commentary Commentary

Commentary: Malaysian politics is going through a midlife crisis

It involves a contest of visions of what Malay supremacy should look like in multiracial Malaysia, says James Chin.

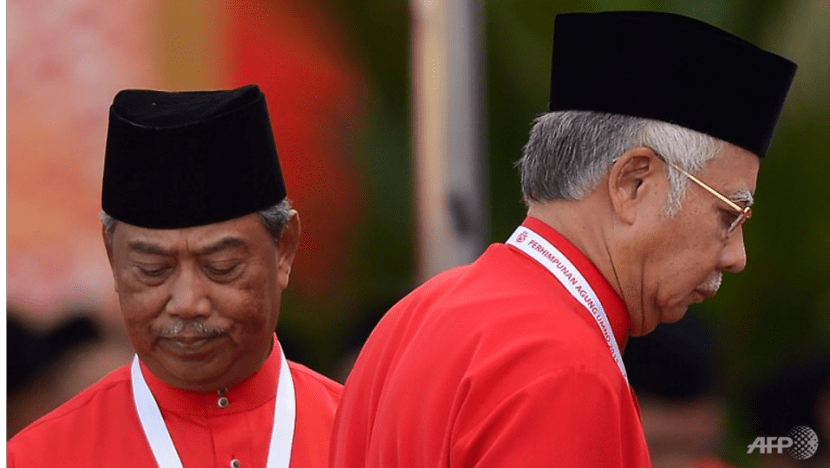

Composite picture of Hadi Awang, Muhyiddin Yassin and Zahid Hamidi. (Photos: Agencies)

HOBART: At the start of this year, I predicted a messy 2020 for Malaysian politics when calls for then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad to clarify his handing-over of the top job emerged.

But even I could not have imagined the subsequent upheaval, sparked by Dr Mahathir’s resignation which fuelled shocking defections and quiet backdoor bargaining, when the country found itself without government for a few weeks.

The dust has settled since, after Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin was sworn in in March, with COVID-19 providing a handy direction for the government agenda.

But beneath this focused paddling, a deeper re-examination and intensified politicking have been underway that may threaten to plunge the country into political chaos once more.

READ: Commentary: Muhyiddin Yassin, the all-seasoned politician, who rose to Malaysia’s pinnacle of power

READ: Commentary: What’s behind Mahathir’s sacking and Malaysia’s new political drama

THE SEARCH FOR A NEW MODEL

The thing is, ever since the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition fell, the new Muhyiddin Yassin government has been searching for a new political model to ensure the long-term political stability of the country.

The old Barisan Nasional (BN) model in place for 60 years, and even the PH model to some extent, is based on the same premise: There can only be one Malay party in a multiracial coalition.

When the BN was in power, UMNO was the first among equals. This allowed for multiple parties with different ideologies in the BN coalition to co-exist while ensuing UMNO, as the representative of the majority Malay race in Malaysia, had a trump card.

At its height, BN had 14 coalition parties including those opposed to the dominant Ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) ideology and a collection of small East Malaysian-based parties in Sabah and Sarawak.

But when it came to major decisions, UMNO had the “captain’s pick” or final call. UMNO alone decided what Malay nationalism, Malay identity and Islam meant.

Despite rejection from all non-Malay BN parties, UMNO went ahead to implement in 1983 a mandatory requirement for all students in public universities to pass a course on Tamadun Islam (Islamic civilisation) to obtain their degree.

UMNO may have been attacked from time to time by Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), even Bersatu when it was in the opposition. But by and large, but these challenges from fringe parties never posed a serious political threat.

READ: Commentary: Malay political unity in Malaysia is but a myth

READ: Commentary: Malaysia’s national consensus on race and politics risks unravelling

BUT THEN EVERYTHING CHANGED WHEN THE PAKATAN HARAPAN FELL

Muhyiddin’s Perikatan Nasional (PN) upset this balance of power when the PN government came into being with three major Malay parties - Bersatu, UMNO and PAS.

This essentially meant that while the Ketuanan Melayu ideology was overriding, there could be three different interpretations of what Malay nationalism, Malay identity and Islam translated into on policy matters on the economy, education and more.

It was clear Bersatu, UMNO and PAS differed on what these meant in terms of implementing a vision for the future of Malaysia.

To make matters worse, there was also confusion over the role of the old BN coalition and the new UMNO/PAS political pact - Muafakat Nasional.

