshu and Douyin.

"I feel that mobile phones have become our diaries. Not only can you pen your thoughts down (on your phone), you can also (use it) to take photos and videos. So I suppose it has become a digital diary,” he said in a video posted on Xiaohongshu on Dec 28 last year.

CROSS-GENERATIONAL APPEAL

Content from older creators is often perceived as more authentic than that produced by younger counterparts, analysts said.

“They often offer unfiltered life lessons which foster cross-generation nostalgia and admiration,” Lai Ming Yii, a strategy manager at market research firm Daxue Consulting, told CNA.

“Humour is used as a universal draw, whilst younger influencers are more polished and focus on trends,” she added.

Senior creators often draw loyal older fans from lower-tier cities in China, Lai noted.

At the same time, Shi from Lingnan University noted that their content also appeals to younger audiences.

“Unlike younger influencers, senior creators often focus on traditional skills, life reflections and graceful ageing,” she said.

In her 2025 wrap-up video, Ping recounted how being a vlogger led her to resume the practice of daily planning and reflections, which she had cultivated during her schooling and working years.

“I thought that when I retired, I would finally be free from writing these things,” she said, describing how she had fallen into a cycle of setting goals that went unfulfilled, followed by self-blame and anxiety.

“But I didn’t feel a shred of happiness. Instead, I felt like my life had lost its direction,” said Ping, describing her days as “drifting aimlessly”.

“For 10 years without summaries or plans, until my 60s, when I became a blogger and picked up this rhythm again.”

Ping further shared how she fronted a livestream for the first time last year.

“My heart was in my throat, my voice wouldn’t stop trembling,” she said. “But for me, it was already a huge breakthrough, stepping out of my comfort zone.”

Her reflections have drawn an outpouring of supportive comments online, including from younger people who said they find her outlook inspiring.

“I hope that when I’m in my 60s, I can be like (Ping Bao) jiejie,” one Xiaohongshu user, Xiao Yu, commented.

“I’m 25 at the moment and I don’t want to get married; I just want to do what I love.”

For vloggers such as Ping and Xixi, encouragement from their own children played a role in their decision to begin posting content online.

DIGITAL EXCLUSION TO ADAPTATION

Analysts said that for many older users, the move into content creation was a natural extension of habits they had already developed online.

Shi from Lingnan University observed that initially, the seniors simply wanted to document their own lives and to find some enjoyment.

“For example, WeChat has a ‘Moments’ function, and I know many elderly people love posting there,” Shi said.

WeChat’s “Moments” operates as a personal social feed, where users can share photos, short videos and daily updates.

“But (WeChat’s) ‘Moments’ function is only visible to (the user’s) friends,” Shi pointed out.

“However, on platforms such as Xiaohongshu or Douyin, you can reach a wider audience. A lot of (older) people started with this mindset of sharing their daily lives, and gradually they find out that many other people actually enjoy watching what they are doing.”

Unlike in past decades, where the vast majority of Chinese seniors were effectively “digitally excluded”, the average older person today has become a “digital migrant”, with smartphone ownership now “near-ubiquitous”, said Shi.

According to a July 2025 report from the China Internet Network Information Center, China has 160 million internet users aged 60 and above, meaning roughly one in two seniors in the country is online.

“WeChat becomes their central hub for socialising, mobile payments, and video calls, while platforms like Douyin and (short-video app) Kuaishou dominate their entertainment.”

This digital shift, Shi said, has granted them “unprecedented” independence, reshaped their consumption patterns and created new social bonds through online communities.

“The barrier to entry isn’t that high anymore, because it’s already woven into (older people’s) daily habits, so accepting it becomes much easier,” Shi said.

Businesses are taking growing notice, said analysts.

“Douyin and Kuaishou are increasingly targeting elderly people through entertaining short videos and grassroots content through ‘silver-haired’ creators,” said Lai from Daxue Consulting.

The trend has also spurred the rise of platforms built specifically for older users, as companies bank on China’s growing “silver economy” - “yin fa jing ji” in Chinese - that essentially refers to products and services catering to the ageing population.

One example is Hongsong. Founded in 2020 to “create a wonderful retirement life”, it positions itself as a senior-focused app offering interest-based learning, social interaction and lifestyle services.

Hongsong has amassed more than 10 million registered users, making it the “largest vertical interest-based social platform” for retirees in China, local magazine LatePost reported in December.

The idea stemmed from “simple observations” of his family, said Hongsong CEO Li Qiao.

Li felt his mum had become “too idle” after retirement, spending much of her time just scrolling through social media or playing mahjong.

That stood in contrast to his grandparents, who engaged in activities such as calligraphy, painting and translating foreign books.

“The essential change was that her generation of retirees generally ‘played with phones’, but this purely entertainment-based way of killing time didn’t make her happy,” Li told LatePost.

At the same time, new challenges have also emerged from this digital shift, including being exposed to online scams, misinformation and the risk of digital addiction.

“(This marks) a profound transformation from being marginalised by the digital revolution to being active, though sometimes vulnerable, participants in it,” Shi said.

“A balanced approach is essential: stronger platform regulation and digital literacy programmes should complement offline community services, such as community centres for older adults, which can offer physical gatherings and structured activities for more holistic well-being.”