UMNO insisted that the BN coalition was alive and refused to abandon its old non-Malay allies the Malaysian Chinese Association and the Malaysian Indian Congress.

There was controversy over whether these parties should be included as component parties in PN’s application to the Registrar of Societies in August.

There are murmurs within the new government that UMNO ultimately wants to swallow Bersatu, sideline PAS and eventually bring back BN as the basis for a future government. In other words, UMNO is plotting a return to the BN model.

READ: Commentary: Looks like regime change hasn’t altered the Malaysian psyche

READ: Commentary: This is not the end of Najib Razak

This thinking draws inspiration from the experience of the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan which has reinvented itself several times after spending a short stint in the opposition to storm back into power twice, in the 1990s and 2010s.

Bersatu, meanwhile, announced this month it will consider setting up a party wing for non-Malays. And a few days ago, Mr Muhyiddin strengthened the Muafakat Nasional’s position by emphasising Bersatu’s support for the coalition as a “frontline” working together in politics and government for integrity and trust.

Plenty of new challengers are waiting to pounce. Pejuang, a new party headed by Dr Mahathir, is going after UMNO and Bersatu.

Another party, a youth party, established by Syed Saddiq, the former Youth and Sports Minister seeks to court younger Malaysians. And of course there is Anwar Ibrahim’s Parti Kedilean Rakyat (PKR).

COMPETING VISIONS FOR MALAYSIA

The crux of the issue is this: Should the country return to the old model, the BN model which is essentially a multiracial coalition that upholds Malay supremacy, or a new modified model that is more progressive and inclusive?

There is no disagreement among Malay parties that Ketuanan Melayu should feature in that model.

But there is contention over the degree to which Islamic orthodoxy should be imposed and the role of non-Malays and non-Malay bumiputera.

Furthermore, Malaysia’s demographic changes and growing conservatism could reshape the political landscape, which can go two ways.

READ: Commentary: Was the Pakatan Harapan coalition doomed to fail from the start?

READ: Commentary: Malaysia succeeded in suppressing COVID-19 but here comes the harder part

In a first scenario, Malaysia moves right, similar to the paths taken by countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Islam become more prominent and the Islamic clergy are part of the political class. The political culture will be conservative and may see the waxing of influence by the Middle East. Non-Malays and non-Muslims are excluded from the political class in a systematic manner.

Second, Malaysia can follow its neighbour Indonesia and head towards a more plural political system.

In this scenario, while Malay nationalism will remain core, Malaysia will have a Malay-led political system where non-Malays and non-Muslims are accepted as part of the system.

This is where the youth party led by Syed Saddiq comes in. the thinking is that Malaysia youths are less prone to racial or identity politics because younger Malaysian Malays know it is not possible for non-Malays to challenge them politically based on simple demography.

By the end of this decade, Malay-Muslims will constitute just above 70 per cent of the population. In 30 years’ time, that figure is over 80 per cent.

FRAGILITY OF MALAY UNITY

While outsiders may see political developments in Malaysia as chaotic, I would argue we are seeing a major restructuring of Malay politics well overdue after 63 years of independence.

The February change of government this year has cemented a belief that the current Malay elites have rejected a more progressive and inclusive political system.

However, the fact that Malaysia is still facing political instability among the major Malay parties suggest that those who mounted the regime change did not expect Malay political unity to be so fragile.

They expected the new government, comprising the three important Malay parties - Bersatu, UMNO and PAS - to herald in a new era of Malay unity.

Unfortunately this did not happen. Instead, these developments have nursed a growing sentiment within the Malay community that both BN and PH models do not work, and that even the new PN model is not sufficiently robust to offer a long-term vision for Malaysia.

A MIDLIFE CRISIS

Since February this year, Malaysian politics has been a series of clashes inside the government on who sets the Malay agenda while on the outside, Dr Mahathir and other critics continue to attack what they call an illegitimate government.

These episodes underscore a far deeper crisis of the Malaysian polity that will not be easily resolved without some deeper soul-searching and public consensus building.

A short-term way out of the present crisis is the next general election.

GE15 is not due until 2023 but if infighting worsens, Muhyiddin may have no choice but to call one earlier - to temporarily settle the issue of which Malay party can provide the vision for a Malay-led Malaysia.

Professor James Chin is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania and Senior Fellow at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia.